CSA Consultation Paper 81-408 - Consultation on the Option of Discontinuing Embedded Commissions

CSA Consultation Paper 81-408 - Consultation on the Option of Discontinuing Embedded Commissions

CSA Consultation Paper 81-408

Consultation on the Option of Discontinuing Embedded Commissions

January 10, 2017

Administering the Canadian Securities Regulatory System

Les autorités qui réglementent le marché des valeurs mobilières au Canada

PART 1 -- INTRODUCTION

Background

On December 13, 2012, the Canadian Securities Administrators (the CSA or we) published CSA Discussion Paper and Request for Comment 81-407 -- Mutual Fund Fees (the Original Consultation Paper).{1} In that paper, we identified potential investor protection and market efficiency issues arising from the prevailing practice of remunerating dealers and their representatives for mutual fund sales through commissions, including sales and trailing commissions, paid by investment fund managers (embedded commissions). In particular, we identified how embedded commissions give rise to conflicts of interest that misalign the interests of investment fund managers, dealers and representatives with those of the investors they serve.

Since the publication of the Original Consultation Paper, the CSA completed roundtable consultations and discussion forums{2}, and commissioned independent research to further examine the identified investor protection and market efficiency issues.{3} After an extensive review of these inputs, in addition to our review of many other independent studies, we find that embedded commissions raise the following three key investor protection and market efficiency issues in Canada:

1. Embedded commissions raise conflicts of interest that misalign the interests of investment fund managers, dealers and representatives with those of investors;

2. Embedded commissions limit investor awareness, understanding and control of dealer compensation costs; and

3. Embedded commissions paid generally do not align with the services provided to investors.

The evidence we have gathered to date shows that embedded commissions encourage the sub-optimal behavior of fund market participants, including that of investment fund managers, dealers, representatives and fund investors, which reduces market efficiency and impairs investor outcomes. In particular, the data and research we reviewed suggests that embedded commissions can:

• incent investment fund managers to rely more on payments to dealers than on the generation of performance to gather and preserve assets under management; this incentive can in turn lead to underperformance and drive up retail prices for investment products due to a competition between investment fund managers to offer attractive commissions to secure distribution;

• incent dealers and their representatives to sell funds that compensate them the best or focus on only those funds that include an embedded commission rather than recommend a more suitable investment product; specifically, they can encourage a push for higher commission generating funds, such as higher-risk actively managed funds, which can impair investor outcomes;

• due to their embedded nature and complexity, inhibit the ability of investors to assess and manage the impact of dealer compensation costs on their investment returns; and

• cause investors to pay (indirectly through fund management fees) dealer compensation that may not reflect the level of advice and service they may actually receive; the cost of the advice and service provided may exceed its benefit to investors.

These issues and their causes appear to be driven by a compensation model with inherent conflicts of interest that research suggests are pervasive and are difficult to manage effectively. Based on the evidence we have gathered, we believe that a change to a different compensation model must be considered. Investors should be provided with a compensation model that empowers them and that better aligns the interests of investment fund managers, dealers and representatives with those of investors.

Consultation on direct pay arrangements

Before taking any regulatory action, and while we consider related regulatory initiatives underway, we want to consult with stakeholders on the potential option of discontinuing embedded commissions and transitioning to direct pay arrangements that:

• better align the interests of investment fund managers, dealers and representatives with those of investors;

• deliver greater clarity on the services provided and their costs; and

• empower investors by directly engaging them in the dealer and representative compensation process.

Direct pay arrangements could consist of various types of compensation arrangements including upfront commissions, flat fees, hourly fees, fees based on a percentage of assets under administration or other arrangements, provided in all cases:

i. the arrangement is negotiated and agreed to exclusively by the investor and the dealer, through the representative, pursuant to an explicit agreement; and

ii. the investor exclusively pays the dealer for the services provided under the agreement.

Under a direct pay model, we would expect dealers to offer their clients a compensation arrangement that suits their particular investment needs and objectives and the level of service desired. Investment fund managers could facilitate investors' direct payment of dealer compensation through payments taken from the investor's investment (for e.g. deductions from purchase amounts or periodic redemptions from the investor's account).

We recognize that such a change could have a profound effect on the fund industry and on investors in Canada, including potential unintended consequences. Therefore, a decision on whether to discontinue embedded commissions will only be reached after careful consideration and assessment of the possible impacts on investors and market participants and consultation with stakeholders. Accordingly, the aims of this consultation paper (Consultation Paper) are to obtain the requisite information the CSA needs to make an informed decision about discontinuing embedded commissions. Specifically, our objectives are to:

• assess the potential effects on investors and market participants of discontinuing embedded commissions, including on:

• the provision and accessibility of advice for Canadian investors, and

• business models and market structure, including the competitive landscape of the Canadian fund industry;

• if we decide to move forward, identify potential measures that could assist in mitigating any negative impacts of such a change; and

• obtain feedback on alternative options that could sufficiently manage or mitigate the identified investor protection and market efficiency issues.

We emphasize that we have not made a decision to discontinue embedded commissions. While we continue to consult and contemplate whether regulatory action should be taken to address the issues we have identified with the current commission-based compensation model, we encourage industry to create market-driven solutions and innovations that address the concerns we raise in this Consultation Paper, including adopting business models that:

• have at their core the interests of investors;

• align the benefits to the investment fund managers, dealers and representatives with the benefits to investors;

• make for more informed, engaged and empowered investors that expect and demand services that align with the fees they pay; and

• promote fair, competitive and efficient capital markets, and foster confidence in our market.

Impact analysis

This consultation will build on our previous consultations and the important body of research we have considered to date. We particularly seek from stakeholders analysis and perspectives that:

• were not raised in the prior consultations; and

• wherever possible, are evidence-based, data-centric and Canadian-focused.

The fund industry has to date provided research that finds that higher levels of wealth are achieved by advised investors over time, and maintains that embedded commissions are essential to delivering this benefit, particularly to investors with lower levels of wealth who may not otherwise be able to afford, or may not want to pay directly for, advice.

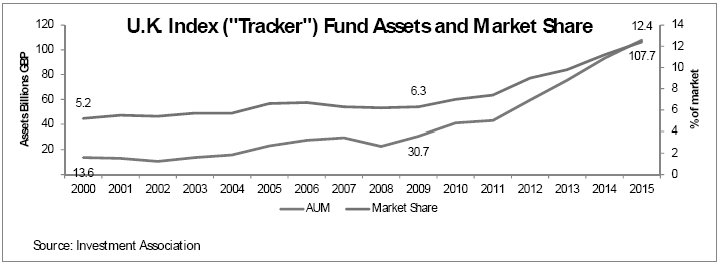

The fund industry has also pointed to the consequences of relevant regulatory reforms in other jurisdictions (such as the U.K. and Australia) as potential evidence of the likely impact of the discontinuation of embedded commissions in Canada. While observations about the impacts of relevant reforms in other jurisdictions are informative and insightful, we consider that the potential impacts from similar reforms in Canada might not be the same. The unique features of those foreign markets, including the characteristics of their respective market participants and the specific competitive dynamics within which they operate, their market structure, the savings habits of their local investors, as well as the scope of their respective reforms may all play a role in shaping the specific impacts.

The objective of this consultation is therefore to identify the potential effects of discontinuing embedded commissions in Canada based on what we know of our fund market and its participants, including our investment fund managers, our dealers, and the investors they currently serve. This objective includes understanding the potential impact such a change may have on the accessibility and affordability of advice for Canadian investors, including lower-wealth investors, and identifying ways to minimize this impact. Ultimately, our goal is to ensure that any regulatory action we may decide to take will provide a Canadian solution to challenges specific to the Canadian market, will result in more positive outcomes for Canadian investors and will minimize disruption for market participants. For this purpose, the contribution of the stakeholders to this consultation is very important.

Related regulatory initiatives and other alternatives

We are aware of the view of many fund industry participants that mutual fund fee reforms may be unnecessary in the wake of recent reforms aimed at improving investor awareness and understanding of fees and performance under the CSA's Point of Sale disclosure (POS) and Client Relationship Model Phase 2 (CRM2) projects, and the concept proposals to enhance the registrant-client relationship discussed in CSA Consultation Paper 33-404 Proposals to Enhance the Obligations of Advisers, Dealers, and Representatives Toward Their Clients (CSA CP 33-404). We also understand that industry participants are concerned by the number of current policy initiatives that affect their business and that require substantial changes in their operations and systems. Industry has urged us to allow full implementation of the POS and CRM2 reforms and fairly assess their results, and conclude consultations under CSA CP 33-404, before signaling that significant new reforms are needed.

