Social Media and Retail Investing: The Rise of Finfluencers

Executive Summary

Executive Summary

The rise of social media has given way to a new wave of financial influencers, or “finfluencers”, who leverage their platforms to share insights on finance and investing with their audiences. This trend has transformed how retail investors engage with financial markets.[1] In response, the Ontario Securities Commission (OSC) has collaborated with The Decision Lab (TDL) to explore the relationship between Canadian retail investors and the financial information they encounter on social media. The current report includes a literature review, an environmental scan (i.e., a survey and social media data extraction), as well as an online experiment. The online experiment assessed the impact of finfluencers, as well as mitigation strategies to combat misinformation from finfluencers on investing behaviours.

A “finfluencer”, or financial influencer, is an online personality who offers advice, tips, and guidance on how to manage money, invest wisely, and/or achieve financial goals. Finfluencers generally fall into one of three categories: unregistered individuals, unregistered individuals hired by financial firms, and registered investment advice professionals. While some finfluencers may offer quality advice or guidance, others may have ulterior motives, questionable credentials, or be subject to various incentives, affecting the quality of advice offered. The intent of this report is not to distinguish helpful finfluencers from harmful finfluencers, but rather, to provide an assessment of the capacity of finfluencers to influence retail investor behaviour and identify mitigation strategies where finfluencer advice or guidance poses investor protection concerns.

Finfluencer Persuasion Techniques and Mitigation Strategies

Finfluencer messages often share common characteristics that enhance their effectiveness. Messages that successfully influence behaviour typically employ various persuasion techniques. Additionally, two psychological factors—message concreteness and emotional tone—play a significant role in a message’s persuasiveness. Concrete messages are more specific messages, providing detailed information often aided by practical examples or instructions. On social media, concrete messages are generally perceived as more credible, thereby increasing their potential to influence recipients. Emotional tone refers to the positive, neutral, or negative emotions conveyed within a message. Social media studies have indicated that messages with a positive tone are more likely to spread than messages with a neutral or negative tone.

To counter the persuasiveness of social media content, we identified several effective mitigation strategies through our desk research. One such strategy is disclosure, which involves revealing information that may impact a recipient’s understanding or perception of a message. Another effective intervention is prebunking, which pre-emptively exposes and counteracts misinformation or biased perspectives before the audience encounters them. Inoculation works similarly by presenting a weak version of the persuasive message but then refuting it, thereby building ‘immunity’ against future messages. Lastly, a nudge can be used to subtly influence choices. For example, before sharing misleading content, nudging users with a message to consider the accuracy of the information they are about to share can reduce sharing behaviour.

Social Media Attitudes and Behaviours of Canadian Retail Investors

We conducted a survey with 655 Canadian retail investors to understand their attitudes and behaviours towards finfluencers. Among those surveyed, 91% were active social media users. Key findings included:

- The three most commonly used social media platforms for accessing financial information were YouTube (34%), Reddit (22%), and Instagram (21%).

- 35% of respondents reported making a financial decision based on advice from a finfluencer.

- Popular self-reported reasons for using social media for financial advice included the perceived ease of access, simplicity, cost-free nature, and informativeness of the content.

- Although retail investors are generally distrustful of finfluencers, they are more likely to follow the recommendations of the few finfluencers they trust.

- Of those who have made financial decisions based on finfluencer advice, they are also more likely to:

- have been scammed on social media (12.2 times more likely).

- trust the financial influencers they follow (7.2 times more likely).

- trade stocks or other investments frequently, several times a week (4.9 times more likely).

- believe the financial influencers they follow provide useful information (3.6 times more likely).

- are willing to take moderate risks and accept some losses to potentially earn higher returns (3.2 times more likely).

- have experienced significant investment losses in the past (2.3 times more likely).

- manage their investments using a self-service mobile app (2.2 times more likely).

- Of those who have made financial decisions based on finfluencer advice, they are also less likely to:

- work with a financial advisor or portfolio manager (3.1 times less likely).

- spend less than one hour on social media per day (2.8 times less likely).

The Experiment

We conducted an online randomized controlled trial (RCT) to examine the influence of finfluencer posts on retail investor behaviour and the effectiveness of mitigation techniques. A total of 1,465 Canadian social media users (59% real-life retail investors) completed a trading simulation, where they could trade various assets, including individual stocks, ETFs, and crypto assets. Each participant started with a fictional balance of $10,000 and aimed to maximize returns. To study the impact of finfluencer content on trading behaviour, we exposed participants to a range of social media posts—some promoting certain assets—between certain trading rounds. We also introduced mitigation techniques to some participants such as disclosure, prebunking, inoculation, and nudges. We compared the behaviours of these participants to a control group.

Our experimental findings showed:

- Social media impacted trading behaviour. Specifically, 24% of participants exposed to finance-related social media posts—without any intervention—purchased the promoted assets, compared to 7% of those who did not see such posts.

- Exposure to finance-related social media content led to 21% of investors purchasing the promoted asset, compared to 29% of non-investors. This suggests that non-investors may be more likely to be influenced by financial information on social media but may also benefit more from protective interventions.

- Disclosures, prebunking, and inoculation all reduced the proportion of participants purchasing finfluencer-promoted assets, indicating these mitigation strategies can protect investors from social media-driven influence. However, none of these interventions fully mitigated the influence of social media posts.

- We did not observe any significant difference in overall trading volume across conditions, suggesting that while finfluencer content may focus trading activity on specific assets, it may not affect total trading volume overall.

Conclusion

From the perspective of retail investors, financial advice on social media is valuable due to its perceived ease of access, perceived ease of understanding, cost-free nature, and informativeness. However, the quality of this advice varies widely, and our research highlights several concerns about its impact on retail investors.

Our survey reveals that while retail investors generally view finfluencers as self-interested, many still trust the ones they follow. This trust disparity can make investors vulnerable to low-quality advice. Our experiment further demonstrates that finfluencer recommendations can significantly influence retail investors’ trading decisions. Although finfluencer-investor relationships are not inherently harmful, they have the potential to negatively impact investor well-being if the finfluencer is providing low quality advice, due to a lack of expertise on their part or ulterior motives to generate commissions, followers, or other incentives.

The research supports the use of interventions such as disclosures, prebunking, and inoculation to mitigate the persuasive effects of social media content on investor behaviour. These interventions could be implemented at scale by authorities through, for instance, advertising on social media platforms.

Overall, our findings indicate that finfluencer content on social media significantly influences retail investors’ attitudes and financial decisions. This research underscores the need to consider investor harms as a result of finfluencer activity and the need for ongoing regulatory oversight, and provides evidence-based approaches that authorities could use to decrease these harms.

In Canada, key guidance regarding finfluencer actions has been developed by the CSA, OSC, and IIROC (now CIRO).[2]

However, in light of the amplified impact that ‘finfluencers’ can have on retail investors, authorities could consider further measures to directly address these concerns.

[1] World Economic Forum. Are 'finfluencers' the future of financial advice? https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/07/finfluencer-financial-advice-social-media/

[2] International Organization of Securities Commissions (2024). Finfluencers. pp. 31-32. https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD775.pdf

Introduction

Introduction

According to the 2024 Canadian Securities Administrators Investor Index[3]:

“More Canadians are using social media for investment information. Investors who use social media for investment information increased by 18% since 2020 to 53%. Notably, 82% of 18- to 24-year-old investors use social media, with YouTube, Instagram and TikTok being the most popular choices in this age group. Moreover, 46% report encountering investment opportunities on social media, which is a 17% increase from 2020, and is also especially common among younger age groups.”

This proliferation of social media use has given rise to social media financial influencers—individuals who leverage their online followings to influence their followers, often, albeit not exclusively, for financial benefit. Often called “finfluencers”, they cultivate followings within the financial realm and uses their platform to share insights and information related to finance and investing. The rise of finfluencers is one example of how social media has changed the way consumers, retail investors, and even institutions interact with financial markets. Financial discourse on social media also includes less centralized communities, forums, or discussion boards where ideas and information are exchanged.

This research report by the Ontario Securities Commission (OSC) in collaboration with The Decision Lab (TDL), explores the relationship between Canadian retail investors and the financial information they encounter on social media. It aims to assess the impact of finfluencers on retail investor attitudes and behaviour. This research is of particular relevance given the rapid increase of financial advice on social media, which carries both benefits and risks for investors. In this report, we take a systematic approach to assessing the risks that finfluencers and social media pose to retail investors, while also exploring the capacity of behavioural interventions to mitigate these risks. This research does not explore the potential benefits of accessing financial information through social media, but we recognize that there are elements of this landscape that can be beneficial for retail investors.

This report consists of a literature review, an environmental scan (i.e., a survey and social media data extraction), and a randomized controlled trial to provide a comprehensive assessment of the impact of finfluencers and social media on retail investor behaviour. The report also provides insight into strategies to improve the welfare of retail investors.

[3] Canadian Securities Administrators (2024), 2024 CSA Investor Index.

Literature Review

Literature Review

The first component of our research consists of a literature review to assess the messaging characteristics commonly found within finfluencer content, as well as an assessment of mitigation strategies.

A “finfluencer”, or financial influencer, is an online personality who offers advice, tips, and guidance on how to manage money, invest wisely, and achieve financial goals. While some finfluencers may be legitimate experts or operate under the supervision of a registered firm, social media platforms do not require accreditation or licensing to share financial information or advice. Finfluencers generally fall into one of three categories: unregistered individuals, unregistered individuals hired by financial firms, and registered investment advice professionals. Most finfluencers are not affiliated with registered broker-dealers or investment advisers, yet they disseminate information that retail investors may find difficult to distinguish from professional investment advice. Their influence on retail investors’ behaviour is expected to grow, partly because they present complex information in an engaging and accessible manner and appear in venues frequented by younger investors.

While some finfluencers may offer advice or guidance that is of high quality, others may have ulterior motives, questionable credentials, or be subject to various incentives, affecting the quality of advice offered. The intent of this report is not to distinguish helpful finfluencer from harmful finfluencers, but rather, to provide an assessment of the capacity of finfluencers to influence retail investor behaviour. Social media is a source of information, and that information may be of high or low quality. Our research demonstrates the capacity of information found on social media to cause both benefit and harm, thereby reinforcing the need for stakeholders to ensure that a balance is struck between retail investor experience and protection.

The ability of social media content to influence retail investors is driven in part by the persuasiveness of the finfluencers’ message. Stronger messages are more effective at shaping the beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours of their followers. More effective messages likely contain at least some of the six fundamental persuasion techniques (see Table 1).[4] These persuasion techniques, when used by finfluencers, may lead investors to make financial decisions that they otherwise would not have made.

Table 1. Six Principles of Persuasion

| Persuasion Technique | Explanation | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Authority | People are more likely to comply with a request if it comes from a recognized authority figure or someone perceived as an expert in a specific field. | A finfluencer may make claims about their own financial successes to create a perception of authority. |

| Scarcity | People are more likely to value things are the in limited supply or only available in a short time frame. | A finfluencer might emphasize the limited time frame or availability of an investment opportunity, creating a sense of urgency. |

| Social Proof | People tend to follow the actions of others, especially when they are uncertain about what to do. | A finfluencer might share a post about their recent successful stock picks, showcasing positive comments and testimonials from followers who profited. |

| Reciprocity | People feel obligated to give back when they receive something from others. | A finfluencer might offer exclusive insights or a free educational webinar on investment strategies to ask for investments in the future. |

| Liking | People are more likely to be influenced by those they know, like, and find similar to themselves. | A finfluencer may be attractive, and/or may share positive personal stories or interests on their social media platforms to be likable. |

| Commitment and Consistency | People have a natural desire to be consistent with their previous beliefs or behaviours. | A finfluencer may encourage followers to make a small commitment, such as sharing their financial goals. Then, they would later ask them for a larger request, such as funding an investment. |

In addition to these persuasion techniques, two other psychological characteristics related to the persuasiveness of messages are concreteness and emotionality.

Concreteness refers to the level of specificity within a message. A concrete message is narrower and more specific, providing detailed information often aided by practical examples or instructions. In contrast, an abstract message is broader and more generalized, often focusing on higher-level concepts such as goals or principles. On social media, concrete messages are generally viewed as more credible, resulting in an increased potential to influence the recipient of the message.[5]

Emotional tone refers to the positive, neutral, or negative emotions conveyed within a message. Most social media studies find that messages with a positive tone are capable of driving emotional contagion—that is, the transfer of emotions from one individual to another. During the meme stock phenomenon, investment in GameStop illustrated how positive emotion contagion could drive investing behaviours en masse. It has been also noted that for crypto assets, which may be volatile and sentiment-driven, negative emotions seem to be more contagious and may spread more easily through social networks compared to positive emotions.[6] See Table 2 for examples of messages with different levels of Concreteness and different emotional tones.

Table 2. Message Concreteness and Emotional Tone Examples

| Abstract | Concrete | |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Emotional Tone |  |  |

| Negative Emotional Tone |  |  |

[4] Cialdini, R. B., & Cialdini, R. B. (2007). Influence: The psychology of persuasion (Vol. 55, p. 339). New York: Collins.

[5] Balaji, M. S., Jiang, Y., & Jha, S. (2021). Nanoinfluencer marketing: How message features affect credibility and behavioral intentions. Journal of Business Research, 136, 293-304.

[6] Meyer, E. A., Sandner, P., Cloutier, B., & Welpe, I. M. (2023). High on Bitcoin: Evidence of emotional contagion in the YouTube crypto influencer space. Journal of Business Research, 164, 113850.

To counter the persuasiveness of social media content, we turn to the strategies that have been demonstrated to enhance the resilience of recipients to persuasive messaging.[7] These strategies aim to strengthen an individual's ability to critically evaluate the content of persuasive messages. We focused on four messaging interventions, which were selected due to robust evidence and/or a similarity to current strategies used by authorities.

Disclosure

A disclosure refers to the act of revealing information that may impact a recipient’s understanding or perception of a message. Within the context of social media, a common form of disclosure is to clarify a conflict of interest that a finfluencer may have in the promotion of a particular product. For example, a finfluencer may disclose that they were paid to promote a given financial product.

While disclosures are commonly used, several studies suggest that they can increase, rather than decrease, trust in the message.[8],[9],[10] Specifically, research has found that disclosures in advertising can increase the perceived credibility of the finfluencer, which in turn has a positive effect on the recipient’s purchase intention.[11] In essence, the act of disclosure can make the messenger seem more trustworthy.

There is also little existing evidence in terms of where disclosures should be positioned. As a result, many disclosures are made in the final moments of a piece of media (e.g., within a video), and may not be viewed at all. Furthermore, disclosures of financial conflicts of interest are irrelevant to certain forms of social media-driven scams (e.g., pump and dumps), where there is no financial relationship between the finfluencer and the company behind the security. These findings call into question the effectiveness of disclosure at mitigating the persuasive impact of low-quality financial recommendations or advice on retail investors.

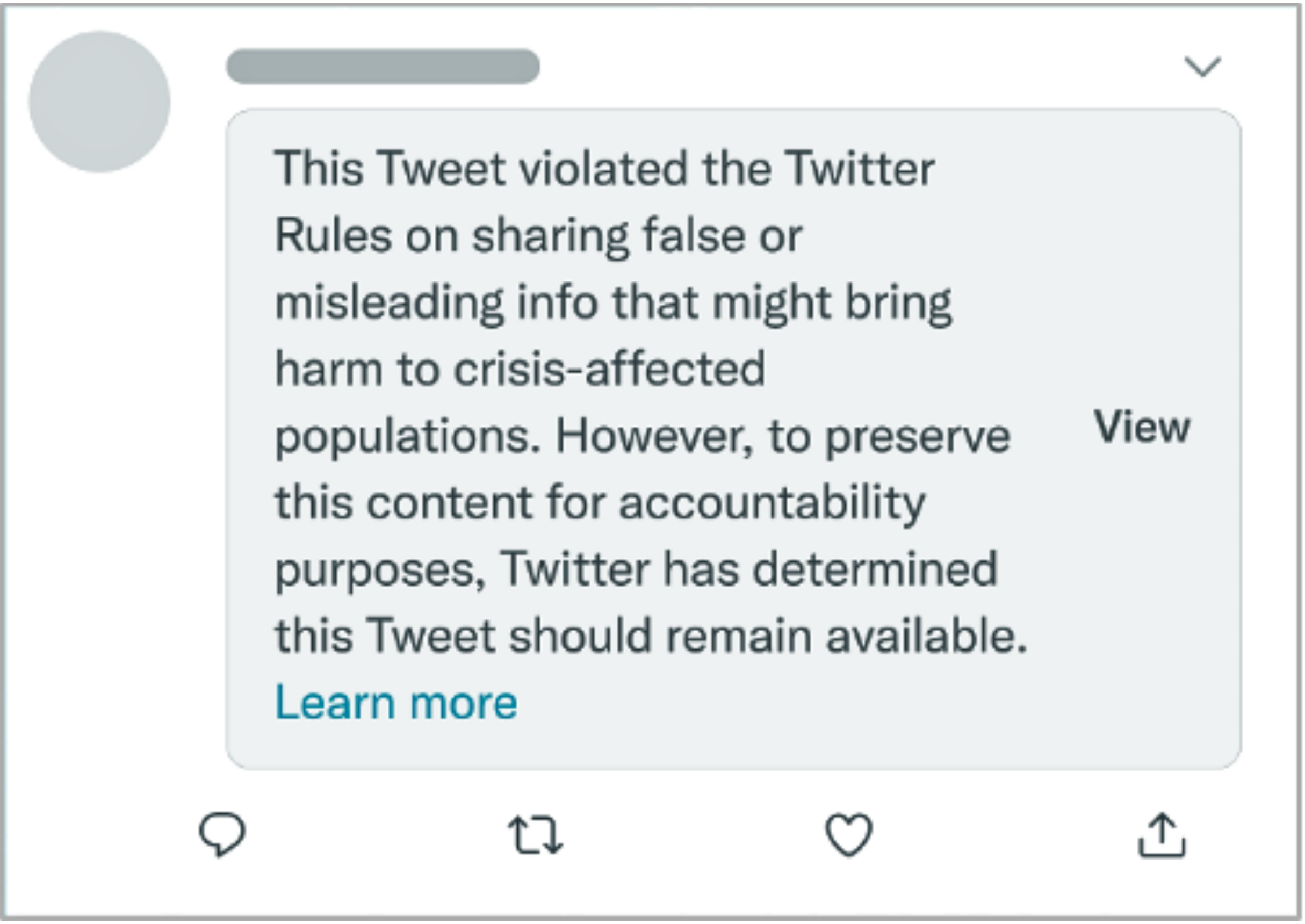

Prebunking

An intervention that has shown effectiveness when it comes to combatting misinformation on social media is pre-exposure or prebunking. In contrast to the traditional approach of debunking, in which a message is discredited after it has been delivered, prebunking aims to discredit misleading claims before they are made. As the prebunking is provided in advance, it tends to be general, partly because the recipient does not yet know the specifics of the message. Still, prebunking has been shown to develop resistance to persuasion tactics. The effectiveness of this strategy demonstrates that interventions may not necessarily need to be tailored to the specific message. The most common prebunking interventions present general, yet factually correct information, a pre-emptive correction (e.g., a true/false tag), or a generic misinformation warning (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Example of Misinformation Warning on X (Twitter)

Overall, prebunking messages have been found to increase skepticism of online information, suggesting that it may be an effective strategy to curb the persuasive effect of low-quality financial information or misinformation found on social media.