We are of the view that the discontinuation of embedded commissions could be complementary to our recent reforms and proposals in that those existing and ongoing initiatives were not designed to, and may not fully address, the key investor protection and market efficiency issues we have identified in this Consultation Paper. In particular, we think that as long as dealer compensation remains embedded in the fund product, investment fund managers may continue to place greater emphasis on payments to dealers than on performance to gather and preserve assets under management. This compensation model may continue to encourage higher fund fees and impair investor outcomes and market efficiency, including effective competition in our market. We believe that discontinuing embedded commissions may address these issues by better aligning the interests of investment fund managers, dealers and representatives with those of investors. In this Consultation Paper, we seek your views on our assessment of the extent to which the discontinuation of embedded commissions may be required to address our key issues, including your views on whether recent disclosure reforms and proposals to enhance the registrant-client relationship may on their own sufficiently address our concerns.

We have also canvassed and thoughtfully considered a number of alternative options to address the investor protection and market efficiency issues we have identified. As more fully discussed in Appendix B of this Consultation Paper, we did not retain those other options as we found that they did not directly or fundamentally address the identified issues to the extent that discontinuing embedded commissions may.

Comment process

We welcome comments from investors, participants in the investment fund and financial services industries, and all other interested parties to the matters discussed in this Consultation Paper. Some CSA jurisdictions will hold in-person consultations in 2017 to facilitate additional feedback and further our consideration of the issues. Please see Part 7 of this Consultation Paper for information on how to submit comments. The comment period closes on June 9, 2017.

Structure of Consultation Paper

The remainder of this Consultation Paper is structured as follows:

• Part 2 discusses the key investor protection and market efficiency issues we have identified in connection with embedded commissions and highlights the evidence of these issues;

• Part 3 describes the potential scope of the discontinuation of embedded commissions if we were to proceed with rule-making;

• Part 4 sets out our assessment of the potential impacts of discontinuing embedded commissions on the Canadian fund market and specific stakeholders, including the potential impacts on market structure, business models and access to advice for Canadian investors, based on an analysis of data about Canadian fund investors and market participants;

• Part 5 explores measures that could mitigate the potential impacts and unintended consequences to investors and the Canadian fund market of discontinuing embedded commissions;

• Part 6 provides an overview of existing regulatory tools and related regulatory initiatives and our assessment of the extent to which these tools and initiatives may help address the key investor protection and market efficiency issues we have identified in connection with embedded commissions;

• Part 7 explains how stakeholders may provide comments and discusses next steps;

• Appendix A provides a detailed overview of the research that provides evidence of the key investor protection and market efficiency issues discussed in Part 2;

• Appendix B discusses other options we previously considered and the reasons why we did not retain them;

• Appendix C provides an overview of relevant reforms pertaining to dealer compensation in other jurisdictions; and

• Appendix D provides a list of the consultation questions.

PART 2 -- KEY INVESTOR PROTECTION AND MARKET EFFICIENCY ISSUES RAISED BY MUTUAL FUND FEES AND RELATED EVIDENCE

Further to the CSA's consultations on the Original Consultation Paper and our review of recent Canadian and other independent research on mutual fund fees as well as various other pieces of evidence, we have identified the following three main investor protection and market efficiency issues in connection with the mutual fund fee structure in Canada:

1. Embedded commissions raise conflicts of interest that misalign the interests of investment fund managers, dealers and representatives with those of investors;

2. Embedded commissions reduce investor awareness, understanding and control of dealer compensation costs; and

3. Embedded commissions paid generally do not align with the services provided to investors.

Below, we discuss each of the three issues in greater detail and reference various pieces of research and other data set out in Appendix A that evidence the issues.

We then consider the policy implications of the available evidence and the extent to which they suggest a need for change.

A. The issues and related evidence:

Issue 1: Embedded commissions raise conflicts of interest that misalign the interests of investment fund managers, dealers and representatives with those of investors

Based on the available evidence, the current embedded commission dealer compensation model appears to facilitate a mutually beneficial relationship between the investment fund managers who manufacture fund products and the dealers and representatives that distribute them. It aligns the investment fund manager's asset gathering and preservation objectives with the dealer's revenue maximization objectives. The evidence suggests that this alignment of commercial goals can alter the behavior of investment fund managers, and of the dealers and representatives who distribute the investment fund manager's products, in a way that is detrimental to market efficiency and investor outcomes. Specifically:

i. embedded commissions can reduce the investment fund manager's focus on fund performance, which can lead to underperformance;

ii. embedded commissions can encourage dealers and representatives to make biased investment recommendations which may negatively affect investor outcomes; and

iii. embedded commissions encourage high fund costs and inhibit competition by creating a barrier to entry.

i. Embedded commissions can reduce the investment fund manager's focus on fund performance, which can lead to underperformance

Investment fund managers who pay embedded commissions to dealers may be incented to rely more on those payments than on generating performance to attract and preserve assets under management. Consequently, the embedded commission structure may encourage investment fund managers to regard dealers and representatives, rather than their fund investors, as their "customers".{4}

The research that we have gathered and reviewed suggests that this inherent conflict of interest diminishes the investment fund manager's focus on risk-adjusted outperformance, thus impairing investor returns.

ii. Embedded commissions can encourage dealers and representatives to make biased investment recommendations which may negatively affect investor outcomes:

Dealers and representatives who are compensated through embedded commissions may be incented to make biased investment recommendations that give priority to maximizing compensation over the interests of the client. The research we have gathered and reviewed suggests that:

• compensation bias arising from embedded commissions can incent dealers and representatives to:

• recommend higher cost fund products that pay them higher embedded commissions than other suitable lower-cost and, possibly, better performing products, and

• promote the use of a particular purchase option{5}, such as the deferred sales charge (DSC) option{6}, that pays higher upfront embedded commissions, regardless of the availability of other purchase options that may better suit the investor's needs and objectives; and

• biased advice has an economically significant cost on investor outcomes.

iii. Embedded commissions encourage high fund costs and inhibit competition by creating a barrier to entry:

The research we have gathered and reviewed suggests that competition between investment fund managers to offer high embedded commissions to attract and secure distribution encourages and preserves high overall fund fees and discourages the manufacturing and sale of lower-cost alternatives, thus limiting price competition in Canada. This competition on the basis of commissions has a distorting effect on the allocation of capital by rewarding some investment fund managers more than is warranted, and others less than is warranted, while discouraging some from entering the market entirely.

Evidence:

In Appendix A, we provide evidence substantiating how the conflicts of interest inherent in embedded commissions alter the behavior of investment fund managers, dealers and representatives at the expense of market efficiency and investor interests.

Issue 2: Embedded commissions limit investor awareness, understanding and control of dealer compensation costs

Based on the available evidence, embedded commissions appear to limit investor awareness, understanding and control of dealer compensation costs. Specifically:

i. the lack of saliency of embedded commissions reduces investors' awareness of dealer compensation costs;

ii. embedded commissions add complexity to fund fees which inhibit investor understanding of such costs;

iii. the product embedded nature of dealer compensation restricts investors' ability to directly control that cost and its impact on investment outcomes.

i. The lack of saliency of embedded commissions reduces investors' awareness of dealer compensation costs:

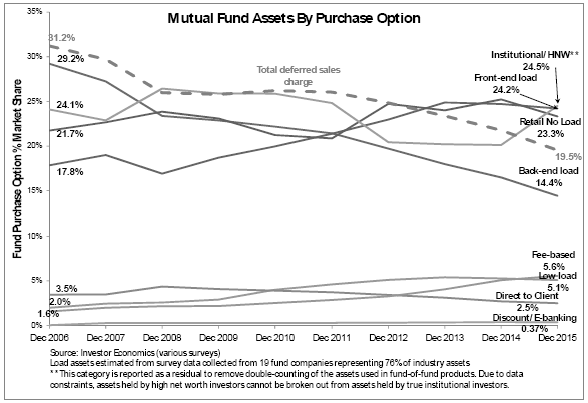

To facilitate the sale of funds, the Canadian fund industry has over the last several years gradually shifted away from transaction-based sales commissions paid directly by investors toward a greater reliance by both investment fund managers and dealers on product embedded commissions. For example, in 1996, trailing commissions accounted for slightly more than one quarter of a typical representative's book of business; by 2011, that share had grown to an estimated 64%.{7}

This move away from transaction-based sales commissions has reduced the saliency of dealer compensation costs for investors and, accordingly, reduced their sensitivity to such costs. The research we have gathered and reviewed is clear that the majority of Canadian fund investors are not aware of what they pay for financial advice or that they pay for financial advice at all.{8} Consequently, these costs do not figure into their decision-making. The research we have gathered and reviewed suggests that investors are more sensitive to salient upfront fees like front-end loads and are more likely to control such visible and salient fees that they must pay directly.

ii. Embedded commissions add complexity to fund fees which inhibit investor understanding of such costs:

Further contributing to investors' limited awareness and understanding of fund fees, including embedded commissions, is the complexity of fund fees in terms of structure and options on offer. Although all dealer compensation costs that fund investors pay directly (such as sales charges) and indirectly through ongoing fund fees (such as trailing commissions) are disclosed in the fund's prospectus, the fund facts document and the annual report on charges and other compensation, the variance in such fees between investment fund managers, fund types (i.e. asset classes), fund series and purchase options can overwhelm investors' capacity to understand the specific fund fees, including dealer compensation costs, that apply to their investment.