Inoculation

Inoculation is similar to a medical vaccine; it exposes people to a weakened version of a persuasive message to build their resistance to similar types of persuasive messages in the future.[12],[13],[14] Unlike prebunking, which presents factual information prior to the persuasive message, inoculation relies on debunking weakened examples of persuasive messages to build resistance against future persuasive messages.

For example, imagine a campaign designed to prevent investment scams using the inoculation technique. The campaign presents a common, poorly crafted scam tactic, such as a get-rich-quick scheme with guaranteed returns. This initial scam is then dissected and debunked by explaining that legitimate investments never promise high returns without risk, and such guarantees are clear red flags for scams. By doing this, the campaign helps people recognize and critically evaluate similar and more compelling investment scams in the future. In contrast, with a prebunking approach, the audience would not be provided with an example scam—instead, they would receive some factual information about scams in general (e.g., the typical language used in investment scams, such as “risk-free investment”) prior to encountering the actual scam.

While prebunking focuses on providing fact-based corrections, inoculation emphasizes logic-based corrections like pointing out the techniques used.[15] Thus, there is an additional learning component in inoculation that is not present in prebunking. By virtue of promoting critical thinking and using logic, as opposed to addressing the specific content of messages, inoculation interventions can be broader in scope and generally more enduring.

Nudge

Disclosure, prebunking, and inoculation are messaging interventions that provide additional information to the message recipient, either via the finfluencer themselves or through a third party. In contrast, a nudge is a subtle change to the decision-making context that is intended to predictably influence the decision without restricting the choices available.[16] While a nudge may also involve the provision of additional information, it is focused on changing the context and not necessarily the information provided.

Prior research on misinformation has found that nudges can be effective at influencing behaviour. For instance, before sharing misleading content, nudging users to consider the accuracy of the information they are about to share has been found to reduce sharing behaviour.[17],[18],[19] This is also the case when the nudge highlights the importance of only sharing accurate information.[20] Similarly, with respect to privacy on social media, nudges that remind users of their audience led users to make better decisions regarding what to post and where to post it.[21]

A nudge may not be mutually exclusive from a message that includes a disclosure, prebunking, or inoculation. Rather, a nudge may act as a vehicle for one of these strategies to be added to the decision-making context. Past research has also found that the timing of a messaging intervention is important, with interventions delivered in close proximity to the timepoint at which a decision is made being more effective.[22]

[7] Ecker, U. K., Lewandowsky, S., Cook, J., Schmid, P., Fazio, L. K., Brashier, N., ... & Amazeen, M. A. (2022). The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1(1), 13-29.

[8] Breves, P., Amrehn, J., Heidenreich, A., Liebers, N., & Schramm, H. (2021). Blind trust? The importance and interplay of parasocial relationships and advertising disclosures in explaining influencers’ persuasive effects on their followers. International Journal of Advertising, 40(7), 1209-1229.

[9] Hayes, J. L., Golan, G., Britt, B., & Applequist, J. (2020). How advertising relevance and consumer–Brand relationship strength limit disclosure effects of native ads on Twitter. International Journal of Advertising, 39(1), 131-165.

[10] Kay, S., Mulcahy, R., & Parkinson, J. (2020). When less is more: the impact of macro and micro social media influencers’ disclosure. Journal of marketing management, 36(3-4), 248-278.

[11] Sesar, V., Martinčević, I., & Boguszewicz-Kreft, M. (2022). Relationship between advertising disclosure, influencer credibility and purchase intention. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(7), 276.

[12] Cook, J., Lewandowsky, S., & Ecker, U. K. (2017). Neutralizing misinformation through inoculation: Exposing misleading argumentation techniques reduces their influence. PloS one, 12(5), e0175799.

[13] Van der Linden, S., Leiserowitz, A., Rosenthal, S., & Maibach, E. (2017). Inoculating the public against misinformation about climate change. Global challenges, 1(2), 1600008.

[14] Bode, L., & Vraga, E. K. (2015). In related news, that was wrong: The correction of misinformation through related stories functionality in social media. Journal of Communication, 65(4), 619-638.

[15] Cook, J., Ellerton, P., & Kinkead, D. (2018). Deconstructing climate misinformation to identify reasoning errors. Environmental Research Letters, 13(2), 024018.

[16] Choice architecture refers to the design of different ways in which choices can be presented to consumers, influencing their decision-making and behavior.

[17] Clayton, K., Blair, S., Busam, J. A., Forstner, S., Glance, J., Green, G., ... & Nyhan, B. (2020). Real solutions for fake news? Measuring the effectiveness of general warnings and fact-check tags in reducing belief in false stories on social media. Political behavior, 42, 1073-1095.

[18] Mena, P. (2020). Cleaning up social media: The effect of warning labels on likelihood of sharing false news on Facebook. Policy & internet, 12(2), 165-183.

[19] Nekmat, E. (2020). Nudge effect of fact-check alerts: Source influence and media skepticism on sharing of news misinformation in social media. Social Media+ Society, 6(1), 2056305119897322.

[20] Pennycook, G., Epstein, Z., Mosleh, M., Arechar, A. A., Eckles, D., & Rand, D. G. (2021). Shifting attention to accuracy can reduce misinformation online. Nature, 592(7855), 590-595.

[21] Wang, Y., Leon, P. G., Scott, K., Chen, X., Acquisti, A., & Cranor, L. F. (2013, May). Privacy nudges for social media: an exploratory Facebook study. In Proceedings of the 22nd international conference on world wide web (pp. 763-770).

[22] Fernandes, D., Lynch Jr, J. G., & Netemeyer, R. G. (2014). Financial literacy, financial education, and downstream financial behaviors. Management science, 60(8), 1861-1883.

Environmental Scan

Environmental Scan

The second component of our research, an environmental scan, consists of (1) a survey of retail investors and (2) a data extraction of social media content. The retail investor survey was designed to assess the attitudes and behaviours of Canadian retail investors with respect to finfluencers. The data extraction highlights the prevalence of persuasion techniques (i.e., concreteness and emotional tone) within relevant social media content.

We surveyed 655 Canadian retail investors aged 18 and above to better understand the attitudes and behaviours of these individuals and identify potential risks in the social media landscape. Of the Canadians surveyed, 91% of those surveyed were active social media users. We conducted the survey from July 31 to August 13, 2023.

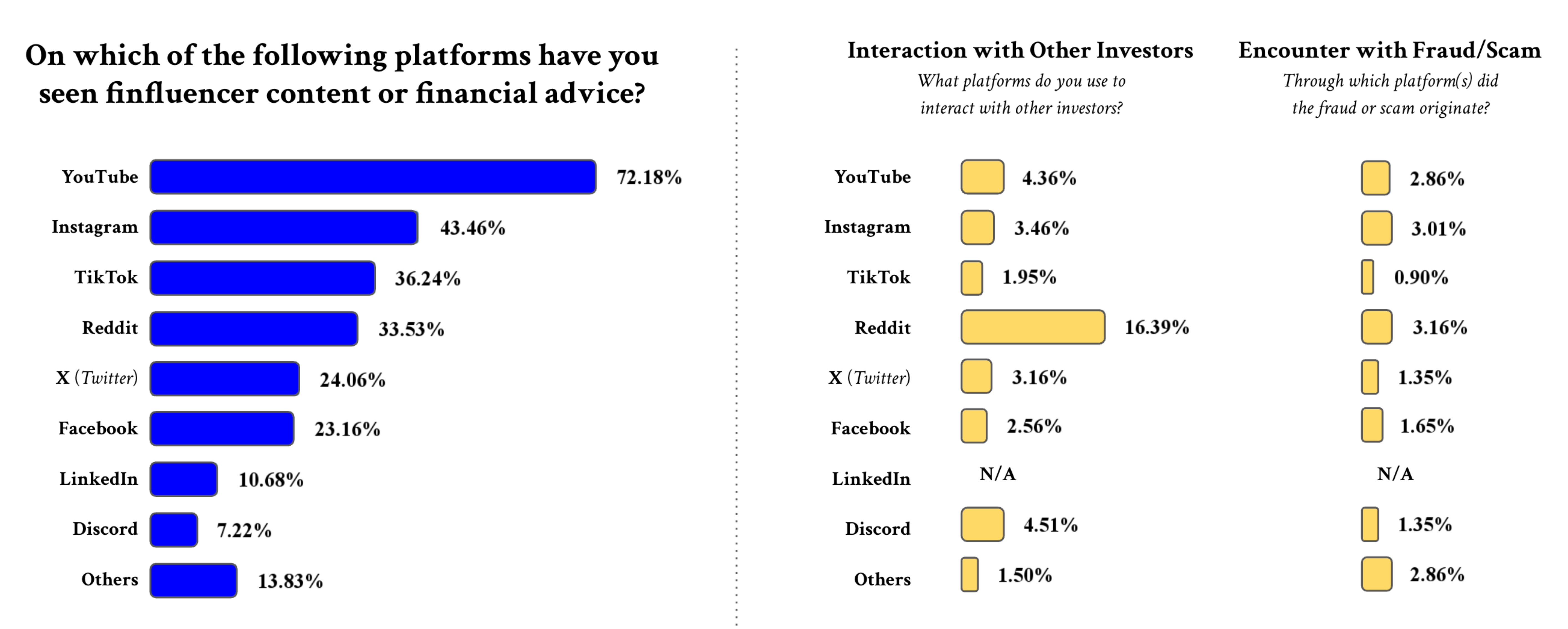

Social Media Usage

We identified three social media platforms most often used to access financial information, which were YouTube (34%), Reddit (22%), and Instagram (21%). We also characterized how users interact with these platforms, with each other, and with successful scammers (Figure 2). YouTube had the highest amount of activity related to the promotion of financial advice, while Reddit had the highest amount of engagement between retail investors. Importantly, successful scams were more likely to have originated from Reddit and Instagram compared to YouTube. In the case of Reddit, engagement between users may provide opportunities for scammers. In the case of Instagram, the short-form media type may lessen the opportunity to recognize a disparity between high quality and fraudulent advice.

Figure 2. User Interactions with Social Media by Platform

Using Financial Advice on Social Media

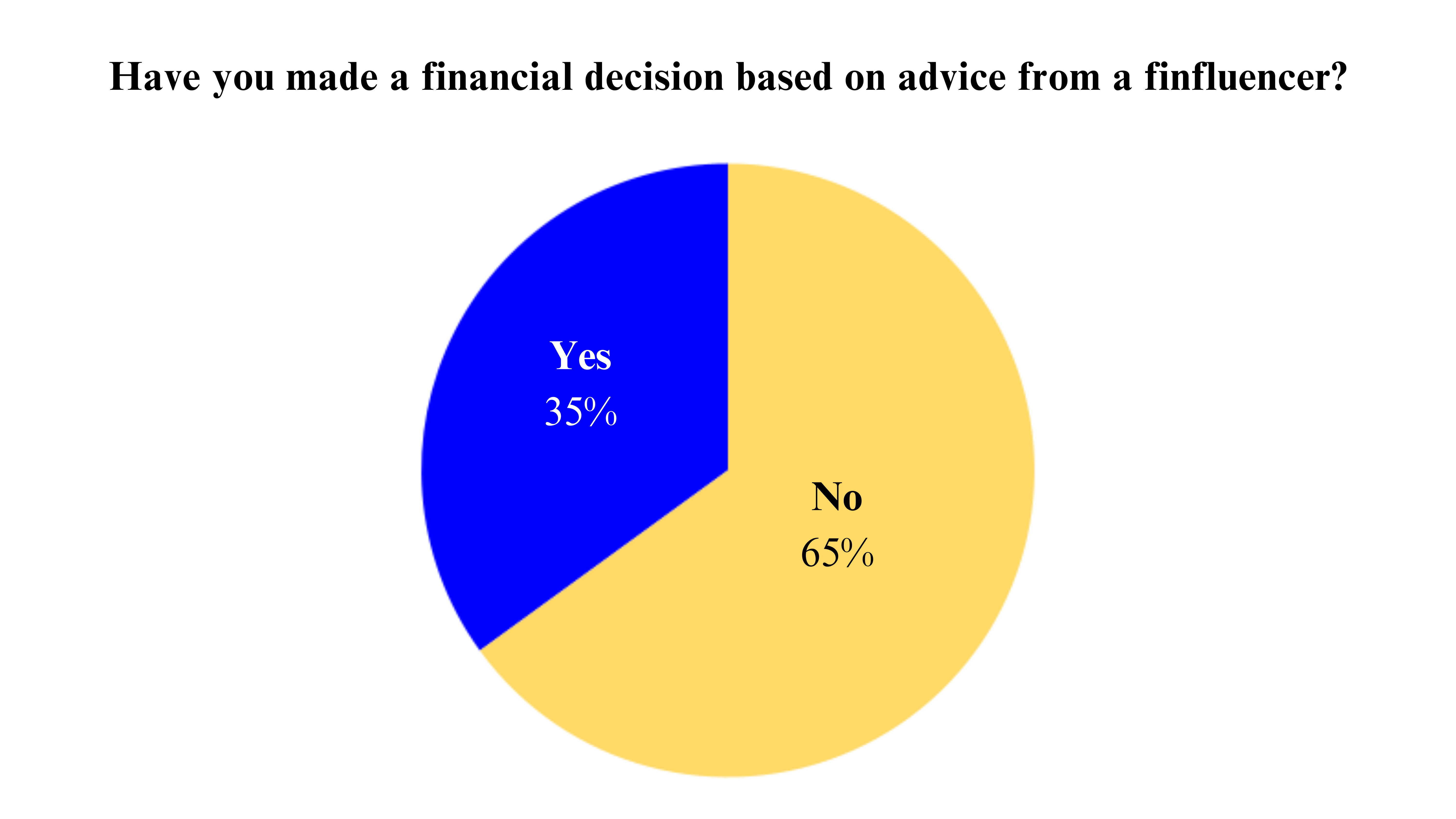

As part of our survey data analysis, we divided participants based on whether or not they had made a financial decision based on finfluencer advice (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Financial Decision Based on Finfluencer Advice

Approximately 35% of respondents reported that they had made a financial decision based on advice from a finfluencer. This is similar to results found in another recent survey, which found social media to be the third most common source of financial information at 39%—trailing only family and friends (50%) and banks (49%).[23]

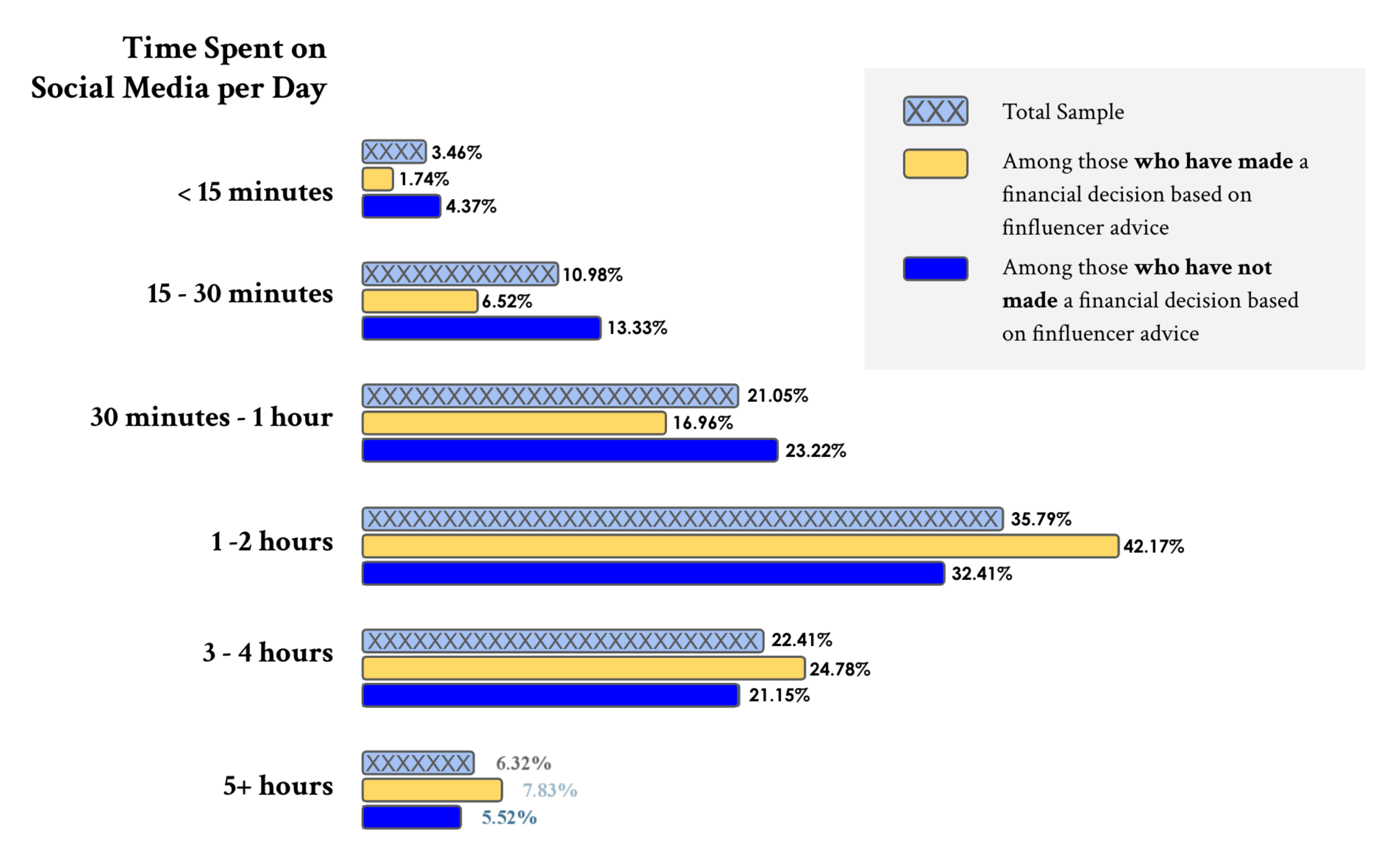

Of those who have made a finfluencer-motivated financial decision, 74% use social media more than one hour per day, whereas 64% of those who have not made such decisions use social media more than one hour per day (see Figure 4). While we cannot determine the causal direction of this relationship, this finding may suggest a relationship between time spent on social media and a propensity to use social media to inform financial decisions.