The complexity of the mutual fund fee structure can make it challenging for all but sophisticated investors to measure the value of the services they receive against the costs they pay and assess the impact of fees on their investment returns.

The research we have gathered and reviewed suggests that price complexity in retail financial products increases the information asymmetry between investors and product manufacturers and distributors, which increases investors' reliance on more informed intermediaries for their investment choices and decisions.

iii. The product embedded nature of dealer compensation restricts investors' ability to directly control that cost and its effect on investment outcomes:

Since the cost of dealer compensation is embedded in the fund's ongoing management fees, investors have no ability to directly negotiate this cost and consequently have no control over the amount they ultimately pay their dealer and their representative. The only control investors have on dealer compensation costs under the embedded commission model is to vote on a proposed increase to fund management fees (from which dealer compensation is paid).{9}

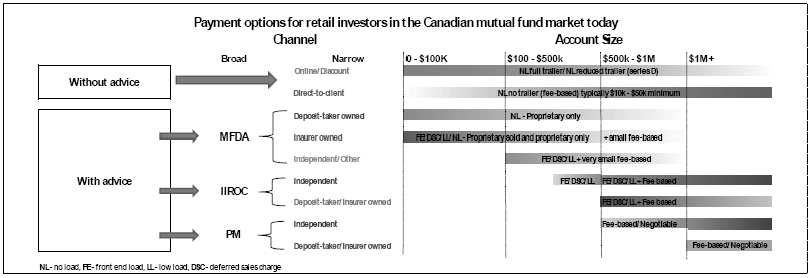

Opportunities for retail investors in Canada to reduce the trailing commissions they indirectly pay or avoid them altogether are very limited. As a result, investors who may desire little or no advice (e.g. do-it-yourself investors) may often bear the cost of full unreduced trailing commissions. And investors who do desire advisory services but who wish to pay for them directly rather than through embedded commissions similarly have limited options because direct pay arrangements are typically available only through dealers servicing higher net worth investors. We note that even though the vast majority of investment fund managers now offer fee-for-service series (e.g. Series F) for minimal investments, the distribution of such series is still limited in comparison to the distribution of series with embedded commissions due to the fee-based account minimums imposed by the dealer.{10}

Furthermore, because trailing commissions are deducted at the fund level rather than the account level, some investors indirectly subsidize certain dealer compensation costs that are not attributable to their investment in the fund, which means they indirectly pay excess fees. This situation is called "cross-subsidization". For example, front-end load investors in a fund may cross-subsidize the costs attributable to DSC investors.{11} Opportunities for cross-subsidization would be reduced if each investor were charged a fee covering his/her own distribution costs at the account level, which would enable each investor to pay only for his/her costs and thus have greater control over such costs.

Investors' inability to make an informed choice based on fund costs, including dealer compensation, and to control such costs due to their product-embedded nature can lead to sub-optimal investment choices and outcomes.

Evidence:

At Appendix A, we provide evidence that:

• the lack of saliency and the complexity of fund fees, including embedded commissions, impacts investors' awareness and understanding of such fees and accordingly reduces the significance of fund fees as a factor in investor decision-making; and

• the product embedded nature of dealer compensation restricts investors' ability to directly control that cost and its impact on investment outcomes; this evidence includes an overview of:

• the cross-subsidization that results from dealer compensation charged at the fund level, and

• the limited options investors currently have in Canada to limit or avoid the payment of embedded commissions.

Issue 3: Embedded commissions paid generally do not align with the services provided to investors

There is generally no clear relationship between the level of embedded commissions set and paid by the investment fund manager to the dealer and the level of services and advice the dealer and the representative provide to investors in exchange for such compensation. Specifically:

i. investors do not receive ongoing advice commensurate with the ongoing trailing commissions paid; and

ii. the cost of advice provided through commissions may exceed its benefit to investors.

i. Investors do not receive ongoing advice commensurate with the ongoing trailing commissions paid:

As mentioned above, trailing commission rates may vary between investment fund managers, fund types, fund series and purchase options. They may also in some cases vary over the course of the investment.{12} While a reasonable assumption might be that the rate of the trailing commission is reflective of the level of service an investor receives from a dealer and their representative (i.e. the greater the rate, the greater the service), current practice suggests that no such relationship exists between the fees paid and the services provided in exchange.

Embedded commissions are paid to dealers regardless of the extent of the services that a representative provides to the investor in connection with an investment in a fund. The same compensation is paid irrespective of whether the representative provides only transaction-oriented advice or provides a broader range of ongoing investment services and financial advice that is tailored to the investor's specific needs. For example, our review of the Canadian fund market finds that higher than average trailing commissions are sometimes paid on investment funds offering pre-packaged investment solutions (i.e. funds-of-funds) that relieve the representative from having to do much of the fund selection and asset allocation they might otherwise have to do for a client. Similarly, discount brokers who provide execution-only services often distribute fund series that pay them the same trailing commission that would be paid to a full service dealer.

The 'one-size-fits-all' nature of the trailing commission payment therefore seems misaligned with the provision of services and advice customized to the investor's specific needs, expectations and preferences. A contributing factor to this misalignment is likely investors' low awareness and understanding of fees including dealer compensation (as discussed under Issue 2 above), which causes investors to not demand a level of service and advice commensurate with the fees they have indirectly paid for.

Absent a clear relationship between the rate of the embedded compensation paid to the dealer and their representative and the level of services an investor receives in return, the payment of embedded compensation may be perceived to be tied to the simple distribution of the fund product as opposed to the provision of ongoing advice and services. Certain industry submissions received in response to our Original Consultation Paper would seem to confirm this view as several commenters indicated that trailing commission payments support dealer operations and sales activity more than the provision of ongoing advice.

If investors are getting basic one-time services centered on the trade as opposed to ongoing advice and services in exchange for the ongoing embedded commissions paid out of their funds' management fees, they may be indirectly paying too much for the services they are actually receiving. Moreover, since the aggregate amount of embedded commissions that investors pay increases as their holding period increases, those investors who remain invested longer may pay more fees than others for the same basic service.

ii. The cost of advice provided through embedded commissions may exceed its benefit to investors:

Some of the research we reviewed suggests that investors may derive no measurable net benefit from financial advice paid for through embedded commissions and may in some cases be worse off because of it. Certain research finds that the advice of representatives may be skewed not only by compensation biases, but may also be affected by representatives' varying skills and knowledge about investing which in some cases may benefit from increased proficiency requirements. Other research suggests that the benefits that investors derive from the advice of representatives may be largely behavioral and thus intangible in nature, such as the development of good savings discipline, overcoming inertia, the reduction of anxiety, and the creation of trust.

Evidence:

In Appendix A, we provide evidence that:

• investors do not receive ongoing advice commensurate with the ongoing trailing commissions paid; and

• the cost of advice provided through embedded commissions may exceed its benefit to investors.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Questions

1. Do you agree with the issues described in this Part? Why or why not?

2. Are there other significant issues or harms related to embedded commissions? Please provide data to support your argument where possible.

3. Are there significant benefits to embedded commissions such as access to advice, efficiency and cost effectiveness of business models, and heightened competition that may outweigh the issues or harms of embedded commissions in some or all circumstances? Please provide data to support your argument where possible.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

B. Policy implications:

The foregoing shows that product embedded commissions affect the behavior of fund market participants in a way that undermines investor protection and the fairness and efficiency of our capital markets as well as confidence in our market. This situation suggests a need to consider regulatory action.

To address the investor protection and market efficiency issues outlined in this Consultation Paper, the CSA considered and discussed the range of policy options set out in the chart below:

Potential regulatory options

1. Use existing tools

2. Enhancements to disclosure

3. Investment fund manager focused initiatives

4. Enhance-ments to registrant-client relation-ship

5. Mutual fund fee reforms

Roll out POS and CRM2 and monitor impact

Conduct NI 81-105 mutual fund sales practices reviews

CRM2 cost reporting / performance reporting benchmarking

Better fee disclosure in fund facts (giving more context for fund costs)

Require separate series for each purchase option

Make distribution costs an expense of the fund

Require DIY discount series

Consider extent to which concept proposals under CSA CP 33-404, if implemented, may respond to fund fee issues

Cap all forms of embedded compensation to a maximum limit

Discontinue all forms of embedded compensation

CSA regulatory project focus

Regulatory options not retained

Guiding considerations for evaluation of options:

Our evaluation of the range of options and determination of which options should be retained and which ones should not were guided by the extent to which an option directly addresses the three investor protection and market efficiency issues we identified. We specifically considered the questions below:

a. How many problems does the option address and to what degree?

b. Would the impact be direct/immediate rather than indirect/over time?

c. What is our level of uncertainty regarding the impacts/what is our expectation regarding unintended consequences?

d. Does it simplify or add to the complexity of the fund fee structure?

e. Does it enhance competition in our market and market efficiency generally?