Figure 4. Time Spent on Social Media

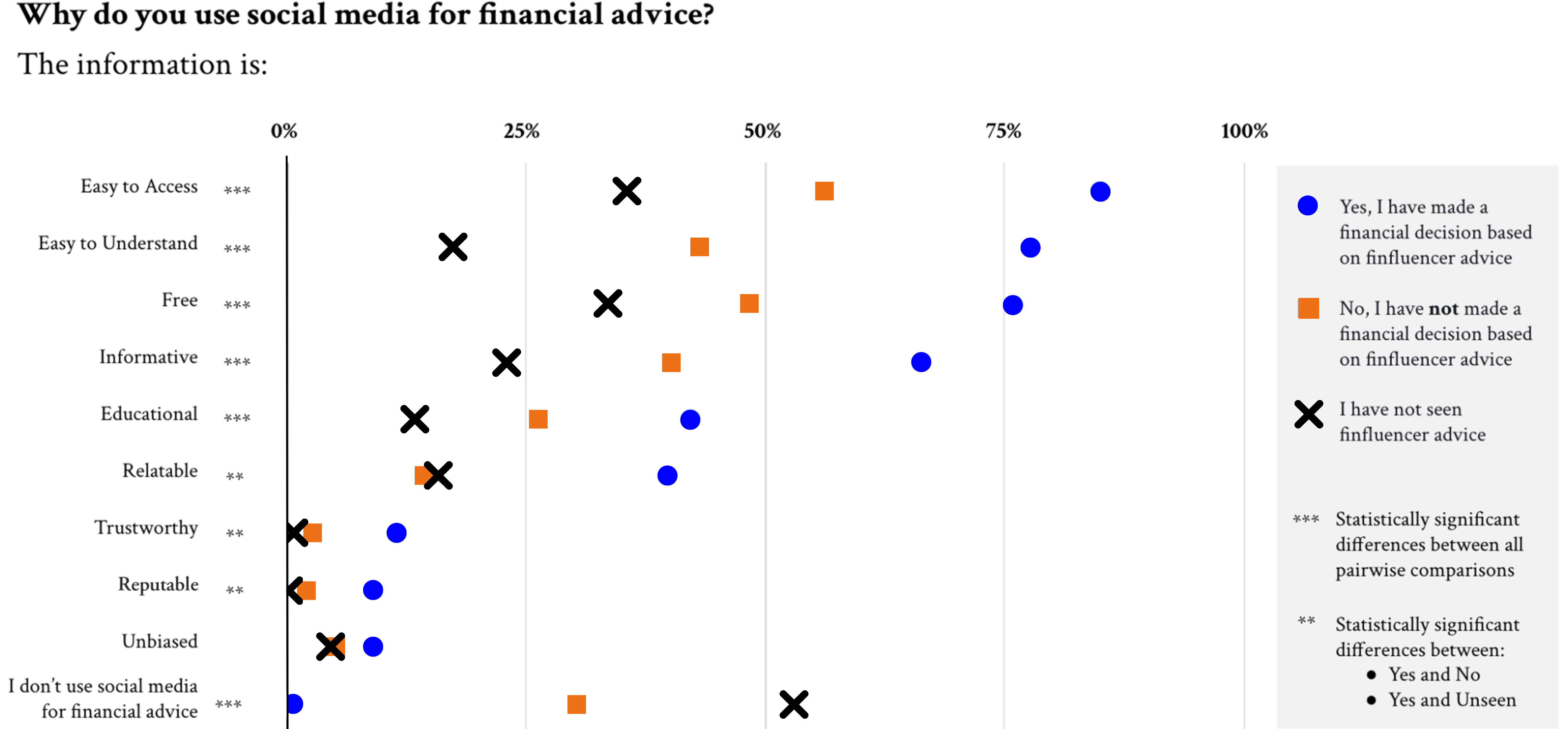

Those who have made financial decisions based on finfluencer advice are significantly more likely to endorse almost all motives for using social media for financial advice than those who have not (see Figure 5). Popular self-reported reasons of using social media for financial advice include the perceived ease of access, perceived ease of understanding, being free, and being informative. These views are held by the majority of respondents who have made a decision due to the recommendation of a finfluencer. Notably, there is a significant drop in the proportion of respondents who view finfluencer content as ‘educational’ compared to those who find it ‘informative’. This suggests that while social media can offer useful information, it may not effectively foster long-term financial knowledge.

Figure 5. Motivations for Using Social Media for Financial Advice

Interestingly, the percentage of respondents who said they used social media for financial advice because it was trustworthy or reputable was quite low, even amongst respondents who have made decisions due to finfluencer recommendations. This suggests that general trustworthiness and reputability are not common drivers of using advice on social media to guide financial decisions.

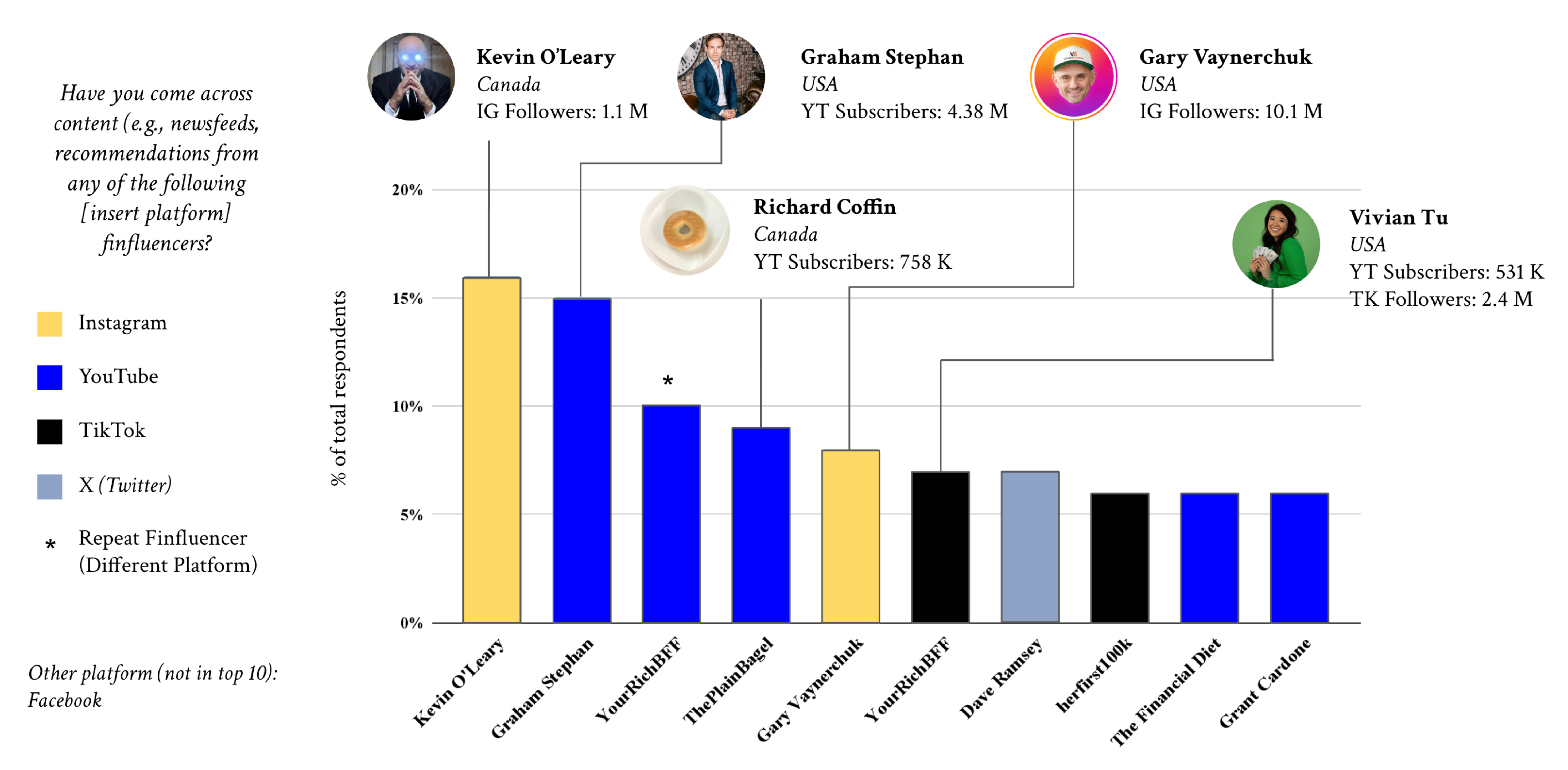

Popular Finfluencers

In our survey, we also identified the top finfluencers followed by retail investors across platforms. Widely known finfluencers include Kevin O’Leary, Graham Stephan, Richard Coffin, Gary Vaynerchuk, and Vivian Tu (see Figure 6). O’Leary and Vaynerchuk are most recognized on Instagram, Stephan and Coffin on YouTube, and Tu on Tiktok.

Figure 6. Most Followed Finfluencers (as of August 2023)

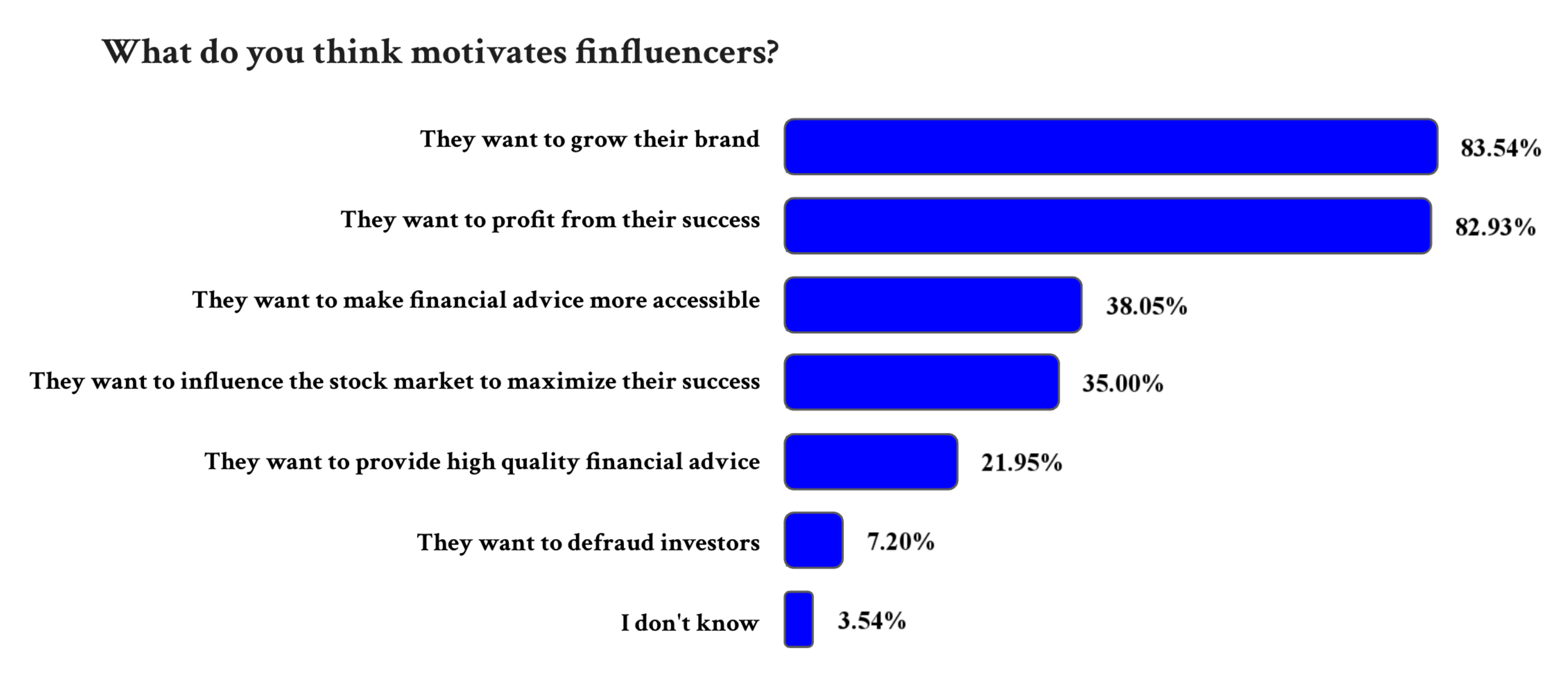

Perceptions of Finfluencers

Retail investors hold a variety of views when it comes to the motivations of finfluencers for posting content on social media. However, an overarching belief is that finfluencers are primarily self-interested. 83% of respondents believe that finfluencers want to grow their brand and profit from their success (see Figure 7). Furthermore, 35% of respondents report that finfluencers are motivated to influence the stock market to maximize their own success, while 38% believe that finfluencers want to make financial advice more accessible. These findings suggest that retail investors generally perceive finfluencers to be self-interested, but this does not appear to have a material impact on the likelihood of investors acting on finfluencer advice when making financial decisions.

Figure 7. Perceived Motivations of Finfluencers

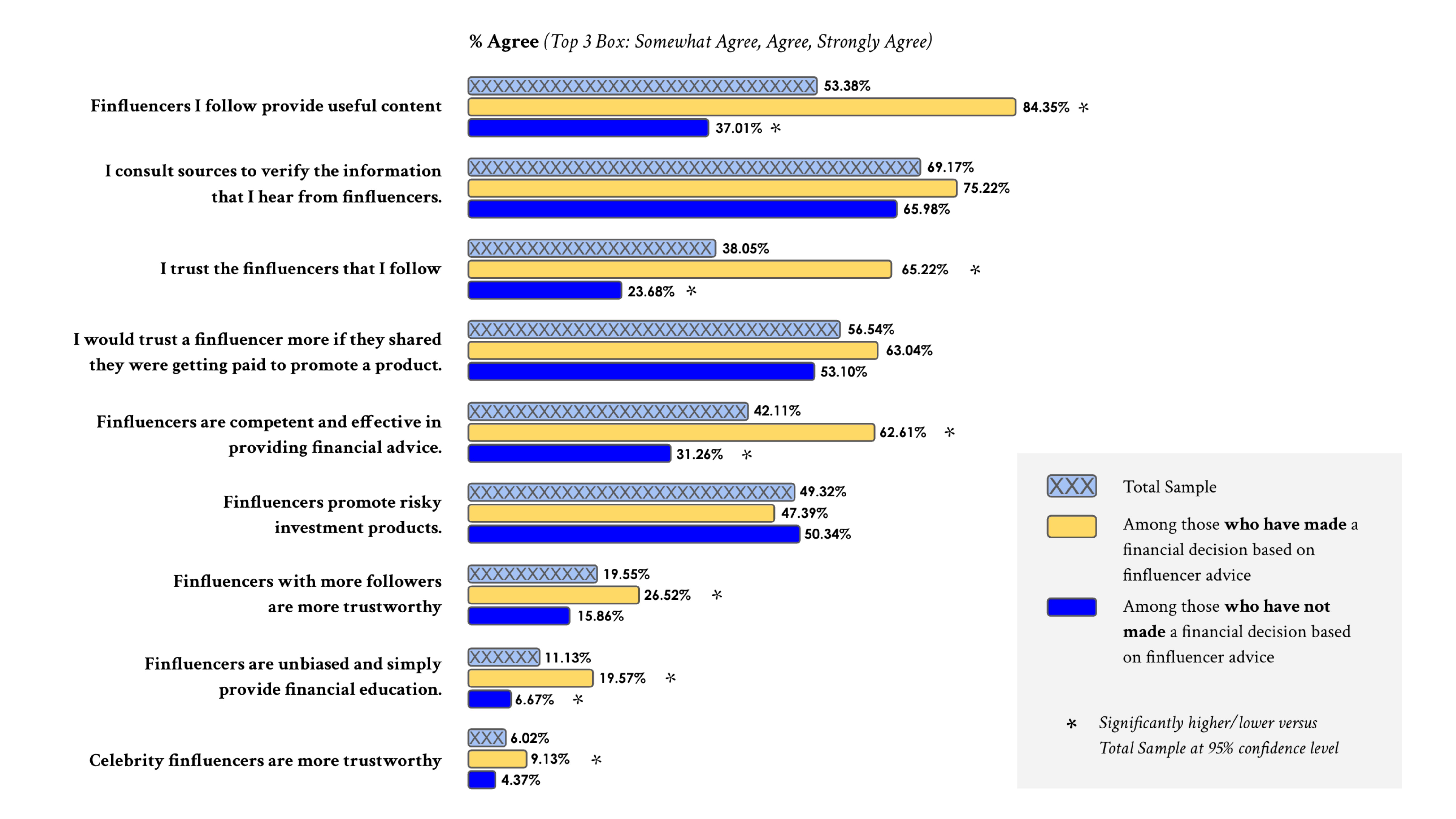

Beyond finfluencer motivations, we asked respondents about their general attitudes and beliefs towards finfluencers (see Figure 8). Our findings indicate that retail investors often believe the finfluencers they follow provide useful and trustworthy content. This appears to contradict earlier results showing that financial advice on social media is generally not trusted. However, our combined results suggest that while investors do not trust social media financial advice in general, they are more willing to trust specific finfluencers with whom they have developed a relationship. Retail investors who have made financial decisions based on finfluencer advice are particularly likely to hold these views. We also observe that many retail investors are inclined to trust finfluencers who provide a disclosure. This is consistent with research in our literature review on consumer perceptions of disclosures of conflicts of interest, which suggest that they can paradoxically build trust[24] and credibility[25], rather than detract from it.

Figure 8. Attitudes Towards Finfluencers

Social Media and Investing Decisions

To conclude our analysis of the survey data, we identified the most powerful predictors of respondents having made financial decisions based on finfluencer advice. Of those who have made financial decisions based on finfluencer advice, they are also more likely to:

- have been scammed on social media (12.2 times more likely).