Where we determined that an option would potentially address one issue to some degree, but at the same time would fail to address or would likely exacerbate another issue, or would potentially increase the complexity of fund fees or fail to enhance competition in the market, we opted to not retain the option.

When we evaluated the options through this lens, our analysis drew us to not retain the options highlighted in red and retain the options highlighted in green in the table above.

The options we opted to not retain and the reasons why are described in Appendix B of this Consultation Paper.

The options we retained include:

i. maintain and use our existing tools, namely enhanced transparency of fund fees under POS and CRM2, and review of sales incentives under NI 81-105 Mutual Fund Sales Practices (NI 81-105);

ii. continue to explore concept proposals under CSA CP 33-404 to strengthen the obligations of dealers and their representative towards their clients; and

iii. discontinue embedded commissions and transition to direct pay arrangements.

Following a thorough evaluation, we believe that options "i" and "ii" may provide only a partial resolution to the issues identified in this Consultation Paper and that option "iii" may need to be considered in conjunction with options "i" and "ii" to achieve the desired outcomes. We accordingly view option "iii" as being complementary to options "i" and "ii".

In Part 6 of this Consultation Paper, we provide our detailed assessment of the extent to which the above key issues may be addressed by existing CSA regulation and ongoing proposals, and seek your views on that assessment.

PART 3 -- OVERVIEW OF THE PROPOSED OPTION TO DISCONTINUE EMBEDDED COMPENSATION

In this part, we discuss the potential scope of the discontinuation of embedded commissions should the CSA decide to move forward with rule-making. In particular, we consider:

• what types of securities would be affected, and

• what types of payments would be discontinued.

1. Types of securities affected

NI 81-105, implemented in 1998, governs the payments that investment fund managers may make to dealers in connection with the distribution of securities of a mutual fund.{13} While that rule currently applies only to mutual funds that are reporting issuers, we recognize that its regulatory objectives have equal application to the distribution of other investment funds and comparable investment products that we regulate.{14}

Over the last few years, the CSA have made regulatory changes to ensure a consistent regulatory framework in key areas for all types of retail investment funds, regardless of whether structured as a mutual fund, an exchange-traded mutual fund (ETF) or a non-redeemable investment fund.{15} We have also recognized the growth of structured notes{16} as a retail investment product and communicated our intention to regulate them in a similar manner to investment funds, where appropriate.{17}

While investment funds and structured notes sold in the exempt market have to date generally not been subject to the same requirements as retail investment funds, we consider that the investor protection and market efficiency issues that stem from embedded commissions, as evidenced under Part 2, require consistent treatment both in the prospectus-qualified and prospectus-exempt markets. To do otherwise would create an opportunity for regulatory arbitrage.{18}

Recognizing that the fee structure of various types of investment funds and structured notes commonly includes embedded commissions, and with the aim of promoting a level playing field amongst comparable investment products and limiting opportunities for regulatory arbitrage, we currently anticipate that any regulatory proposal to discontinue embedded commissions would affect:

• an "investment fund"{19}, as defined under securities legislation and

• structured notes,

whether sold under a prospectus or in the exempt market under a prospectus exemption.

Although investment fund-like products, such as segregated funds, are not within the purview of securities legislation and therefore would not be captured in any CSA rule proposal to discontinue embedded commissions, we recognize the importance of a harmonized approach to regulating such products given their similarity to investment fund products, including their payment of product embedded commissions to intermediaries. The CSA will accordingly continue to liaise with insurance regulators to address the potential risk of regulatory arbitrage between investment funds and individual segregated funds.

In the interest of achieving a harmonized approach, the Canadian Council of Insurance Regulators (CCIR) established a Segregated Funds Working Group in 2015, with a mandate to, among other things, identify potential gaps in the comparative regulatory frameworks for segregated funds and mutual funds and assess the potential risk of regulatory arbitrage by dually-licensed (insurance and mutual funds) insurance agents. In their May 2016 issue paper calling for input on how to address key gaps between the regulations pertaining to mutual funds and segregated funds{20}, the CCIR indicates that although it is currently not aware of any statistical evidence to demonstrate that regulatory arbitrage is occurring between mutual funds and segregated funds, it will act proactively to amend regulation where appropriate to ensure that intermediaries have little incentive to prioritize their own interests over those of clients. The issue paper identifies the CSA's consultation on how to address the potential investor protection and market efficiency issues arising from embedded commissions as an issue of particular relevance, and the CCIR will review the CSA policy direction on this matter and assess its appropriateness for segregated funds.{21}

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Questions

4. For each of the following investment products, whether sold under a prospectus or in the exempt market under a prospectus exemption:

• mutual fund

• non-redeemable investment fund

• structured note

should the product be subject to the discontinuation of embedded commissions? If not:

a. What would be the policy rationale for excluding it?

b. What would be the risk of regulatory arbitrage occurring in the exempt market if embedded commissions were discontinued for the product only when sold under prospectus?

5. Are there specific types of mutual funds, non-redeemable investment funds or structured notes that should not be subject to the discontinuation of embedded commissions? Why?

6. Are there other types of investment products that should be subject to the discontinuation of embedded commissions? Why?

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

2. Types of payments discontinued

NI 81-105 currently prohibits mutual funds that are reporting issuers and members of the organization of such mutual funds from making payments to dealers or their representatives in connection with the distribution of securities of a mutual fund. The rule however excepts from this prohibition the payment of commissions (including trailing commissions) and the provision of support to dealers for marketing and educational practices by members of the organization of mutual funds.

If the CSA were to move forward with a rule proposal, we currently anticipate that we would seek to discontinue any payment of money to dealers in connection with an investor's purchase or continued ownership of a security described above that is made directly or indirectly by any person or company other than the investor. The rule would preclude compensation to dealers that is paid or funded by the investment fund or the investment fund manager or structured note issuer out of fund assets or revenue.

We anticipate this change would at a minimum prohibit the payment by investment funds, investment fund managers or structured note issuers to dealers of the following embedded commissions:

• ongoing trailing commissions or service fees; and

• upfront sales commissions for purchases made under the DSC option.

To be clear, the discontinuation of embedded commissions would enable dealers and their representatives to adopt various types of compensation arrangements. Under direct pay arrangements, dealers and their representatives could opt to be compensated through upfront commissions (such as front-end sales loads), hourly fees, a flat fee, a fee based on a percentage of the client's assets under administration (fee-based arrangement), or other suitable compensation arrangement, provided in all cases:

a. the method and the rate of the representative's compensation in connection with the purchase of a security and other services provided to the investor are negotiated and agreed to exclusively by the investor and the dealer, through the representative, pursuant to an explicit agreement; and

b. the investor exclusively pays the dealer for the services provided under the agreement.

Under direct pay arrangements, we would expect dealers and representatives to offer their clients a compensation arrangement that suits their particular investment needs and objectives and reflects the level of service desired. For example, ongoing fees should be charged for ongoing services.

We believe that the above terms mitigate the close alignment of interests between investment fund managers, dealers and representatives.

While investment funds, investment fund managers and structured note issuers would no longer be allowed to pay or fund compensation to dealers from their own assets or revenue in connection with an investor's purchase or continued ownership of a security, we anticipate allowing them to facilitate the investor's payment of dealer compensation. Specifically, the investment fund manager would be permitted to collect the dealer's compensation, either through deductions from purchase amounts or through periodic withdrawals or redemptions from the investor's account, and remit it to the dealer on the investor's behalf, provided the investor consents to this method of payment.

At this time, we anticipate that we would permit the following types of dealer compensation payments:

• referral fees paid for the referral of a client to or from a registrant;{22}

• dealer commissions paid out of underwriting commissions on the distribution of securities of an investment fund or structured note that is not in continuous distribution under an initial public offering;

• payments of money or the provision of non-monetary benefits by investment fund managers to dealers and representatives in connection with marketing and educational practices under Part 5 of NI 81-105;{23} and

• internal transfer payments{24} from affiliates to dealers within integrated financial service providers{25} which are not directly tied to an investor's purchase or continued ownership of an investment fund security or structured note.

We acknowledge that the above types of payments may give rise to conflicts of interest that may continue to incent registrant behavior that does not favour investor interests. We therefore seek your responses to the questions below.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Questions

7. Do you agree with the discontinuation of all payments made by persons or companies other than the investor in connection with the purchase or continued ownership of an investment fund security or structured note? Why or why not?

8. Are there other fees or payments that we should consider discontinuing in connection with the purchase or continued ownership of an investment fund security or structured note, including:

a. the payment of money and the provision of non-monetary benefits by investment fund managers to dealers and representatives in connection with marketing and educational practices under Part 5 of NI 81-105;

b. referral fees; and

c. underwriting commissions.

Why? What is the risk and magnitude of regulatory arbitrage through these types of fees and commissions?

9. If payments and non-monetary benefits to dealers and representatives for marketing and educational practices under Part 5 of NI 81-105 are maintained further to the discontinuation of embedded commissions, should we change the scope of those payments and benefits in any way? If so, why?