- trust the financial influencers they follow (7.2 times more likely).

- trade stocks or other investments frequently, several times a week (4.9 times more likely).

- believe the financial influencers they follow provide useful information (3.6 times more likely).

- are willing to take moderate risks and accept some losses to potentially earn higher returns (3.2 times more likely).

- have experienced significant investment losses in the past (2.3 times more likely).

- manage their investments using a self-service mobile app (2.2 times more likely).

Of those who have made financial decisions based on finfluencer advice, they are also less likely to:

- work with a financial advisor or portfolio manager (3.1 times less likely).

- spend less than one hour on social media per day (2.8 times less likely).

Our analysis revealed key predictors for making financial decisions based on finfluencer advice. A history of being scammed on social media, trusting the financial influencers they follow, and frequently trading stocks were the top three predictors for using finfluencer advice for financial decisions. We also found that those who work with a financial advisor or portfolio manager, or spend less time on social media were less likely to use finfluencer advice.

[23] WealthRocket. (2023, July 27). Half of Canadians Turn to Family and Friends First for Financial Advice, Banks a Close Second: WealthRocket Survey. Newswire.ca. https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/half-of-canadians-turn-to-family-and-friends-first-for-financial-advice-banks-a-close-second-wealthrocket-survey-839928927.html

[24] Sah, S., Malaviya, P., & Thompson, D. (2018). Conflict of interest disclosure as an expertise cue: Differential effects due to automatic versus deliberative processing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 147, 127-146.

[25] Sesar, V., Martinčević, I., & Boguszewicz-Kreft, M. (2022). Relationship between advertising disclosure, influencer credibility and purchase intention. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(7), 276.

As the second component of our environmental scan, we analyzed social media posts using an AI (Artificial Intelligence)-based system called Large Language Models (LLM). The purpose of this analysis was to identify the prevalence of persuasive messaging techniques on social media platforms. This analysis provides an additional source of primary data to complement the insights from our literature review and primary data from our retail investor survey, while also enabling us to better replicate social media content in our experiment. The data we extracted is described in Table 3.

Table 3. Extracted Social Media Data

| Platform | Data Type | Number of Posts/Videos |

|---|---|---|

| YouTube | Video transcript, title, description, likes, date, channel, and views. | 454 |

| Post title, content, score, date, user, and subreddit. | 22,749 | |

| X (formerly Twitter) | Tweet content, date, user, and likes | 3,973 |

| TikTok | Video transcript, description, likes, date, user, and views. | 279 |

| Post description, likes, date, and user. | 520 |

We classified the social media content by sending calls to Open AI’s API prompting the large language model (LLM) to classify each post, title transcript, and description. We added an instruction to classify the text based on the concreteness, emotional tone, and persuasion technique used in each of the extracted posts. We used this methodology because LLMs have been shown to be very precise in classifying text in this manner.[26] We incorporate manual oversight into the classification process to ensure accurate execution of the majority of sorting tasks.

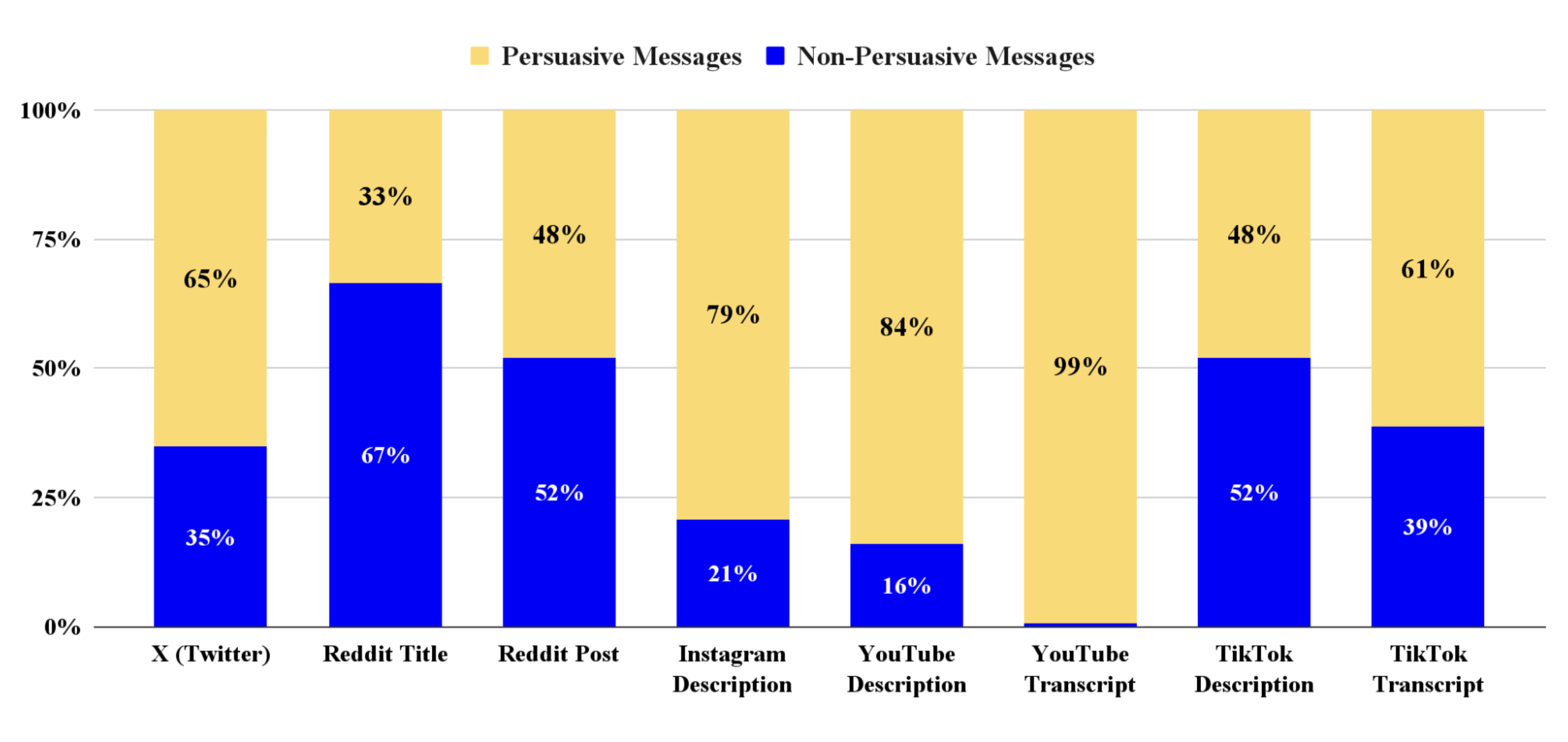

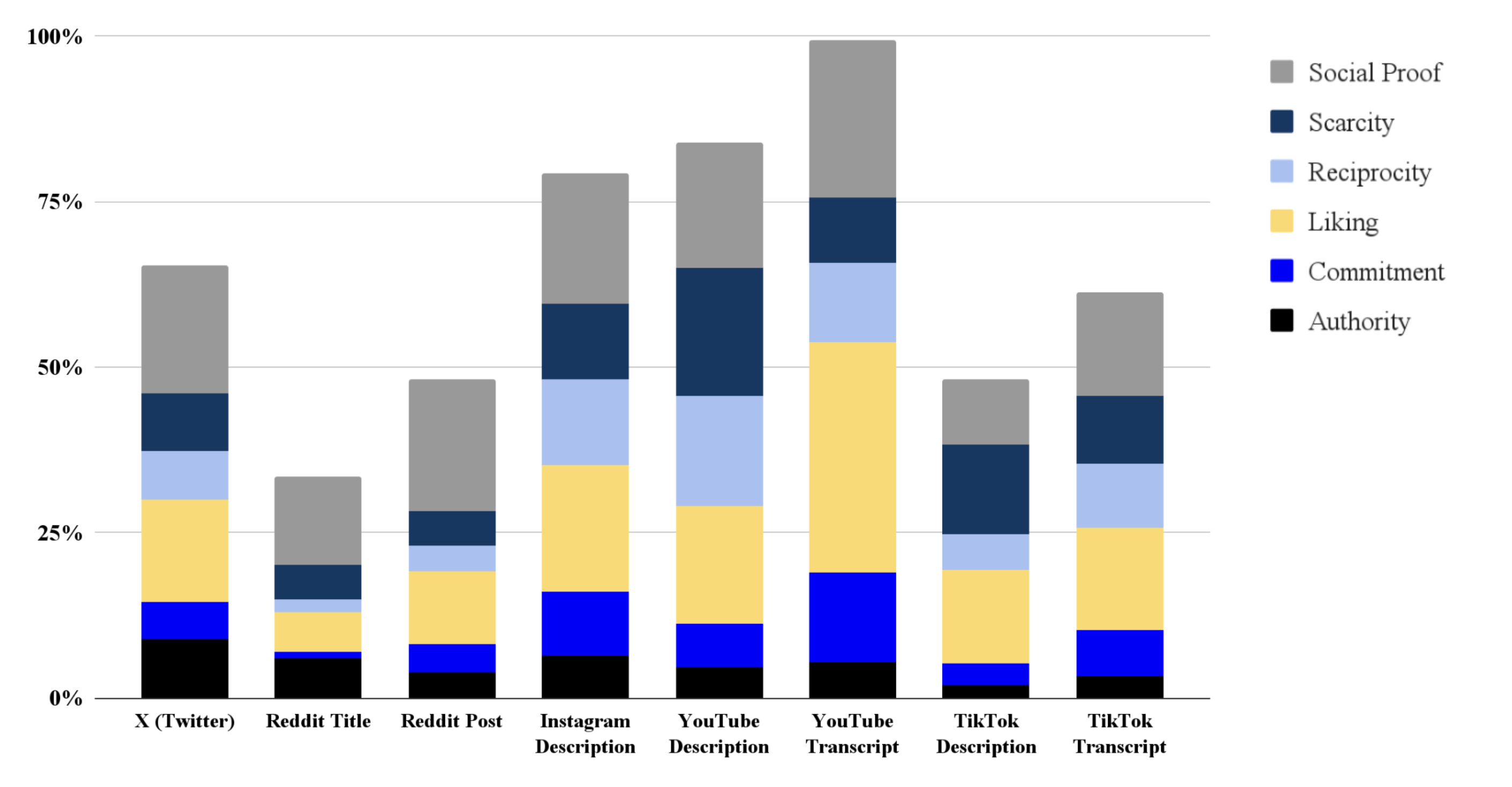

Persuasion Techniques Usage

Our literature review highlighted six persuasion techniques that finfluencers may use to influence their audience.[27] We examined the prevalence of these techniques across the five major social media platforms (see Figure 9). Social proof was found to be the most common persuasion technique across almost all platforms. This method encourages retail investors to follow the actions of others, capitalizing on the human tendency to conform to the behaviour of peers. Liking and reciprocity were also found to be consistently used across platforms. These findings suggest that finfluencer content may involve an interpersonal appeal to followers, while also positioning information as a favour, leaving open the opportunity for followers to reciprocate. Finally, scarcity is a commonly used technique which may be used to motivate action at the expense of careful consideration of the quality of investment opportunities.

Figure 9. Persuasive Messages and Techniques by Platform

To be categorized as a “persuasive message” the piece of content must have been identified as containing at least one example of the six persuasion techniques explored.

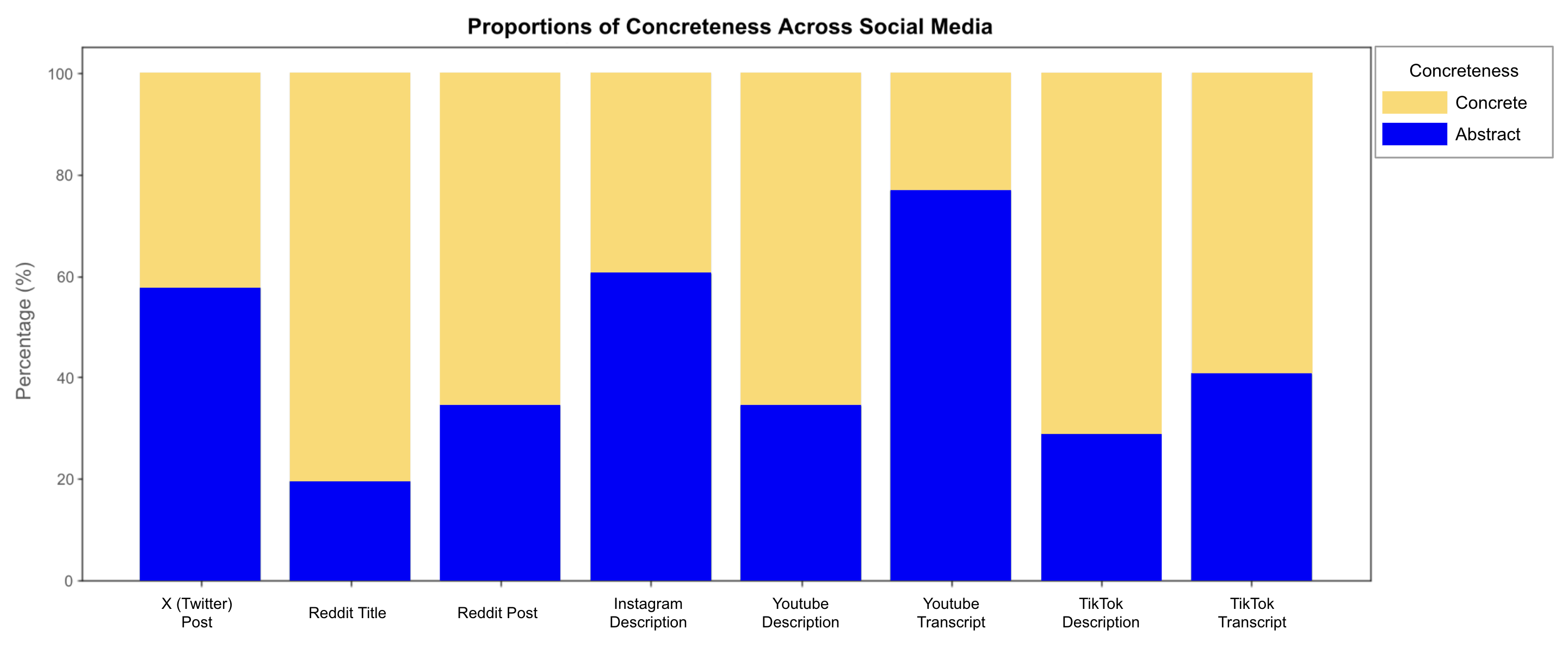

Concreteness and Emotional Tone

In addition to the persuasion techniques, our literature review also examined concreteness and emotional tone. Recall that messages characterized as more concrete are generally perceived as more credible and actionable than those identified as more abstract.[28] Through our analyses of the scraped data, we identified the proportion of social media posts coming from five social media platforms (see Figure 10). Reddit and TikTok were found to have the largest proportion of concrete messages, and therefore we might speculate that the messages on these platforms could be perceived as more credible and more likely to be followed. In contrast, YouTube videos (analyzed by their transcripts) were found to have fewer concrete messages, suggesting that they may be perceived as less credible compared to content from other platforms. This may be relevant to the finding from our survey that instances of scams are relatively less common on YouTube, as a scam will generally focus on encouraging a specific action, and thus benefit from more concrete messaging.

We also note a consistent trend across platforms whereby post titles or descriptions tend to include more concrete messages than the corresponding post or video itself. Given that titles and descriptions are often intended to drive engagement with the content, it is plausible that finfluencers have identified these as effective methods for driving engagement.