10. With respect to internal transfer payments:

a. How effective is NI 81-105 in regulating payments within integrated financial service providers such that there is a level playing field for proprietary funds and third party funds?

b. Should internal transfer payments to dealers within integrated financial service providers that are tied to an investor's purchase or continued ownership of an investment fund security or structured note be discontinued? Why or why not? To what extent do integrated financial service providers directly or indirectly provide internal transfer payments to their affiliated dealers and their representatives to incent the distribution of their products?

c. Are there types of internal transfer payments that are not tied to an investor's purchase or continued ownership of an investment fund security or structured note that should be discontinued?

11. If we were to discontinue embedded commissions, please comment on whether we should allow investment fund managers or structured note issuers to facilitate investors' payment of dealer compensation by collecting it from the investor's investment and remitting it to the dealer on the investor's behalf.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

PART 4 -- REGULATORY IMPACT

The purpose of this part is to outline our assessment of the possible market impacts of discontinuing embedded commissions. In particular, we assess the potential impacts this change could have on the Canadian investment fund sector, including on market structures, business models and on the accessibility and scope of advice provided to retail investors, based on data we have gathered and the conclusions we have drawn from this data.

The regulatory impact part is divided into four sections. In section one, we provide a number of important facts about Canadian households, the fund market and the distribution of funds and securities in general that will help us anticipate possible market impacts of discontinuing embedded commissions. In section two, we outline possible overall or high-level impacts on the market in the event of the discontinuation of embedded commissions. This section is followed, in section three, by a more narrow focus on the impacts to specific stakeholders. Finally, in section four, we conclude by outlining how the discontinuation of embedded commissions may address the key issues outlined previously in Part 2 of this Consultation Paper. We look to all stakeholders to provide feedback and data responding to the conclusions that we draw here.

1. Important facts about the fund market and fund market participants today

A prerequisite for the CSA's assessment of possible policy options regarding fund fees was to understand and analyze what we know about the market today and in particular, what we know about the respective market participants -- advised and non-advised fund investors, consumers of financial services generally, access to advice by retail investors, investment fund distribution channels and investment fund managers.

We provide pertinent information for each of these groups below using data from Investor Economics, Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada (IIROC), Mutual Fund Dealers Association (MFDA), Morningstar Direct and the Ipsos Canadian Financial Monitor survey.{26}

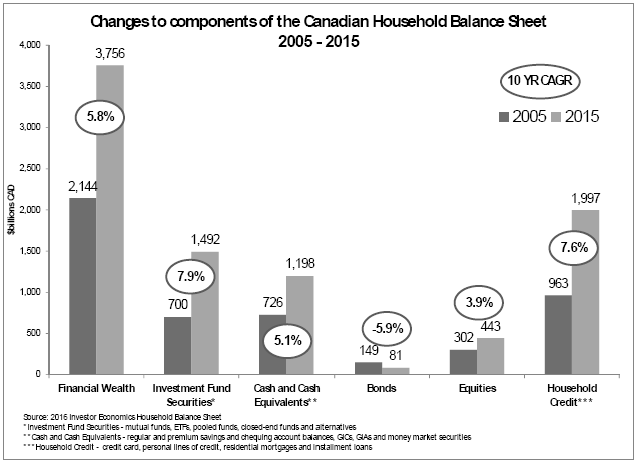

a. Canadian Households

At the end of 2015, financial wealth of Canadian households reached $3.8 trillion dollars, increasing an average 5.8% per year since 2005. In comparison, household credit (due primarily to the increase in residential mortgages) grew 7.6% over the same period reaching just under $2 trillion dollars at the end of 2015. In aggregate, and as widely reported elsewhere,{27} Canadian households have become more leveraged over the last 10 years.

Within the asset side of the balance sheet, Canadian households, in aggregate,{28} had a significant and growing share of their total financial wealth in funds and cash and cash equivalents. At the end of 2015, Canadian households held $1.5 trillion or 40% of their aggregate financial wealth in investment fund securities and $1.2 trillion or 32% of aggregate wealth in cash and cash equivalents{29}. In comparison, directly held securities (stocks and bonds) made up only $524 billion or 14% of aggregate financial wealth. Total assets held in bonds in particular declined over the last 10 years while assets held in equities saw relatively modest growth.

While both investment fund securities and cash and cash equivalents made up a significant portion of aggregate household financial wealth at the end of 2015, assets within investment funds have grown faster since 2005. On average, investment fund assets increased by 7.9% per year over the last ten years compared to 5.1% for cash and cash equivalents.

Figure 1: The Canadian household balance sheet in aggregate

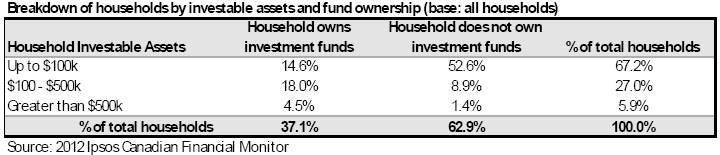

We turn now to the distribution of assets and investment fund ownership across households by analyzing the data from the 2012 Ipsos Canadian Financial Monitor.{30}

The majority of Canadian households have investable assets below $100,000

Table 1: Household distribution by investment fund ownership and investable asset band

The first important fact with respect to Canadian households is that the majority of households that save have investable assets of $100,000 or less. At the end of 2012, 67% of households had investable assets{31} of $100,000 or less (mass-market households), 27% had investable assets of between $100,000 and $500,000 (mid-market households) and 6% of households had investable assets of $500,000 or more (affluent households).

The majority of Canadian households do not own investment funds

The second relevant fact is that the majority of Canadian households do not own investment funds. At the end of 2012, 37% of Canadian households held investment funds{32} while the balance did not.

Mass-market households make up the largest share of those that do not own investment funds

Table 2: Household distribution by investment fund ownership

By far, the majority of households that do not hold investment funds (84%) are those with investable assets of $100,000 or less.

However, among investment fund owning households, the majority have relatively modest to moderate levels of accumulated financial wealth

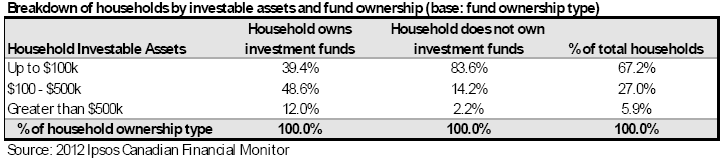

Yet, like their share of Canadian households generally, mass-market and mid-market households made up the largest share of households that own investment funds.

At 2012, 39% of all households that owned investment funds were mass-market households, 49% were mid-market households, and the remaining 12% of fund owning households were affluent households.

Investment funds, like most securities, are more frequently owned by households with higher levels of accumulated financial wealth

The distribution of fund ownership, like the distribution of financial wealth generally, skews toward households with higher levels of investable assets.{33} Mass-market households appear underrepresented relative to their share of total households (i.e. only 39% of those households own funds despite comprising 67% of all households), while the opposite appears true for mid-market and affluent households. Investment funds, like most securities, tend to be a higher-wealth product.

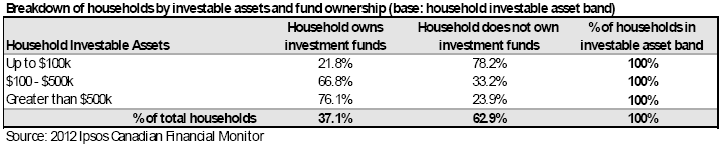

Investment funds are less popular than traditional savings vehicles with mass-market households

Table 3: Household distribution by investable asset band

We can see this lack of relative popularity more clearly when we look at the proportion of investment fund ownership across investable asset bands. Table 3 above provides the breakdown of the Canadian households that own investment funds (i.e. 37% of all households).

At the end of 2012, only 22% of mass-market households held investment funds. These households will typically hold more conservative financial products instead, such as cash, GICs etc. For mid-market and affluent households, the majority held investment funds at the end of 2012. 67% of mid-market households held investment funds and 76% of affluent households held investment funds at the end of 2012. Once again, investment fund ownership is less prevalent for households with modest levels of savings relative to households with higher levels of accumulated wealth.

Investment fund owning households with lower levels of accumulated wealth are less likely to state that they use advice

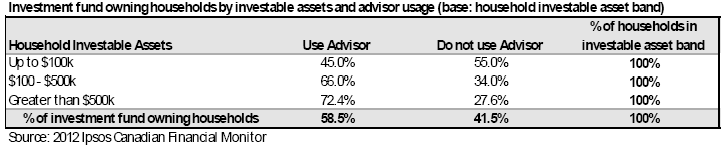

Table 4: Fund owning household distribution by investable asset band

Table 4 above provides a breakdown of the households that own investment funds (i.e. the subset of 37% of all households) and their use of an advisor{34}.