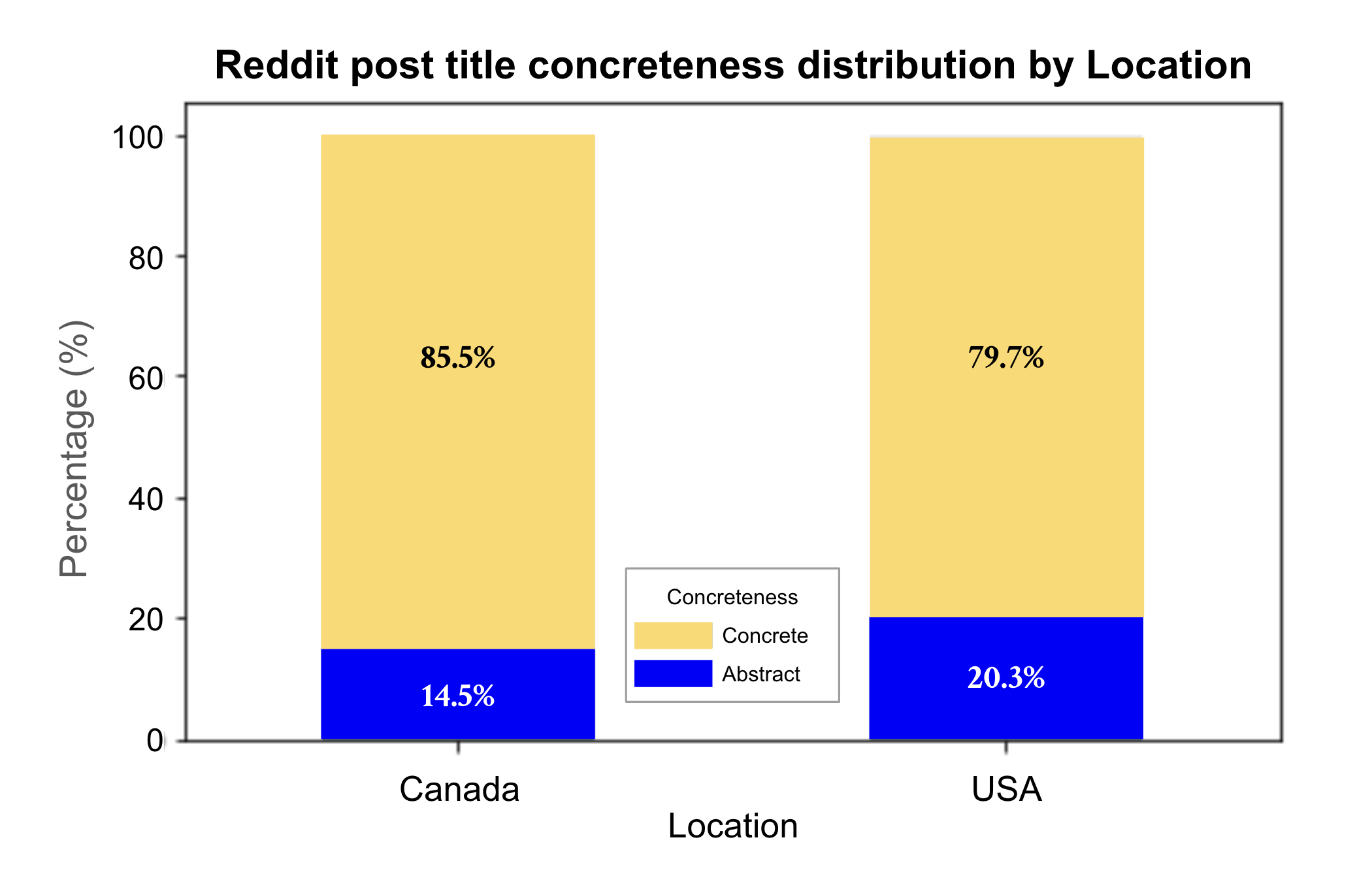

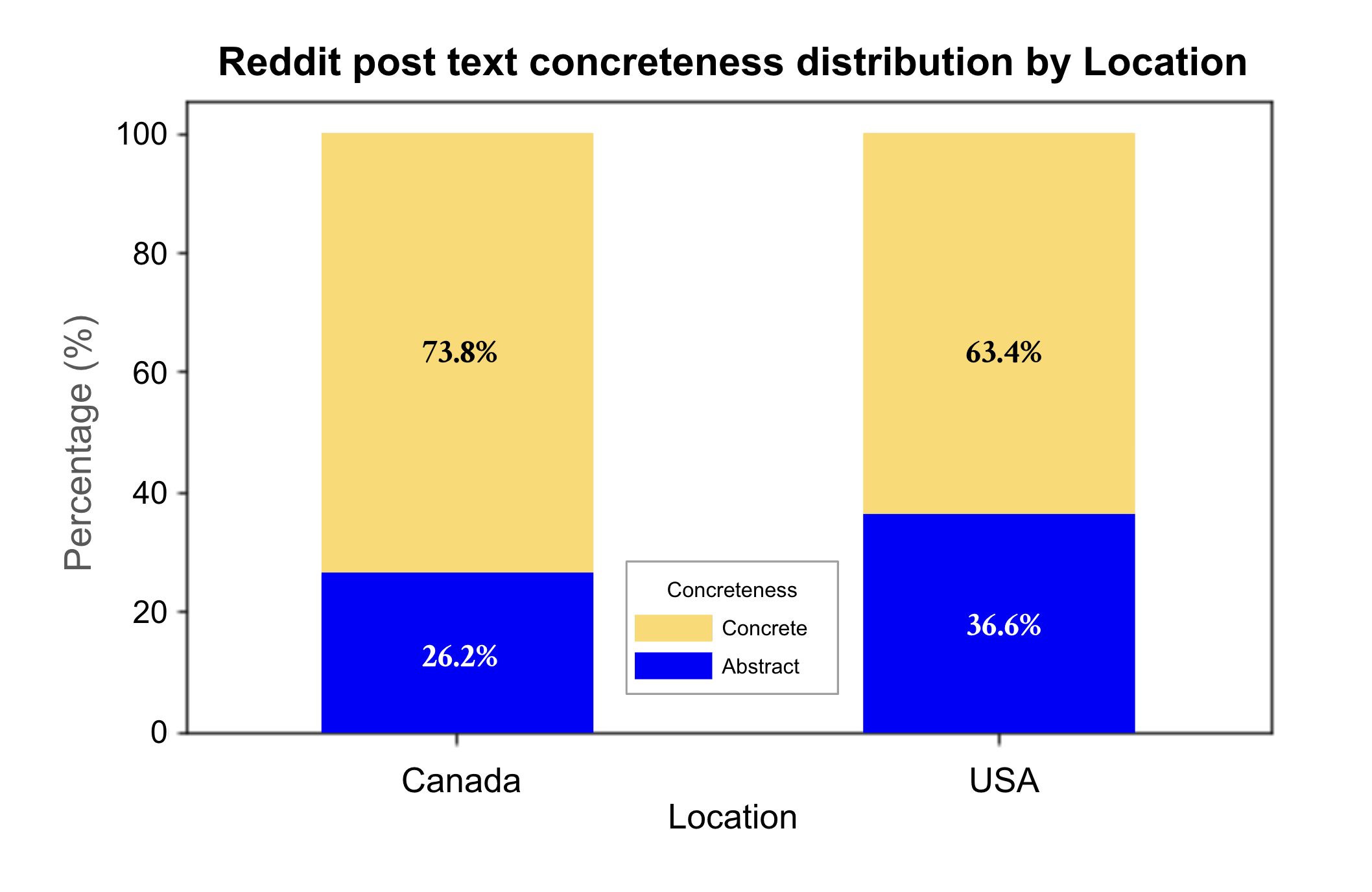

Figure 10. Message Concreteness Classification by Platform

Upon examining Reddit posts categorized by location, we found that posts in Canada exhibit more concrete messaging compared to those from the United States (see Figure 11). This finding is consistent across both the titles and content of posts, indicating that Canadian finfluencers may be leveraging these strategies more frequently than their American counterparts.

Figure 11. Reddit Concreteness Classification in Canada and USA

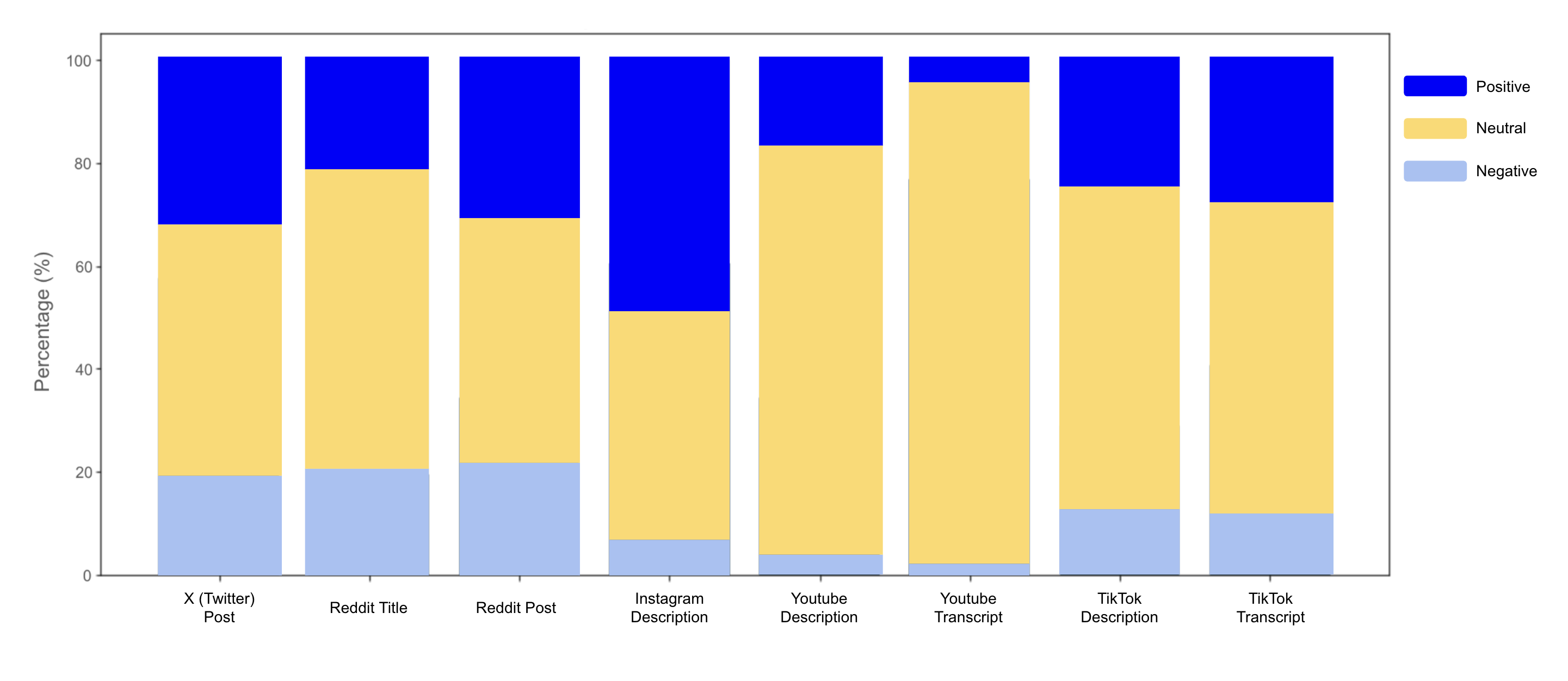

In our literature review, we also identified emotional tone as an important characteristic of messages in that negative information spreads more rapidly.[29],[30],[31] Our data extraction allowed us to examine the emotional tone of messages across these same five platforms (see Figure 12). Reddit and X (formerly Twitter) were found to have the highest percentage of negative emotional tone content. In contrast, Instagram and YouTube had the highest percentage of positive emotional content.

Figure 12. Emotional Tone Classification by Platform

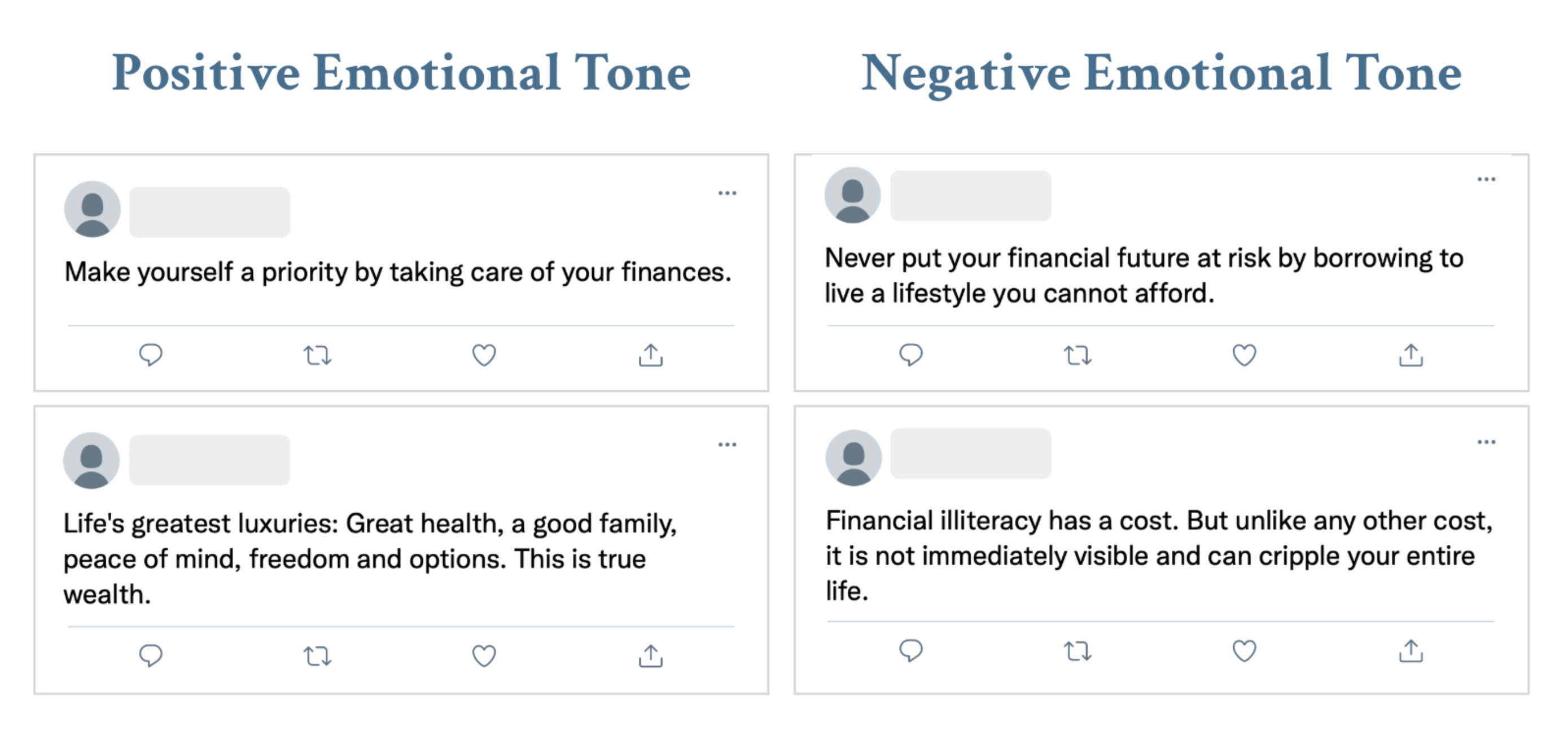

Figure 13 provides examples of real Tweets with positive and negative emotional tones drawn from our analysis. Messages on the left are categorized as having positive emotional tone as they paint a positive picture of well-being through the lens of financial responsibility. Conversely, messages on the right take a negative, cautionary tone that emphasizes the gravity of potential consequences of financial illiteracy or actions like borrowing money. The deliberate use of strong language, such as “put your financial future at risk”, may instill a sense of fear or anxiety among recipients.

Figure 13. Examples of Positive and Negative Tones

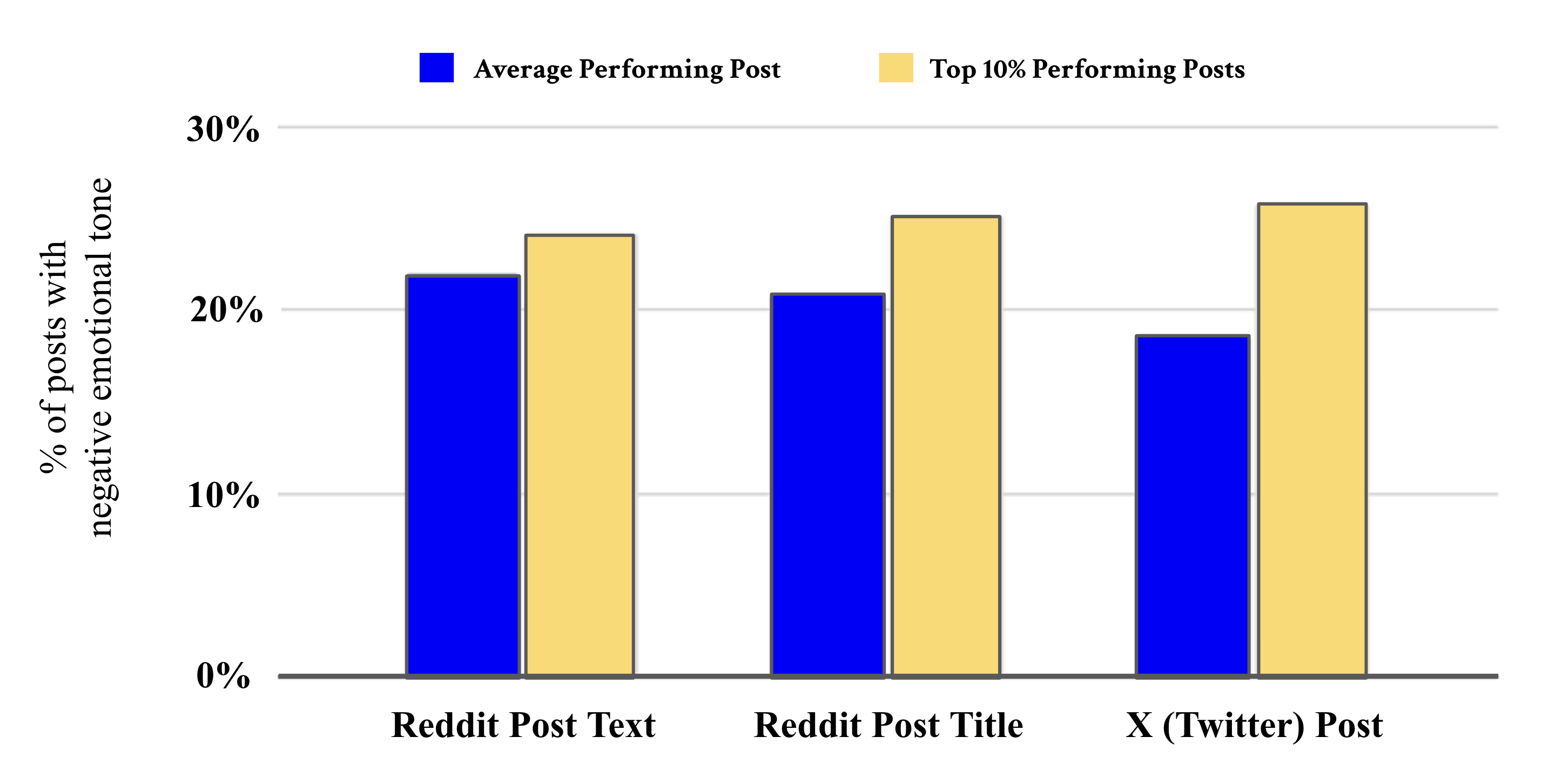

When exploring the use of negatively charged messages across Reddit and X, we see that the most successful posts (assessed by engagement metrics such as upvotes or likes) tend to be more negative (see Figure 14). This is consistent with evidence from our literature review stating that negative information tends to spread more widely.

Figure 14. Negative Emotional Tone in Top Posts of Reddit and X

In sum, we find evidence of persuasive messages being deployed across social media. Our findings indicate that finfluencers are deploying strategies—whether intentionally or inadvertently—capable of influencing the behaviour of retail investors. Taken together with the findings from our retail investor survey, we find that:

- Persuasion strategies that can reasonably be assumed to influence retail investors are prevalent across financial social media content.

- Having made financial decisions based on finfluencer advice is correlated with a history of being scammed on social media, trusting finfluencers, and more frequent trading.

- Lower levels of engagement on social media platforms and working with a financial advisor are both associated with a decreased likelihood of making financial decisions based on finfluencer advice.

[26] Rickard, M. (2023, July 10). Categorization and Classification with LLMs. Matt Rickard. https://blog.matt-rickard.com/p/categorization-and-classification

[27] Cialdini, R. B., & Cialdini, R. B. (2007). Influence: The psychology of persuasion (Vol. 55, p. 339). New York: Collins.

[28] Balaji, M. S., Jiang, Y., & Jha, S. (2021). Nanoinfluencer marketing: How message features affect credibility and behavioral intentions. Journal of Business Research, 136, 293-304.

[29] She, J., & Zhang, T. (2019). The impact of headline features on the attraction of online financial articles. International Journal of Web Information Systems, 15(5), 510-534.

[30] Tsugawa, S., & Ohsaki, H. (2015, November). Negative messages spread rapidly and widely on social media. In Proceedings of the 2015 ACM on conference on online social networks (pp. 151-160).

[31] Hornik, J., Satchi, R. S., Cesareo, L., & Pastore, A. (2015). Information dissemination via electronic word-of-mouth: Good news travels fast, bad news travels faster!. Computers in Human Behavior, 45, 273-280.

Experiment

Experiment

The final component of our research consists of an online randomized controlled trial (RCT). In our experiment, we explored two questions:

- What is the influence of financial information from social media on investment decisions?

- How can interventions modify the effect of financial information on investment decisions?

With respect to the first question, our experiment evaluates the effects of social media on financial decision making in an environment that closely resembles a real-world trading environment. With respect to the second question, our experiment investigates the influence of several interventions—disclosure, prebunking, inoculation, and nudges—in modifying the impact of financial information on decision-making. We conducted the survey from October 30 to November 13, 2023.

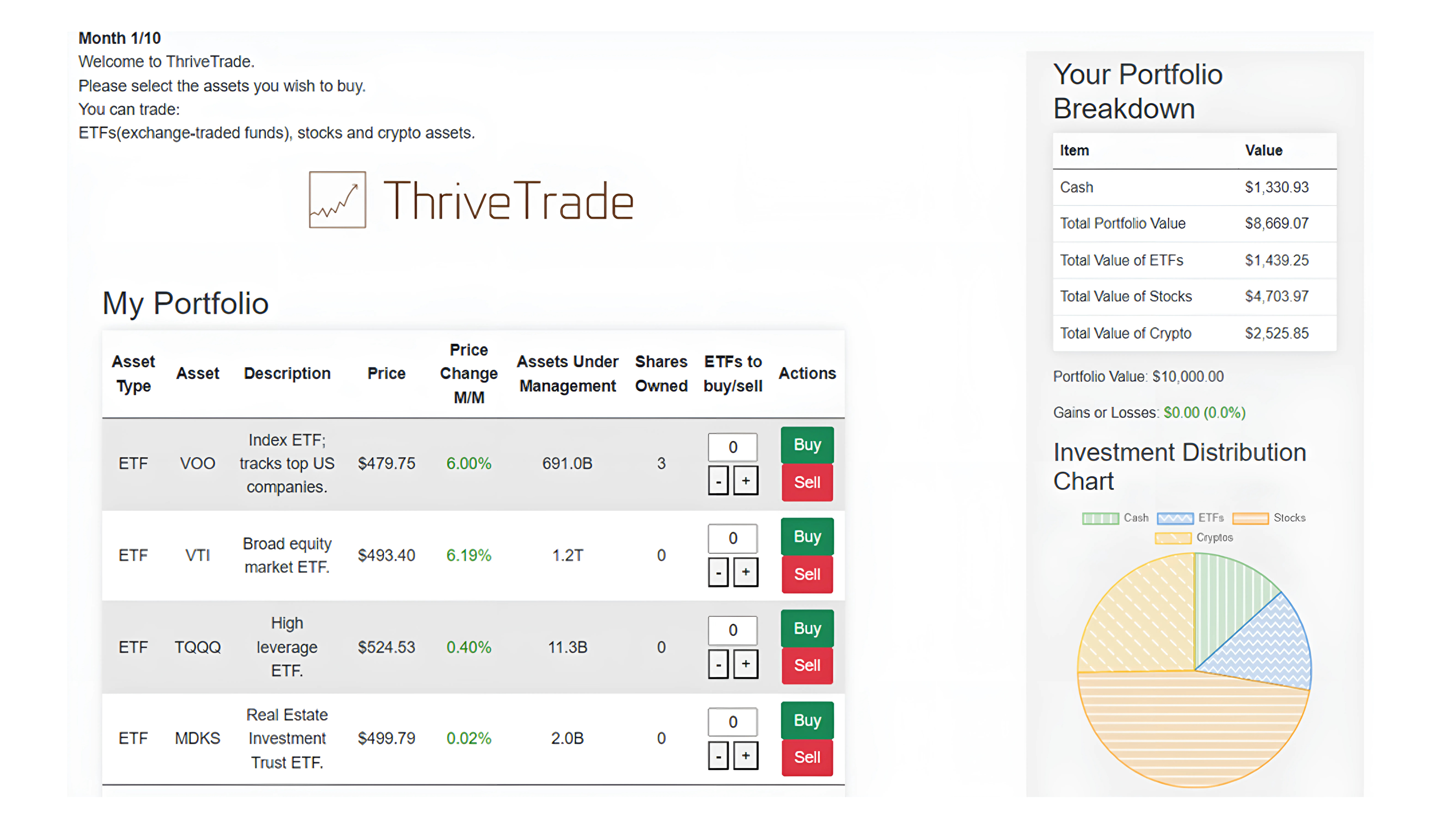

Participants undertook a trading simulation consisting of 10 rounds. During each round, participants could trade a variety of assets drawn from three classes: individual stocks, ETFs, and crypto assets. Asset prices were based on real-world historical data. For each asset, we took the price from the periods Q1 2021 to Q2 2023. Each quarter represented a month's worth of price movements in our experiment. We did this to reduce variance and more accurately track the trajectory of the reference asset. We also normalized the prices of assets in our experiment to be roughly $500. This was done to simplify the experience for participants, as well as to mask the identity of reference assets with potentially recognizable price points (e.g., Bitcoin). Some assets had real names, whereas others were fake but seemingly real.

Participants made trades through the trading interface (Figure 15). Participants were given an initial “balance” of a simulated $10,000 in their accounts and were told that their goal was to maximize returns over the 10 rounds. Participants were paid to participate in the experiment, and a bonus was awarded to top performers to provide an incentive to maximize returns.

Figure 15: Experiment Trading Interface

Social Media Posts

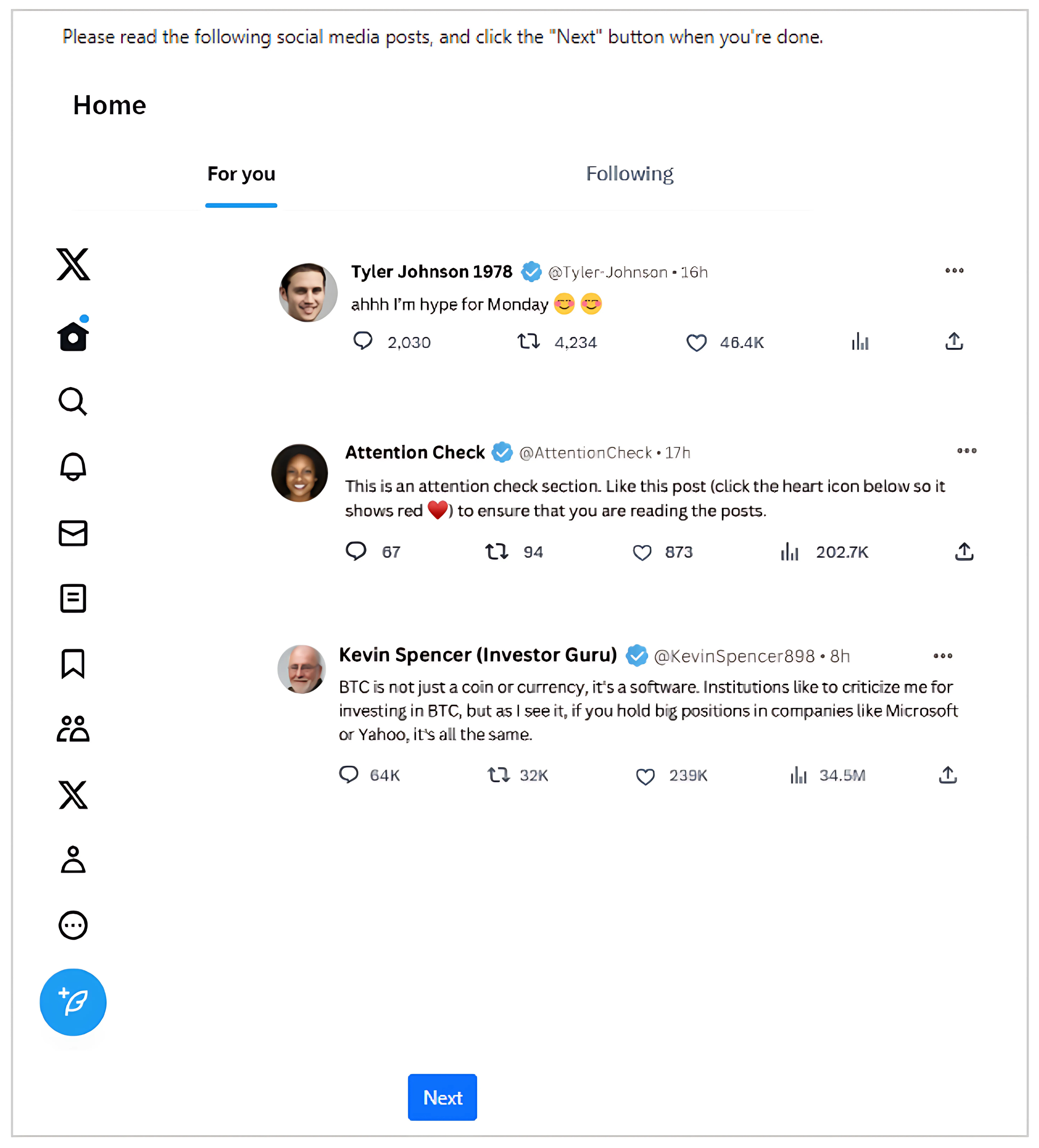

To better understand the influence of social media content on trading behaviour, we exposed participants to a range of social media posts in between certain rounds of trading. The posts we showed participants were inspired by posts identified in our environmental scan. However, the associated usernames and content were adjusted. Six different social media posts were shown to participants, reflecting content found on X, Reddit, and YouTube. These posts were designed to promote a particular asset within the experiment. Figure 16 shows the interface for X for the experiment arms which contain the social media stimuli.

Figure 16: Social Media Interface

Experiment Conditions

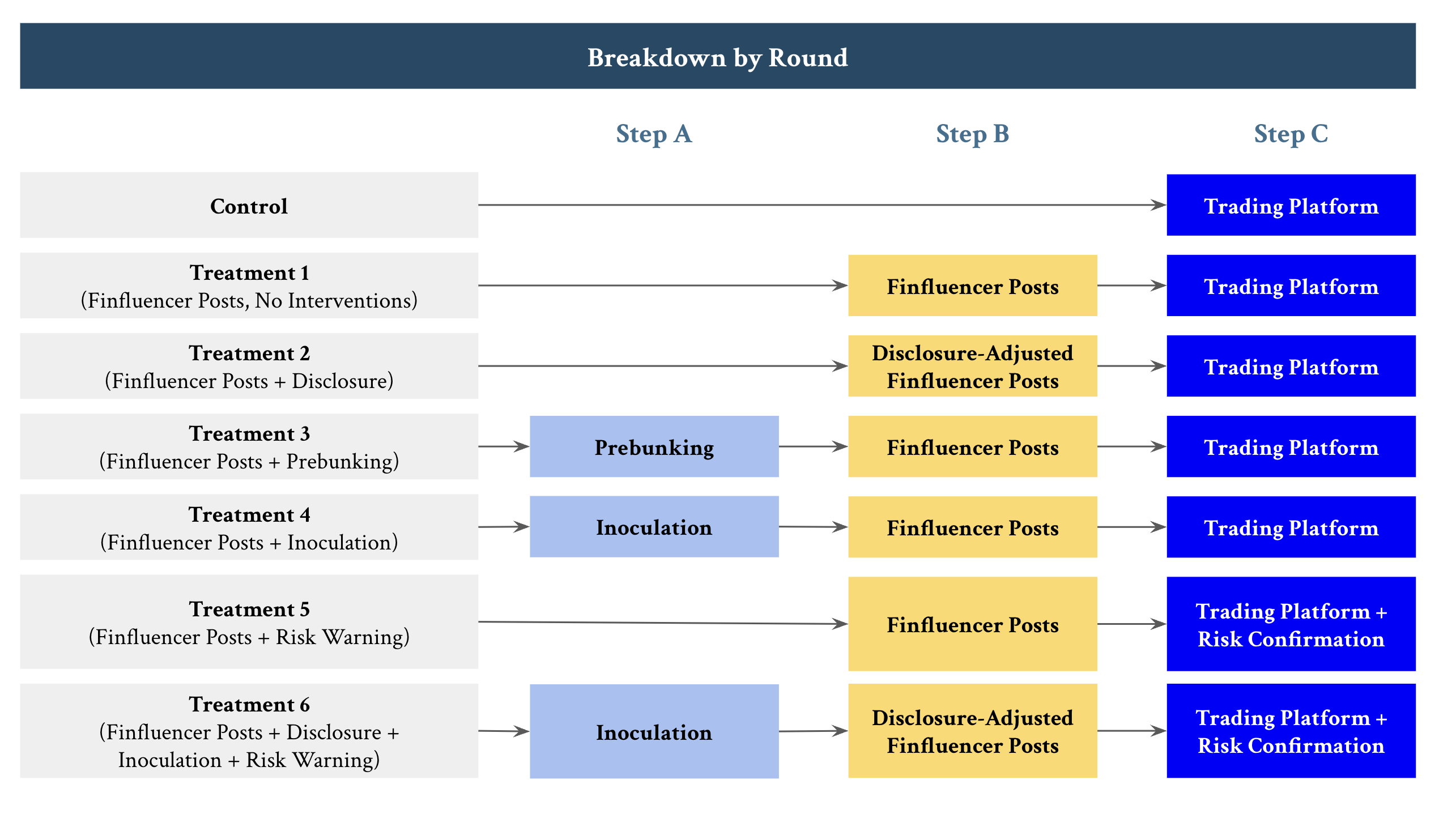

A total of 1,465 participants were randomly assigned to one of seven experiment conditions, as outlined below.

Table 4: Overview of Experiment Conditions

Experiment Condition | Finfluencer Posts ✓=Present X=Absent | Intervention | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

Control | X | None | Participants were shown generic social media posts unrelated to finance. |

Treatment 1 | ✓ | None | Participants were shown a social media feed containing a post promoting a particular asset for each of the six social media rounds. |

Treatment 2 | ✓ | Disclosure | A disclosure was added to each finance-related social media post. The message warns the user of potential biases and conflicts of interest in the post. |

Treatment 3 | ✓ | Prebunking | A prebunking message is placed as an additional post preceding each finance-related social media post. The message alerts the user of misleading content on social media. |

Treatment 4 | ✓ | Inoculation | An inoculation precedes each finance-related social media post. The message illustrates an example of misinformation on social media and explains the flaws. |

Treatment 5 | ✓ | Risk Warning (Nudge) | When purchasing stocks or crypto assets, participants were shown a message outlining the risks associated and asked for confirmation before proceeding. |

Treatment 6 | ✓ | Disclosure Inoculation Risk Warning (Nudge) | Participants are shown the inoculation and disclosure interventions in the social media feeds. The risk confirmation message is also present on the trading platform. |

Figure 17 illustrates the procedure for each group of participants in the experiment.

Figure 17: Experiment Procedure

The first three treatment groups received disclosure, prebunking, or inoculation interventions, respectively.

- Disclosure: A message that reveals or discloses information about potential biases, conflicts of interest, or persuasive intent behind the communication.

- Prebunking: A message that aims to pre-emptively expose and counteract misinformation or biased perspectives before the audience encounters them.

- Inoculation: A message that introduces a weak form of an argument or misinformation to 'inoculate' the audience, making them more resistant to persuasion in the future.

For all three of these conditions, each social media stimulus promoting a specific asset was coupled with an intervention. Table 5 provides an example of an intervention within each treatment group. Our disclosures were displayed as if it came directly from the social media platform. This choice was made to explore whether a disclosure originating from the platform limits the documented effect of increasing the perceived credibility of the messenger. Our prebunking and inoculation interventions is posted from a fictitious regulator social media account.