As Table 4 highlights, the data suggests that advice usage tends to be more of a higher-wealth product. Its prevalence among investment fund owning households rises with the level of investable assets. At the end of 2012, only 45% of investment fund owning mass-market households stated that they used an advisor{35} while the majority of investment fund owning mid-market (66%) and affluent households (72%) used an advisor.

b. Investment Fund Distribution

Whether advised or not, households must purchase their investment funds through a dealer. A key piece of information needed in order to anticipate the possible market impact of the discontinuation of embedded commissions is an understanding of where investors access investment funds today. We will look at this question from a number of different angles and data sources, starting with the Ipsos Canadian Financial Monitor data.

In the tables below, we have grouped fund distribution by the following firm types:

• deposit-taker owned{36} fund distributors;

• insurer owned{37} fund distributors;

• independent{38} fund distributors; and

• other integrated{39} fund distributors.

In each of the tables, we take a closer look at where households that hold investment funds accessed their funds. Households may have multiple relationships with different types of fund distributors (e.g. a household may work with a deposit-taker and an insurer or a deposit-taker and an independent or just a deposit-taker etc.). We have cross-tabbed fund distributor types by grouping deposit-takers and insurers (the traditional integrated financial product distributors) together and independents and other distributors (the group traditionally labeled as independent fund dealers) together.

Note that households that have not purchased their funds through a deposit-taker/insurer or through an independent/other dealer have purchased their funds through an association{40} or have not identified where they purchased their funds.

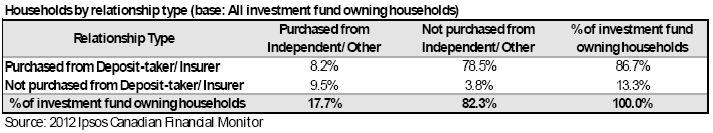

Most households purchase their funds through a deposit-taker or insurer owned dealer

Table 5: Fund owning household distribution by fund dealer relationship

Deposit-taker and insurer owned fund dealers dominate fund distribution in Canada. At the end of 2012, of the 37% of households that owned investment funds, 87% purchased their funds through a deposit-taker/insurer owned distributor while only 18% purchased their funds through an independent/other fund distributor (a small percentage of households purchased their funds from both dealer groups).

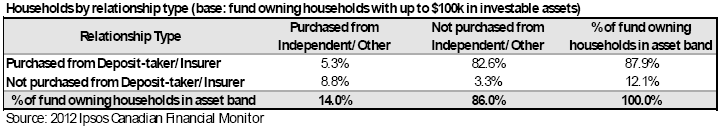

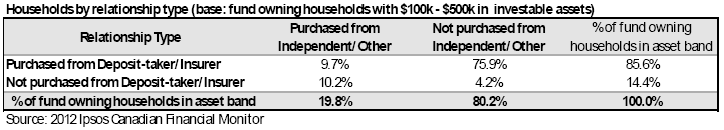

Households with lower levels of accumulated wealth are less likely to purchase their funds through an independent dealer

Table 6: Mass-market household distribution by fund dealer relationship

Table 7: Mid-market household distribution by fund dealer relationship

Table 8: Affluent household distribution by fund dealer relationship

Mass-market households are less likely to purchase their funds through an independent/other fund distributor. At the end of 2012, only 14% of mass-market households purchased their funds through an independent/other fund distributor compared to 18% of households overall and 21% of affluent households. Mass-market households were also much more likely to be solely purchasing their funds through a deposit-taker/insurer owned dealer (i.e. 83%) than were households with higher levels of investable assets (i.e. 76% and 75% respectively for mid-market and affluent households).

Fund distributors owned by deposit-takers and life insurers dominate investment fund distribution

Across all levels of investable assets, deposit-taker and insurer owned fund distributors tended to dominate fund distribution. The majority of households were working with a deposit-taker/insurer for at least one of their investment fund holdings (i.e. 88% for mass-market, 86% for mid-market and 87% for affluent households). Usage of deposit-taker/insurer fund distributors did not fall below 86% of households for all household types and for the industry as a whole. The data suggests that Independent/Other fund distributors tend to have a relatively small footprint in the market today.

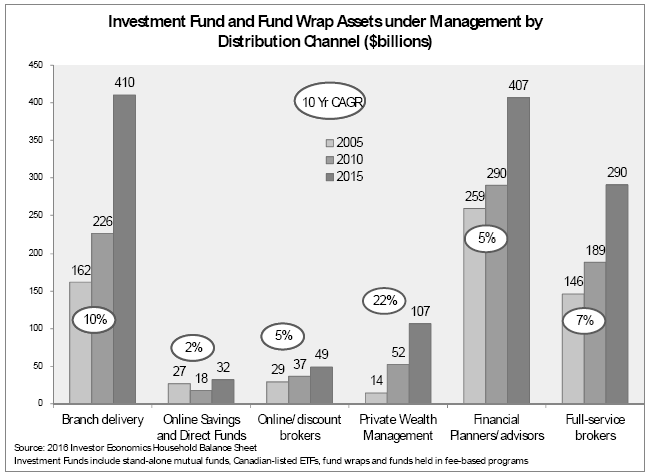

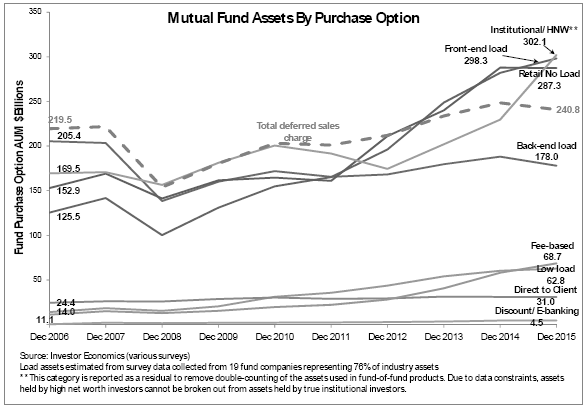

These insights are also confirmed by data from Investor Economics.{41} In the two graphs below, we show investment fund and fund wrap assets, their 10 year compound average growth rates (CAGR) and market share for Investor Economics' six distribution categories -- branch delivery, online savings and direct funds, online/discount brokers, private wealth management, financial planners/advisors and full-service brokers. We also highlight the change in market share for deposit-taker and insurer owned fund distributors in each channel.

Deposit-taker and insurer owned fund dealers dominate investment fund distribution today

Figure 2: Investment fund assets by distribution channel

As is shown in Figure 2 above, the majority of fund assets reside in the branch delivery channel and the financial planner/advisor channel.

The branch delivery channel saw the second highest rate of fund asset growth over the last ten years (10%) after the private wealth channel (22%). This growth rate is particularly impressive given the size of the branch delivery channel 10 years ago.

The financial planner/advisor channel{42}, which had possessed the largest share of investment fund assets ten years ago, was still the second most important distribution channel at the end of 2015 but had grown much slower than all but the online savings and direct funds and the online/discount brokerage channels. Investment fund asset growth in the financial planner/advisor channel was also slower (5%) than in the full-service brokerage channel over the period (7%). Growth of investment fund assets in the full-service broker channel in particular was driven by a number of factors including the growth in fee-based account usage and in the share of investment funds used in these accounts.{43}

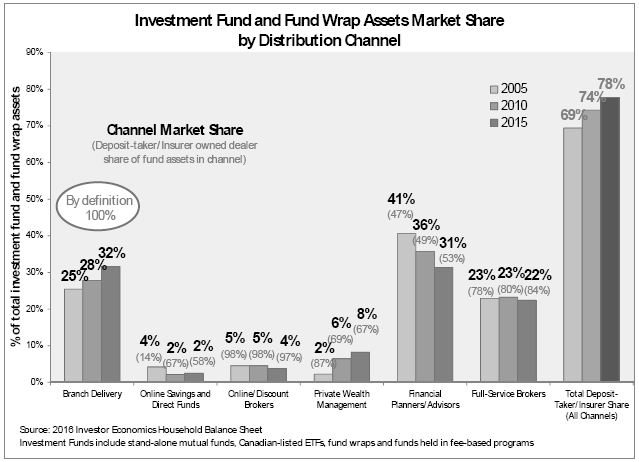

Figure 3: Investment fund assets market share by distribution channel and dealer type

The relative growth of investment fund assets in the financial planner/advisor channel is noteworthy because this is where the majority of independent mutual fund dealers are captured. As shown in Figure 3 above, at the end of 2015, the financial planner/advisor channel was the only channel where the deposit-taker/insurer share of investment fund assets was below 55%. Although, even in that channel, there has been an increase in deposit-taker and insurer ownership over the last ten years, increasing from 47% to 53% of investment fund assets in the channel.

As also highlighted in Figure 3, the branch delivery and full-service brokerage channels which had the second and third highest average annual growth over the last ten years, also had significant deposit-taker and insurer ownership at the end of 2015 (the former category is by definition 100% deposit-taker owned distribution).