Table 5. Variations of Interventions on X

Intervention Type | Intervention Post |

|---|---|

Disclosure |

|

Prebunking |

|

Inoculation |

|

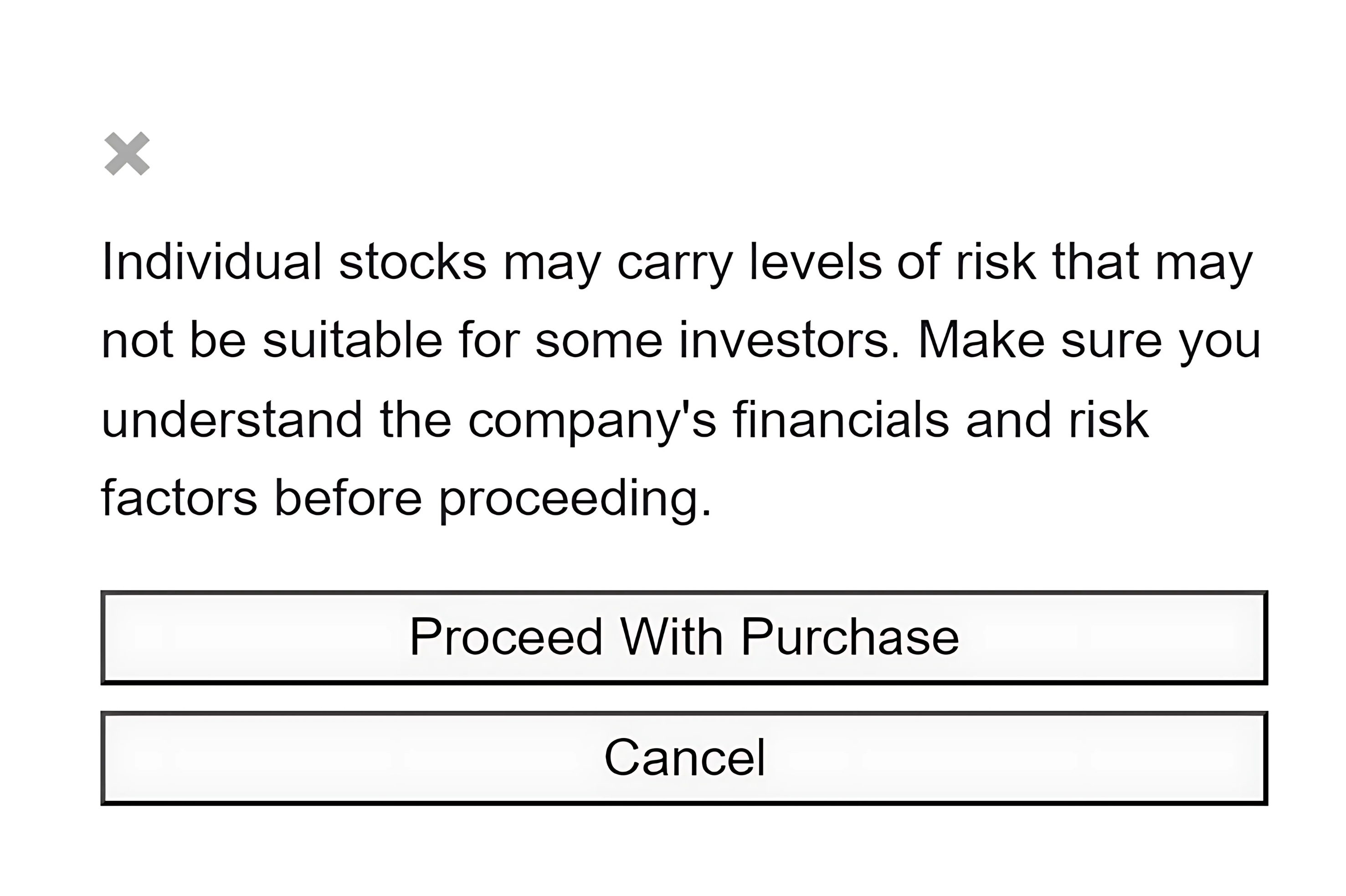

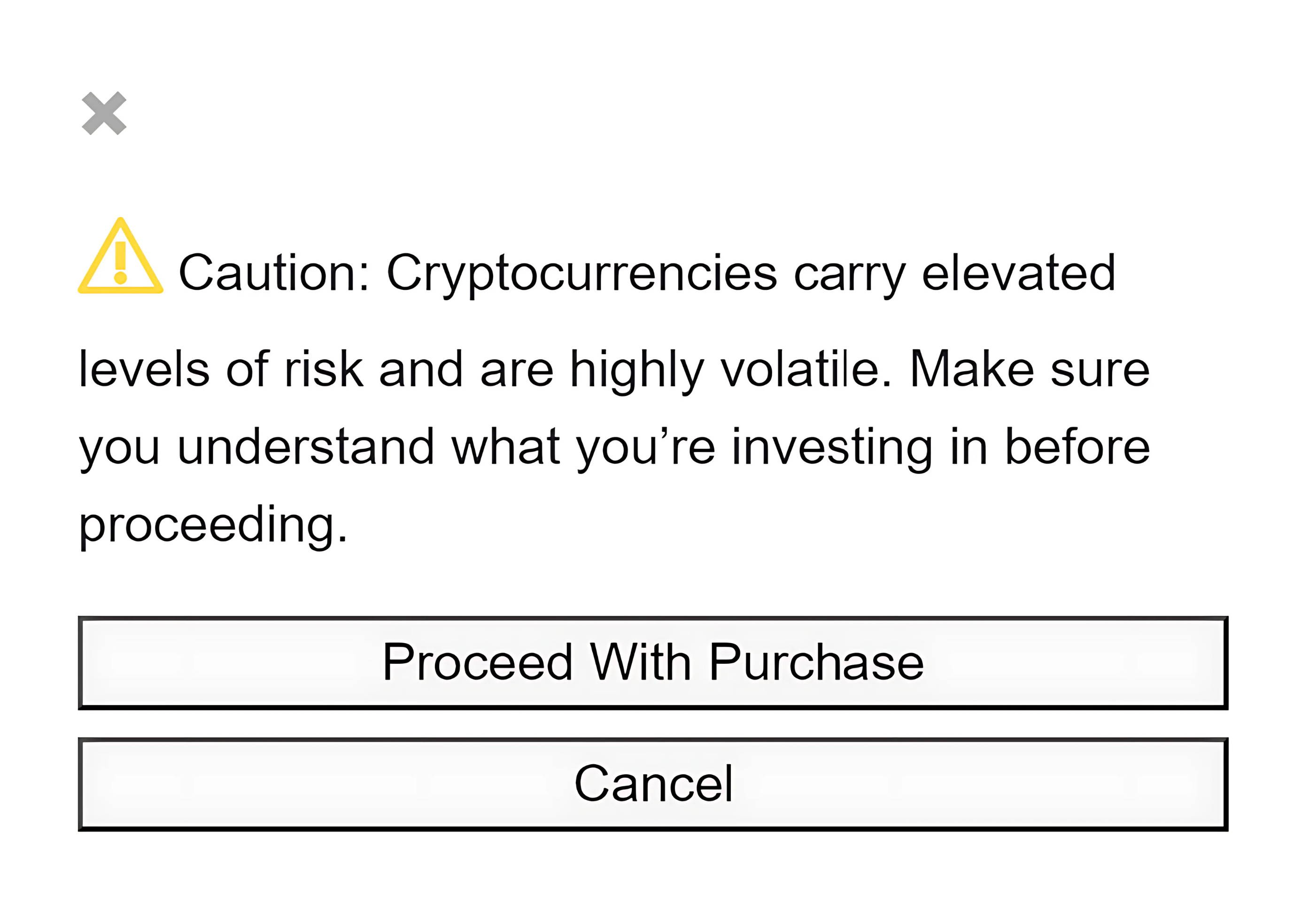

The fourth treatment group differed from the other three as participants engaged with a slightly modified version of the trading platform. The platform was almost identical to other conditions, except in that participants would need to click through a warning message if they attempted to purchase higher risk assets (i.e., cryptocurrencies or high-volatility stocks). They were then allowed to readjust their trading order before proceeding (Figure 18). The warning message was shown at maximum once per round—the first time a participant attempted to make a trade. We hypothesized that additional warning messages per round may disproportionately discourage participants to trade.

Figure 18: Risk Confirmation Messages

Stock risk confirmation message | Crypto asset risk confirmation message |

|---|---|

|  |

Finally, to ensure data quality, two attention checks were included in the experiment. These attention checks were questions and tasks embedded within the experiment to verify that respondents were reading and paying attention to the social media posts.

A total of 2,008 Canadian social media users were recruited to participate in our experiment. 27% failed both attention checks, resulting in a final sample of 1,465 included in our analysis. An attention check failure rate of 27% is quite high, and is perhaps attributable to the unconventional attention check format. That said, we deemed it important to verify that the social media posts were being read to ensure high quality data.

Participants in our experiment skewed women (57% vs 43% men). Our sample also trended younger, with the majority of respondents being between the ages of 18 and 35. The ethnic distribution of our sample was comparable to nationwide demographic data. While most respondents were white, 55% is less than the reported 70% of Canadians who identify as white. Asian respondents were overrepresented in our experiment (28%) relative to national data. Among our eligible participants, 59% were classified as retail investors (41% non-investors).

Trading Promoted Assets

The social media posts integrated into our simulated experience were designed to promote specific assets within the experiment. In light of this, our primary outcome of interest was the proportion of participants who purchased at least one share/coin of the promoted asset in the following round (after being exposed to the social media post promoting the asset).

24% of participants who were exposed to the finance-related social media posts, without any intervention, purchased the promoted assets. Conversely, only 7% of participants who did not see finance-related posts purchased the promoted assets. As the experience was otherwise identical, we can conclude that exposure to a social media post caused investors to purchase certain assets. This provides clear evidence that social media content can influence the decisions made by retail investors.

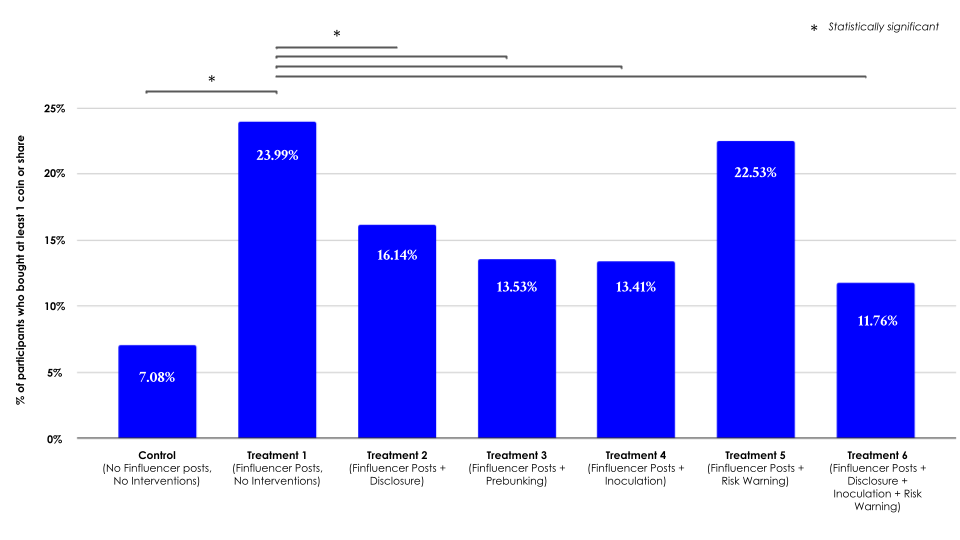

Figure 19: Trading of Promoted Assets by Condition

At a glance: Finfluencer posts significantly increased the trading of promoted assets. All mitigation techniques were effective except for when only the risk confirmation message was used.

Having established this effect, we then looked at the ability of our interventions to mitigate the influence of social media posts on trading behaviour. We found evidence that our disclosures, prebunking, and inoculation interventions reduced the proportion of participants who purchased the finfluencer-promoted assets, suggesting that these interventions can protect investors from social media-driven influence, albeit to varying degrees (see Figure 19).

Our nudge intervention, which integrated a warning directly into the trading platform, did not have any effect on the proportion of participants who purchased the promoted assets. Although the warning message had no material impact in our experiment, this does not necessarily imply that warnings are ineffective. Factors such as wording, frequency, location, and the trust a user places in the provider of the warning could influence the effectiveness of this type of intervention.

The experimental condition that included a disclosure, inoculation, and a warning message performed similarly to conditions in which only one intervention was provided, suggesting that there is no additional value in combining our interventions. This may mean that one intervention (inoculation) has already reached its maximum effect to reduce the influence of finfluencers, so adding other methods does not make a difference.

Finally, we note that none of these interventions fully mitigated the influence of social media posts. Approximately twice as many investors in our prebunking and inoculation conditions purchased the finfluencer-promoted asset than those in our control group. Therefore, while our interventions were effective at reducing the persuasiveness of social media content, they do not eliminate the influence of social media messaging entirely.

Platform Specific Effects

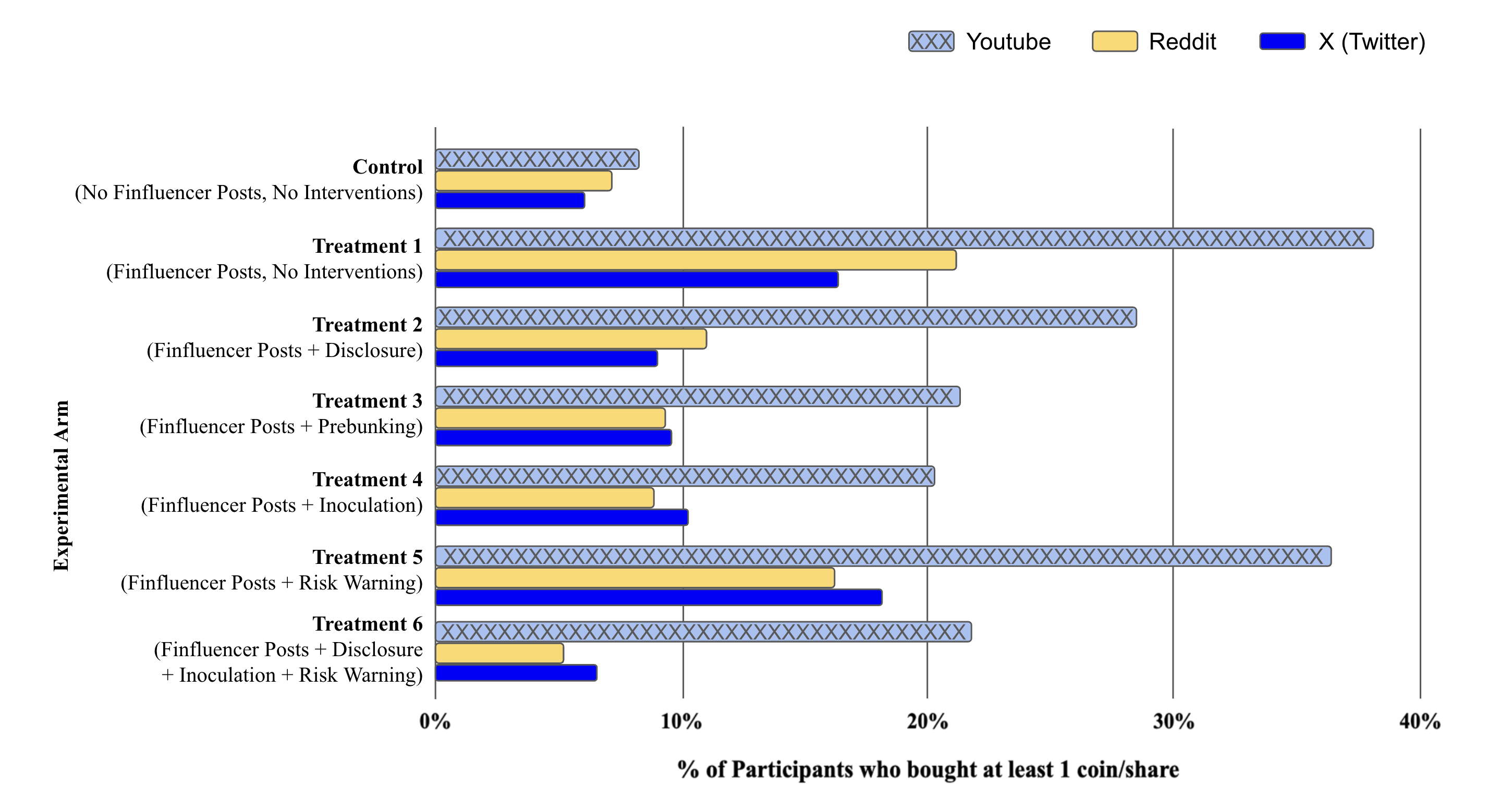

Further analysis of our data showed that social media platforms influenced participants to varying degrees (Figure 20). Video content, depicted as being delivered through YouTube, influenced investor decision-making to a higher degree than content from Reddit or X. While the effectiveness of interventions for video content was directionally similar to other forms of communication, with disclosure, prebunking, and inoculation countering the impact of these messages, video content appears to be more persuasive than messages delivered through Reddit or X. This finding is consistent with existing research illustrating that video content on social media is generally more persuasive than text-based content.[32] As our interventions were not adapted to the format of the social media post, it is possible that mitigation messages delivered through video would exert an even greater influence.

Figure 20: Trading of Promoted Assets by Platform

At a glance: Finfluencer posts on YouTube were far more effective in encouraging trading than posts on other platforms.

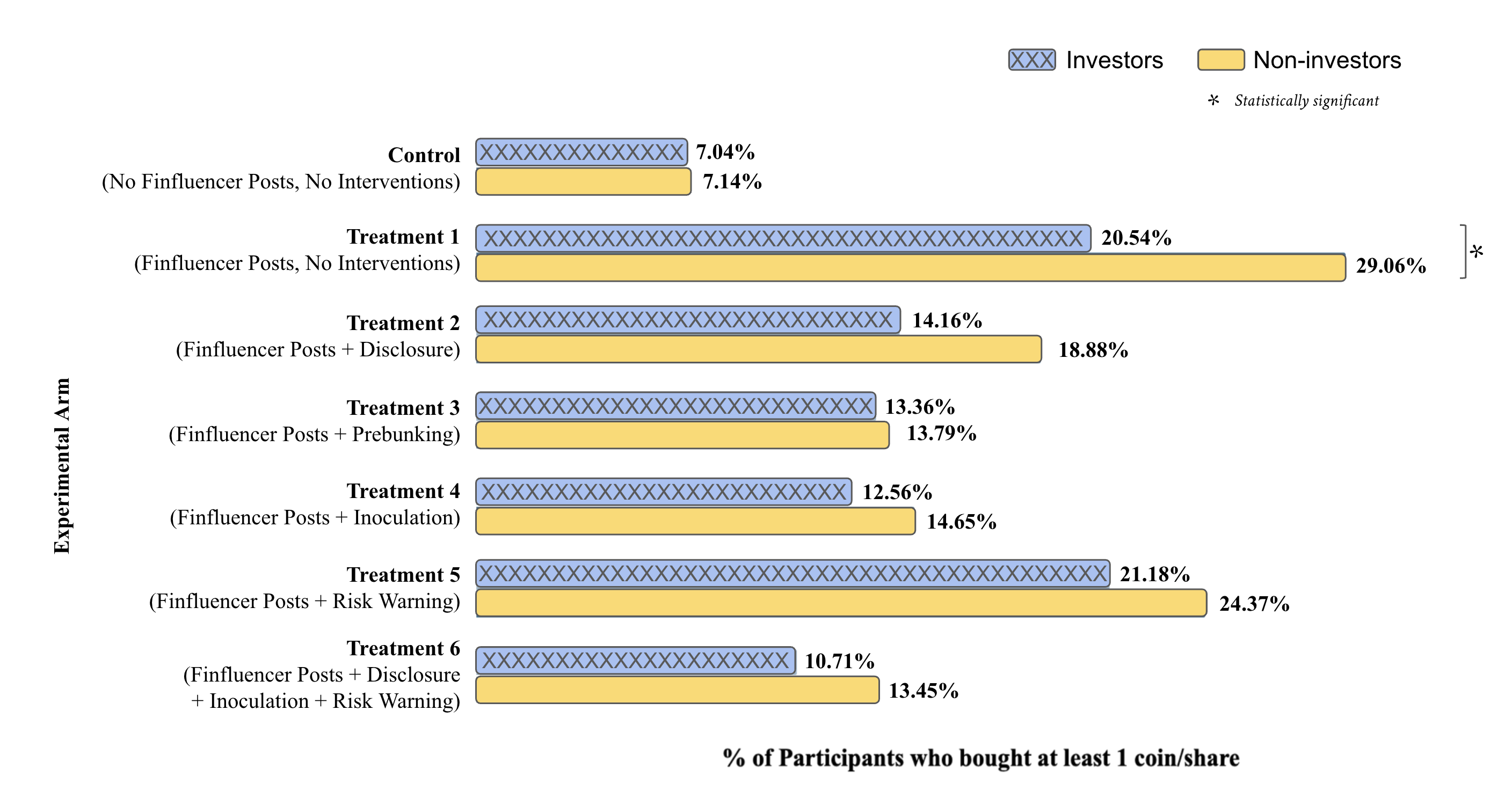

Non-Investors Trading Behaviour

We performed a separate analysis to explore any differences between current retail investors and non-investors. This analysis was conducted to understand whether less experienced individuals (non-investors) are more susceptible to finfluencer messaging than relatively more experienced investors. In our control group (no finance-related posts), trading behaviour was similar between investors and non-investors (Figure 21). We do, however, see differences in the presence of finance-related social media content. When exposed to finance-related social media content, 21% of investors purchased the asset promoted in a post, compared to 29% of non-investors. This difference was statistically significant, suggesting that non-investors are at an elevated risk of being influenced by finfluencer content on social media.