At the end of 2015, the branch delivery channel held 32% of total investment fund assets, up from 25% ten years earlier. Much of that growth in market share came at the expense of the financial planner/advisor channel which saw its share of market decline from 41% to 31% over the period. The full-service broker channel saw its investment fund market share remain essentially constant while deposit-taker and insurer owned share of that channel increased from 78% to 84%. In total, at the end of 2015, deposit-taker and insurer owned dealers administered 78% of the investment fund and fund wrap assets held by Canadian households, up from 69% ten years earlier. In dollars, investment fund assets held through deposit-taker and insurer owned dealers, across all channels, increased from $443 billion in 2005 to $1 trillion at the end of 2015.

Next, we turn to data from the MFDA and IIROC in order get a sense of whether or not the insights from the Investor Economics and Ipsos data, which focused on investment fund distribution, carry over to retail securities distribution generally.

i. MFDA Channel

As outlined above in our review of the Ipsos Canadian Financial Monitor data and the Investor Economics Household Balance Sheet data, deposit-taker and insurer owned dealers have a strong market presence in the fund industry. This presence also extends across specific registration channels with deposit-taker and insurer owned dealers administering the largest share of assets in the MFDA and IIROC channels.

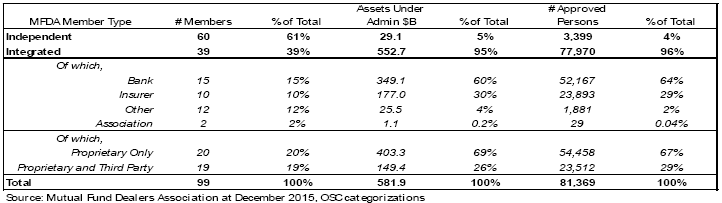

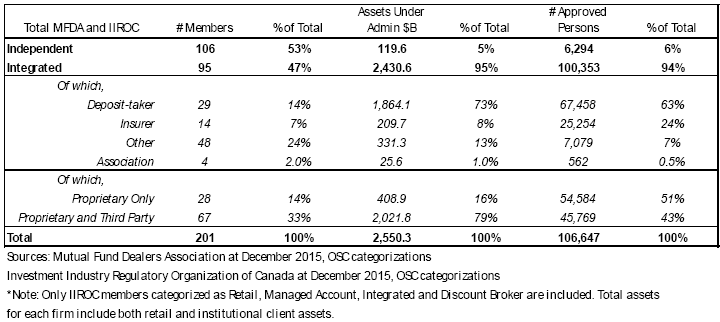

95% of assets in the MFDA channel are administered by integrated dealers{44}

Table 9: MFDA member assets and approved persons by dealer type{45}

The MFDA channel is fairly concentrated and highly integrated. At the end of 2015, there were a large number of both integrated and independent firms in the channel with the majority of firms being independent of asset management. However, the majority of the assets in the channel and approved persons employed were at the integrated firms. At the end of 2015, integrated MFDA firms administered 95% of assets and employed 96% of approved persons in the channel.

90% of assets in the MFDA channel are administered by deposit-taker and insurer owned dealers

The 25 deposit-taker owned and insurer owned MFDA firms administered 90% of assets and employed 93% of approved persons. Independent/Other{46} MFDA firms, while making up 73% of firms in the channel, administered only 9% of assets and employed 6% of approved persons.

Independent MFDA dealers have tended to serve higher-wealth clients

Independent MFDA dealers have tended to serve higher-wealth clients while deposit-taker/insurer owned firms have tended to serve all client types.{47} Deposit-taker/insurer owned dealers had traditionally focused on clients with investable assets up to $250,000 but have increasingly focused on more affluent clients. Typically, mass-market clients will be serviced by front line representatives at the branch, while those with investable assets above $100,000 will be serviced by 'financial planners'{48} at the branch. Clients with assets above $1 million or more will typically be referred to the related IIROC dealer or the related private wealth management arm for service.

For independent/other MFDA firms, typically they will not take on clients unless they have at least $100,000 in investable assets. This information, coupled with our analysis of the Ipsos data, suggests that the majority of households (particularly mass-market households) will be working with a deposit-taker or insurer owned MFDA dealer.

The majority of assets in the MFDA channel today are administered by dealers that focus on proprietary funds

Given that the majority of integrated mutual fund dealer firms limit their product shelf primarily to proprietary products{49}, this restriction also implies that the majority of mass-market households are primarily sold proprietary products. At the end of 2015, 69% of assets in the MFDA channel were held at dealers that focused primarily on proprietary products.

The majority of investment fund owning mass-market households are working with representatives that are not compensated by commissions

For many integrated fund dealers and in particular for the deposit-taker owned fund dealers, compensation for the representative is not derived from commissions but rather through non-activity based transfer payments from affiliated corporate entities.{50} Given that deposit-taker owned fund dealers administered 60% of the assets and employed 64% of approved persons in the channel at the end of 2015 and that these firms tend to service the majority of households with modest levels of investable assets, the majority of mass-market investors today are working with representatives that are not compensated via embedded commissions.

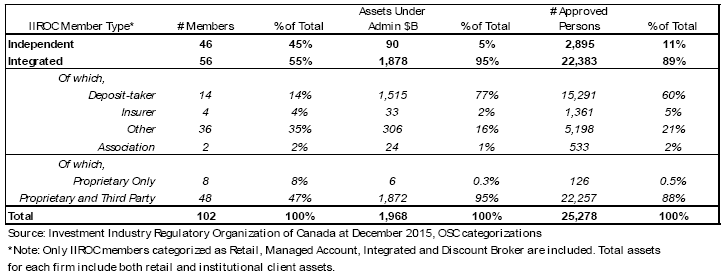

ii. IIROC Channel

95% of retail assets in the IIROC channel are administered by integrated firms

Table 10: IIROC member assets and approved persons by dealer type

The IIROC channel also has a wide range of both integrated and independent dealers. At the end of 2015, integrated IIROC firms administered 95% of assets{51} and employed 89% of approved persons in the channel. Independent dealers -- when one includes the 'other integrated' dealer category, made up 80% of firms, administered 20% of assets and employed 32% of approved persons at the end of 2015. Deposit-taker and insurer owned dealers, while only making up 18% of firms, administered 79% of assets and employed 66% of approved persons.

The IIROC channel is almost entirely "open shelf" today

While slightly less concentrated among integrated dealers than the MFDA channel (where independent and other integrated firms administered 10% of assets) the IIROC channel is still dominated by the deposit-taker owned dealers. Where the two channels differ is with respect to the level of related party product distribution. While the deposit-taker and insurer owned MFDA firms primarily distribute proprietary funds, their counterparts in the IIROC channel are primarily open shelf largely due to the types of representatives employed in this channel. Almost 100% of integrated IIROC firms offer proprietary and third party products. IIROC representatives also have more flexibility and are able to offer a wider variety of security types. Therefore, IIROC representatives tend to be more independent than their MFDA counterparts, even if they are working for a firm that offers their own mutual funds, making them and the whole channel less focused on the sale of proprietary products including proprietary funds.{52}

Deposit-taker-owned IIROC dealers also tend to differ in their methods of compensating representatives relative to their mutual fund dealer peers owned by deposit-takers. Representatives employed by deposit-taker owned IIROC dealers tend to be compensated via commission grid while their counterparts at deposit-taker owned MFDA dealers are typically compensated via salary plus a performance bonus which may impact the way in which the firm can incent behavior in the two channels.

IIROC representatives also tend to be more selective regarding their clientele. IIROC dealers typically aim to service households with investable assets of $500,000 or more, although some IIROC dealers will service clients with lower investable assets.{53} This fact, coupled with what we have highlighted from the Ipsos data, suggests that the potential market for the IIROC channel is roughly 6% to 14% of households. These households are typically the wealthiest households in Canada which is one of the reasons why retail assets under administration in this channel are over three times the size of assets in the MFDA channel. The IIROC channel administers more assets but services fewer households than the MFDA channel.

Table 11: Combined MFDA and IIROC member assets and approved persons by dealer type

We can see that in total, 95% of the assets under administration in Canada are administered by integrated firms. 16% of these assets are administered by dealers that primarily offer proprietary products. As explained above, dealers that only offer proprietary products are concentrated in the MFDA channel. Deposit-taker and insurer owned dealer firms administered 81% of the assets and employed 87% of approved persons. We also note that, at the end of 2015, there were 106,647 registered representatives just in the MFDA and IIROC channels alone{54} servicing a total population of 35.8 million Canadians. This equates to one representative for every 336 Canadians.

By way of comparison, in 2011, the year before the Retail Distribution Review (RDR) reforms were implemented in the United Kingdom (see Appendix C for an overview of the RDR reforms), there were 40,566 advisers registered{55} servicing a total population of 63 million (one advisor for 1,553 people) and only 21% of these advisers were employed by a bank or building society.{56}

This comparison suggests that Canadian investors currently have access to a relatively large number of representatives, particularly in the deposit-taker owned channel. 63% of the representatives were employed by a deposit-taker owned dealer and a further 24% were employed by an insurer owned dealer.