We also identified trends in our data to suggest that our interventions are more effective at mitigating the persuasive effects of social media on non-investors. The difference in trading behaviour between investors and non-investors in our control group disappears following exposure to any of our interventions. The prebunking and inoculation conditions were particularly effective at equalizing the proportion of investors and non-investors who purchased the promoted assets. These results indicate that non-investors are more likely to be persuaded by financial information on social media, but also that they may disproportionately benefit from interventions intended to protect them from influence. Employing these strategies could provide significant benefit to new investors who are at greater risk of finfluencer persuasion.

Figure 21. Trading of Promoted Assets: Investors vs Non-Investors

At a glance: Finfluencer posts were more influential on non-investors compared to investors.

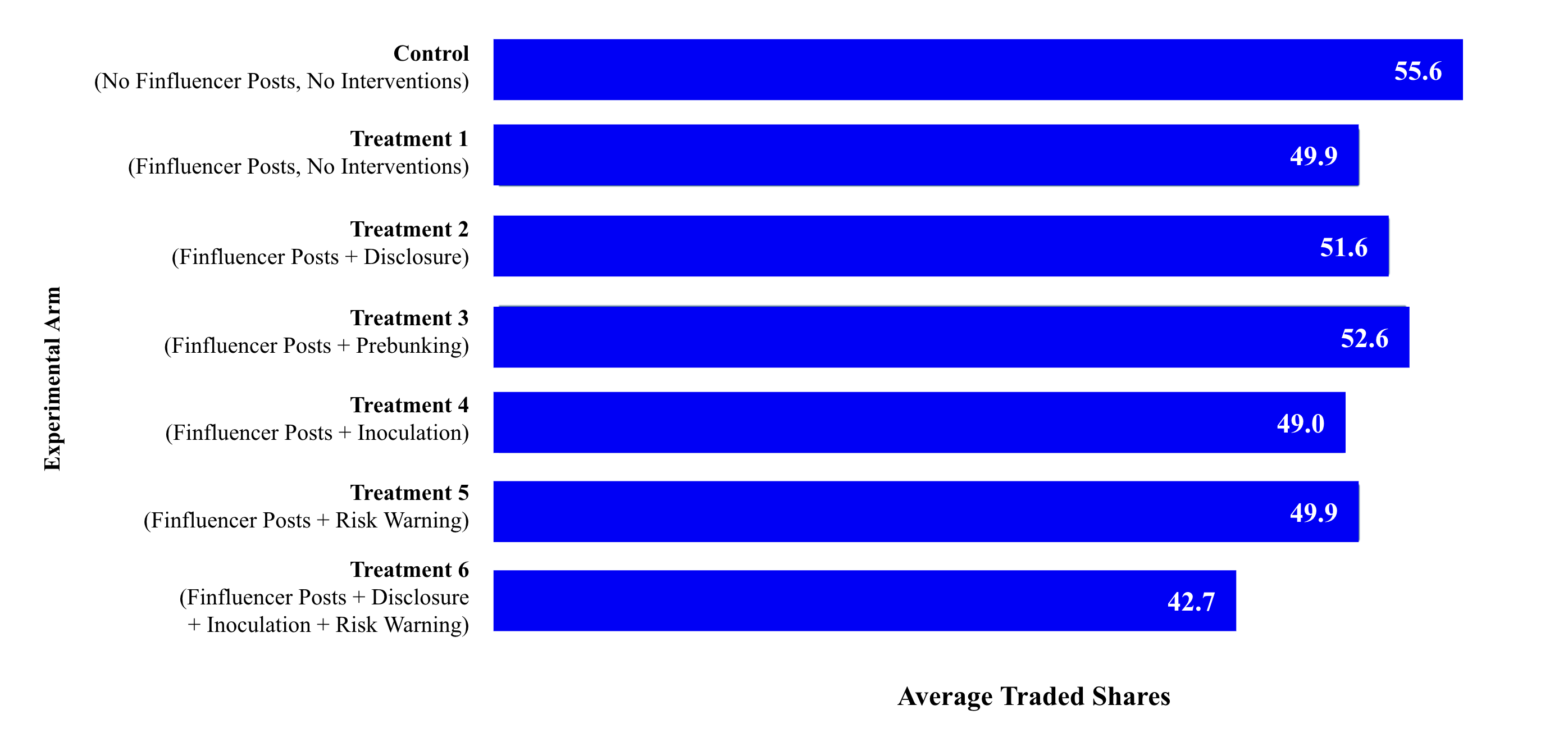

Trading Volume

A further goal of our analysis was to understand the effects of finance-related social media posts on trading volume, as previous research has demonstrated that increased trading volume is associated with lower returns in the long run.[33] In doing so, we analyzed the average number of traded shares made by participants in each condition of the experiment (Figure 22). We do not observe any meaningful difference in trading volume among any of our conditions. Considering the primary findings of our experiment, this suggests that while finfluencer content may focus trading activity on specific assets, it does not appear to affect overall trading volume.

Figure 22. Trading Volume by Condition

At a glance: There were no meaningful differences in trading volume among any of our conditions.

[32] Mohammadi, G., Park, S., Sagae, K., Vinciarelli, A., & Morency, L. P. (2013, December). Who is persuasive? The role of perceived personality and communication modality in social multimedia. In Proceedings of the 15th ACM on International conference on multimodal interaction (pp. 19-26).

[33] Barber, B. M., & Odean, T. (2000). Trading is hazardous to your wealth: The common stock investment performance of individual investors. Journal of Finance, 55(2), 773-806.

In this work we surveyed retail investors, analyzed content from social media, and conducted a randomized controlled experiment. We have identified several novel findings:

- Of the surveyed Canadian retail investors, 35% have made decisions based on financial advice from a finfluencer. Individuals who have made such a decision are also more likely to have a history of being scammed on social media, have a higher level of trust in finfluencers they follow, and engage in more frequent trading.

- Content featured on social media platforms frequented by Canadian investors often incorporate persuasion elements. This holds true across all social media platforms examined although they differ on the degree to which they contain persuasion techniques.

- The persuasion elements found in certain social media content may influence the decisions of retail investors in the context of a trading simulation. They do so by driving the purchase of specific assets which are promoted by finfluencers. This risk is heightened for new and inexperienced investors.

- Certain messaging interventions—disclosure, prebunking, and inoculation—can help mitigate the persuasive impact of finfluencer posts on investor decision-making, as seen through a reduction in purchasing of promoted assets. However, we note that none of these interventions fully mitigated the influence of social media posts.

Conclusion

Conclusion

From the perspective of retail investors, financial advice found on social media can be appealing. It is accessible, free, and can be informative. However, the quality of financial advice on social media varies widely, and our research uncovers several concerning findings with respect to the impact of social media on retail investors.

Our analysis of social media content shows that many finfluencer posts contain persuasion techniques such as social proof, scarcity, reciprocity, and liking. Finfluencers often use more concrete messaging, which can increase the credibility of messages. Their messages can often also carry a negative emotional tone, which is associated with a more rapid spread of a message through social networks. The combination of these elements can heighten the risk of investors being exposed to and acting on the financial advice provided by finfluencers, regardless of the quality of that advice.

Our survey data shows that retail investors believe that finfluencers are generally motivated by self-interest. Despite this skeptical attitude, a sizable portion of investors believe that the finfluencers they follow are trustworthy. Increased trust in finfluencers could put investors at risk, particularly if the financial recommendations provided are of low quality.

Our experiment goes a step further by showing that finfluencer recommendations cause retail investors to make certain trading decisions. This observation is especially relevant given the dramatic increase in size of the retail investor population in recent years.[34] While finfluencer-investor relationships are not inherently harmful, our experiment demonstrates a clear capacity for finfluencer content to influence investor behaviour. Once again, this influence could diminish retail investor well-being—especially if the advice is of poor quality.

This research provides evidence to support the use of interventions to mitigate the persuasive effects of social media content on investor behaviour—disclosures, prebunking, and inoculation. In practice, these interventions could be delivered at scale by authorities through advertising placement on social media platforms. Given our findings, the delivery of these interventions to investors through the same social media platforms that they use may be both feasible and effective at protecting investors.

In sum, this research demonstrates that social media finfluencers have considerable capacity to influence retail investors’ decision making. Retail investors—especially less sophisticated retail investors—face certain risks with respect to the quality of information or advice accessed through social media. These findings reaffirm the importance of the continuance of regulatory oversight to ensure that finfluencer content is not harming retail investors.

In Canada, key guidance regarding finfluencer actions include:[35]

- Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA) Staff Notice 31-325 Marketing Practices of Portfolio Managers (July 2011)[36], which reminds market intermediaries (registered firms) to consider compliance and supervision in the use of social media for business purposes.

- CSA Staff Notice 33-321 Cyber Security and Social Media (October 2017)[37], which provided guidance on social media practices.

- CSA Staff Notice 51-356 Problematic Promotional Activities by Issuers (November 2018)[38], which cautions issuers against promotional activities that may artificially increase an issuer’s share price and trading volume or mislead investors.

- CSA and Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada (IIROC, a predecessor of the Canadian Investment Regulatory Organization (CIRO)) Staff Notice 21-330 Guidance for Crypto-Trading Platforms: Requirements relating to Advertising, Marketing and Social Media Use (September 2021)[39], which addresses deceptive advertising practices by crypto asset trading platforms, or other third parties acting on their behalf, that may have been contrary to investor protection or the public interest.

- OSC Staff Notice 33-755 Summary Report for Dealers, Advisors and Investment Fund Managers (July 2023)[40], which describes the continued adoption of digitized marketing practices of registrants that engage the services of third parties to assist them in establishing a digital presence in an effort to promote the firm’s products and services.

In light of the amplified impact that ‘finfluencers’ have on retail investors, authorities could consider more measures to directly address these concerns, including the implementation of behavioural science-based approaches to educational initiatives.

[34] Lush, M., Fontes, A., Zhu, M., Valdes, O., & Mottola, G. (2021). Investing 2020: New accounts and the people who opened them. Consumer Insights: Money & Investing.

[35] International Organization of Securities Commissions (2024). Finfluencers. https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD775.pdf

[36] Canadian Securities Administrators (2011). CSA Staff Notice 31-325: Marketing Practices of Portfolio Managers.

[37] Canadian Securities Administrators (2017). CSA Staff Notice 33-321 Cyber Security and Social Media.

[38] Canadian Securities Administrators (2018). CSA Staff Notice 51-356 Problematic Promotional Activities by Issuers.

[39] Canadian Securities Administrators, Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada (2021). CSA and IIROC Staff Notice 21-330 Guidance for Crypto-Trading Platforms: Requirements relating to Advertising, Marketing and Social Media Use.

[40] Ontario Securities Commission. (2023). OSC Staff Notice 33-755 Summary Report for Dealers, Advisors and Investment Fund Managers.

Authors & References

Authors

Ontario Securities Commission:

Matthew Kan

Senior Advisor, Behavioural Insights

[email protected]

Patrick Di Fonzo

Senior Advisor, Behavioural Insights

[email protected]

Marian Passmore

Senior Legal Counsel, Investor Office

[email protected]

Meera Paleja

Program Head, Behavioural Insights

[email protected]

Kevin Fine

Senior Vice President, Thought Leadership

[email protected]

The Decision Lab:

Turney McKee

Director

[email protected]

Jerónimo Muñoz Castillo Kanahuati

Consultant

Jestine Cabiles

Senior Research Analyst

Catalina Enestrom

Research Doctoral Fellow

Balaji, M. S., Jiang, Y., & Jha, S. (2021). Nanoinfluencer marketing: How message features affect credibility and behavioral intentions. Journal of Business Research, 136, 293-304.

Barber, B. M., & Odean, T. (2000). Trading is hazardous to your wealth: The common stock investment performance of individual investors. Journal of Finance, 55(2), 773-806.

Bode, L., & Vraga, E. K. (2015). In related news, that was wrong: The correction of misinformation through related stories functionality in social media. Journal of Communication, 65(4), 619-638.

Breves, P., Amrehn, J., Heidenreich, A., Liebers, N., & Schramm, H. (2021). Blind trust? The importance and interplay of parasocial relationships and advertising disclosures in explaining influencers’ persuasive effects on their followers. International Journal of Advertising, 40(7), 1209-1229.

Canadian Securities Administrators (2011). CSA Staff Notice 31-325: Marketing Practices of Portfolio Managers.

Canadian Securities Administrators (2017). CSA Staff Notice 33-321 Cyber Security and Social Media.

Canadian Securities Administrators (2018). CSA Staff Notice 51-356 Problematic Promotional Activities by Issuers.

Canadian Securities Administrators, Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada (2021). CSA and IIROC Staff Notice 21-330 Guidance for Crypto-Trading Platforms: Requirements relating to Advertising, Marketing and Social Media Use.

Canadian Securities Administrators (2024), 2024 CSA Investor Index.

Cialdini, R. B., & Cialdini, R. B. (2007). Influence: The psychology of persuasion (Vol. 55, p. 339). New York: Collins.

Clayton, K., Blair, S., Busam, J. A., Forstner, S., Glance, J., Green, G., ... & Nyhan, B. (2020). Real solutions for fake news? Measuring the effectiveness of general warnings and fact-check tags in reducing belief in false stories on social media. Political behavior, 42, 1073-1095.

Cook, J., Ellerton, P., & Kinkead, D. (2018). Deconstructing climate misinformation to identify reasoning errors. Environmental Research Letters, 13(2), 024018.

Cook, J., Lewandowsky, S., & Ecker, U. K. (2017). Neutralizing misinformation through inoculation: Exposing misleading argumentation techniques reduces their influence. PloS one, 12(5), e0175799.

Ecker, U. K., Lewandowsky, S., Cook, J., Schmid, P., Fazio, L. K., Brashier, N., ... & Amazeen, M. A. (2022). The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1(1), 13-29.

Fernandes, D., Lynch Jr, J. G., & Netemeyer, R. G. (2014). Financial literacy, financial education, and downstream financial behaviors. Management science, 60(8), 1861-1883.

Hayes, J. L., Golan, G., Britt, B., & Applequist, J. (2020). How advertising relevance and consumer–Brand relationship strength limit disclosure effects of native ads on Twitter. International Journal of Advertising, 39(1), 131-165.

Hornik, J., Satchi, R. S., Cesareo, L., & Pastore, A. (2015). Information dissemination via electronic word-of-mouth: Good news travels fast, bad news travels faster!. Computers in Human Behavior, 45, 273-280.

International Organization of Securities Commissions (2024). Finfluencers. https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD775.pdf

Kay, S., Mulcahy, R., & Parkinson, J. (2020). When less is more: the impact of macro and micro social media influencers’ disclosure. Journal of marketing management, 36(3-4), 248-278.

Lush, M., Fontes, A., Zhu, M., Valdes, O., & Mottola, G. (2021). Investing 2020: New accounts and the people who opened them. Consumer Insights: Money & Investing.

Mena, P. (2020). Cleaning up social media: The effect of warning labels on likelihood of sharing false news on Facebook. Policy & internet, 12(2), 165-183.

Meyer, E. A., Sandner, P., Cloutier, B., & Welpe, I. M. (2023). High on Bitcoin: Evidence of emotional contagion in the YouTube crypto influencer space. Journal of Business Research, 164, 113850.

Nekmat, E. (2020). Nudge effect of fact-check alerts: Source influence and media skepticism on sharing of news misinformation in social media. Social Media+ Society, 6(1), 2056305119897322.

Ontario Securities Commission. (2023). OSC Staff Notice 33-755 Summary Report for Dealers, Advisors and Investment Fund Managers.

Pennycook, G., Epstein, Z., Mosleh, M., Arechar, A. A., Eckles, D., & Rand, D. G. (2021). Shifting attention to accuracy can reduce misinformation online. Nature, 592(7855), 590-595.

Rickard, M. (2023, July 10). Categorization and Classification with LLMs. Matt Rickard. https://blog.matt-rickard.com/p/categorization-and-classification

Sah, S., Malaviya, P., & Thompson, D. (2018). Conflict of interest disclosure as an expertise cue: Differential effects due to automatic versus deliberative processing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 147, 127-146.

Sesar, V., Martinčević, I., & Boguszewicz-Kreft, M. (2022). Relationship between advertising disclosure, influencer credibility and purchase intention. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(7), 276.

She, J., & Zhang, T. (2019). The impact of headline features on the attraction of online financial articles. International Journal of Web Information Systems, 15(5), 510-534.

Tsugawa, S., & Ohsaki, H. (2015, November). Negative messages spread rapidly and widely on social media. In Proceedings of the 2015 ACM on conference on online social networks (pp. 151-160).

Van der Linden, S., Leiserowitz, A., Rosenthal, S., & Maibach, E. (2017). Inoculating the public against misinformation about climate change. Global challenges, 1(2), 1600008.

Wang, Y., Leon, P. G., Scott, K., Chen, X., Acquisti, A., & Cranor, L. F. (2013, May). Privacy nudges for social media: an exploratory Facebook study. In Proceedings of the 22nd international conference on world wide web (pp. 763-770).

WealthRocket. (2023, July 27). Half of Canadians Turn to Family and Friends First for Financial Advice, Banks a Close Second: WealthRocket Survey. Newswire.ca. https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/half-of-canadians-turn-to-family-and-friends-first-for-financial-advice-banks-a-close-second-wealthrocket-survey-839928927.html