It also suggests that the distribution landscape in Canada is relatively more concentrated and vertically integrated than is the distribution landscape in the United Kingdom.{57}

In the next section, we take a closer look at the online/discount brokerage channel -- the non-advised market for funds.

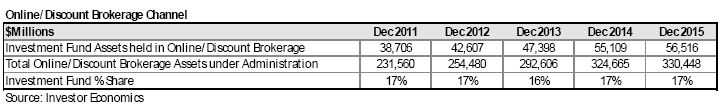

iii. Online/Discount Brokerage Channel

Table 12: Online/discount brokerage assets under administration

The online/discount brokerage channel shows a lower use of investment funds relative to other channels. As shown in Table 12 above, investment funds' share of total assets in the online/discount brokerage channel has been constant over the last five years, remaining at approximately 17% of channel assets over that period. In contrast, investment funds' share of assets in the financial planner/advisor and branch delivery channels stood at 78% and 33% respectively of channel assets at December 2015.{58} In total, there was $330 billion held by do-it-yourself (DIY) investors in the online/discount brokerage channel at December 2015.

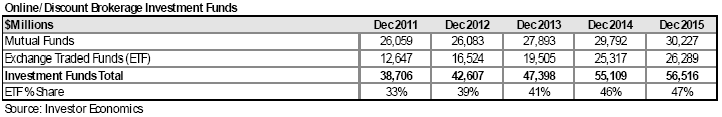

ETFs have become more popular over time with DIY investors

Table 13: Investment funds in the online/discount brokerage channel

ETFs have always been popular with DIY investors and they have become more popular over time. While the share of investment funds held within the online/discount brokerage channel has remained steady, DIY investors' preference between mutual funds and ETFs has moved in favour of ETFs over time. At December 2015, DIY investors held $30 billion in mutual funds and $26 billion in ETFs. ETF assets owned by DIY investors have more than doubled since December 2011 and as a share of total assets in the online/discount brokerage channel, ETFs increased from 33% to 47% over the period.

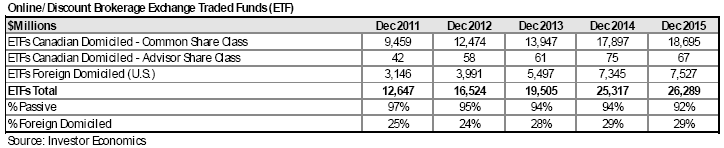

Canadian ETF managers must compete with their U.S. domiciled peers while Canadian mutual fund managers do not

Table 14: ETFs held in the online/discount brokerage channel

Unlike investment fund managers of conventional mutual funds in Canada, investment fund managers of ETFs in Canada must compete both within the Canadian market and compete with ETFs domiciled in other markets, primarily the U.S. market.{59}

DIY fund investors buy both Canadian domiciled and U.S. domiciled ETFs. At December 2015, Canadian DIY investors held $19 billion in Canadian domiciled ETFs and $8 billion in U.S. domiciled ETFs -- fully 29 cents of every dollar invested in ETFs by DIY investors is invested in U.S. domiciled ETFs.

ETFs held in the online/discount brokerage channel are overwhelmingly passively managed

In contrast to the conventional mutual fund space, passively managed funds make up the largest share of assets. At December 2015, passively managed ETFs made up 87% of the Canadian domiciled ETF market. This preference for passively managed products is even more prevalent for Canadian DIY investors investing in ETFs. At December 2015, 92% of ETF assets were held in passively managed ETFs although that market share has declined over the last five years as more actively managed ETFs have entered the market.

The majority of DIY investors investing in mutual funds pay full trailing commission despite not receiving advice

Table 15: Do-it-yourself mutual funds

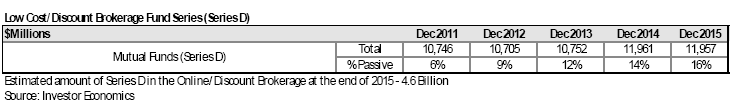

If we look more closely at the types of mutual fund series sold through the online/discount brokerage channel, we see that the majority of fund series sold are the full trailing commission fund series despite the increased availability of Discount/DIY fund series (typically denoted "D" series){60} in the market. Consequently, many DIY mutual fund investors in the online/discount brokerage channel indirectly pay for services they do not receive.

Assets held in the Discount/DIY mutual fund series are however slowly increasing. These assets totaled $12 billion at December 2015 up from $11 billion in December 2011, although by the most recent estimate, the majority of these assets were not held in the online/discount brokerage channel. At the end of 2015, it is estimated that out of the total $12 billion of Discount/DIY fund series assets, only $4.6 billion was actually held in the online/discount brokerage channel.{61} This data suggests that $25 billion of the total $30 billion held in mutual funds in the channel (83%) remains in the full trailing commission paying fund series.

As is the case for many DIY mutual fund investors in the online/discount brokerage channel, there are also some DIY ETF investors that indirectly pay trailing commissions without receiving advice because they hold the trailing commission paying "Advisor" class units of the ETF.{62} However, the amount of assets held in these "Advisor" class units is relatively low (only $67 million at December 2015) in comparison to the share of full trailing commission paying mutual funds in the online/discount brokerage channel.

Finally, we note that unadvised fund investors as a group (those buying Discount/DIY fund series) have a higher share of assets invested in passively managed mutual funds relative to advised mutual fund investors.

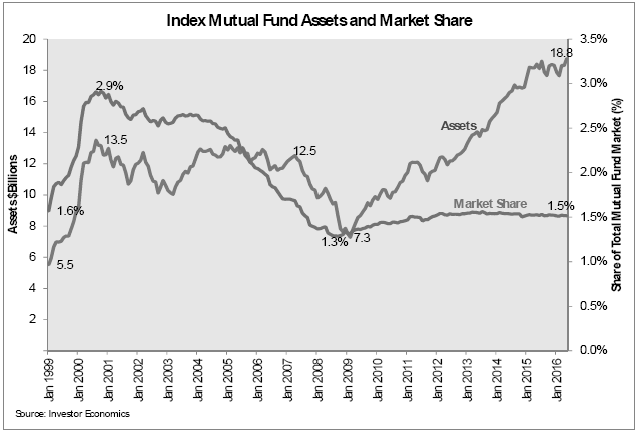

At the end of 2015, 1.5% of total mutual fund assets (excluding ETFs) were held in passively managed funds. Index fund market share has remained essentially unchanged over the last 10 years. However among the relatively new Discount/DIY fund series, index funds made up a much larger share of assets (16% or $2 billion) that has been growing steadily over time.{63}

Figure 4: Index mutual funds in Canada

We now turn our attention to some important facts about investment fund managers.

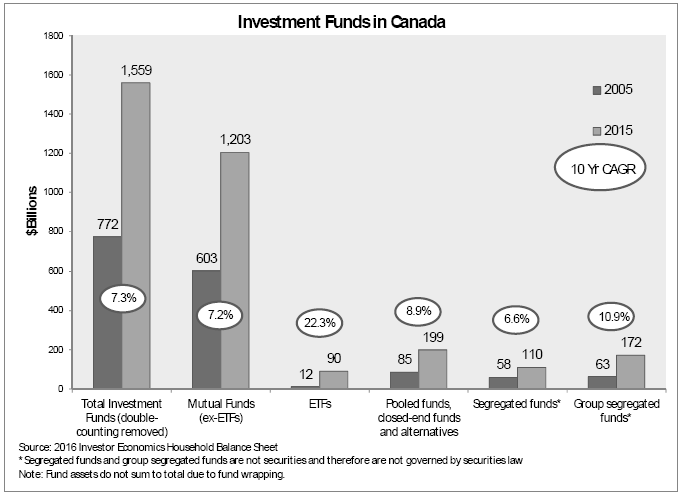

c. Investment Fund Management

Mutual funds are by far the dominant type of investment fund sold in Canada today. This has been the case since organized investment fund asset monitoring in Canada started in the early 1990s. At the end of 2015, Canadians held $1.2 trillion in mutual fund assets, $90 billion in ETF assets, $110 billion in segregated fund{64} assets, $172 billion in group segregated fund assets, and $199 billion in pooled fund, closed end funds and alternative fund assets. Although there have been articles at various times in the past regarding the growth of ETFs and segregated funds, and despite impressive annual growth rates for ETFs, the dominance of mutual funds has never been challenged in a significant way.{65}

Figure 5: Investment funds by fund type

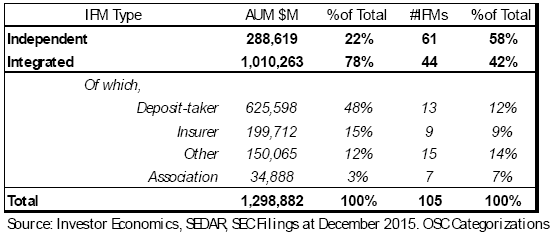

Fund management is concentrated but is less concentrated than fund distribution

Table 16: Mutual funds by investment fund manager type