Proposed amendments to final adopted Companion Policy 24-102CP to National Instrument 24-102 Clearing Agency Requirements

Proposed amendments to final adopted Companion Policy 24-102CP to National Instrument 24-102 Clearing Agency Requirements

[Editor's Note: For a full discussion of the Proposed Amendments to Companion Policy 24-102CP, please refer to Volume 38, Supplement 5 of the OSC Bulletin, published on December 3, 2015.]

PROPOSED AMENDMENTS TO FINAL ADOPTED COMPANION POLICY 24-102CP TO NATIONAL INSTRUMENT 24-102 CLEARING AGENCY REQUIREMENTS

Companion Policy 24-102CP is amended by inserting in Annex I the following immediately after Box 2.2:

"-- PFMI Principle 3: Framework for the comprehensive management of risks

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Box 3.1: Joint Supplementary Guidance -- Recovery Plans

Context

In 2012, to enhance the safety and efficiency of payment, clearing and settlement systems, the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (CPMI-IOSCO) released a set of international risk-management standards for FMIs, known as the Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures (PFMIs). The PFMIs provide standards regarding FMI recovery planning and orderly wind-down, which were adopted by the Bank of Canada as Standard 24 of the Bank's Risk-Management Standards for Designated FMIs and by the CSA as part of National Instrument 24-102.{1},{2} The Bank's Standard 24 is described as follows:

An FMI is expected to identify scenarios that may potentially prevent it from being able to provide its critical operations and services as a going concern and assess the effectiveness of a full range of options for recovery or orderly wind-down. This entails preparing appropriate plans for its recovery or orderly wind-down based on the results of that assessment.

In October 2014, the CPMI-IOSCO released its report, "Recovery of Financial Market Infrastructures" (the Recovery Report), providing additional guidance specific to the recovery of FMIs.{3} The Recovery Report explains the required structure and components of an FMI recovery plan and provides guidance on FMI critical services and recovery tools at a level sufficient to accommodate possible differences in the legal and institutional environments of each jurisdiction.

For the purpose of this guidance, FMI recovery is defined as the set of actions that an FMI can take, consistent with its rules, procedures and other ex ante contractual agreements, to address any uncovered loss, liquidity shortfall or capital inadequacy, whether arising from participant default or other causes (such as business, operational or other structural weakness), including actions to replenish any depleted pre-funded financial resources and liquidity arrangements, as necessary, to maintain the FMI's viability as a going concern and the continued provision of critical services.{4},{5}

Recovery planning is not intended as a substitute for robust day-to-day risk management. Rather, it serves to extend and strengthen an FMI's risk-management framework, enhancing the resilience of the FMI and bolstering confidence in the FMI's ability to function effectively even under extreme but plausible market conditions and operating environments,

Key Components of Recovery Plans

Overview of existing risk-management and legal structures

As part of their recovery plans, FMIs should include overviews of their legal entity structure and capital structure to provide context for stress scenarios and recovery activities.

FMIs should also include an overview of their existing risk-management frameworks-i.e., their pre-recovery risk-management activities. As part of this overview, and to determine the relevant point(s) where standard risk-management frameworks are exhausted, FMIs should identify all the material risks they are exposed to and explain how they use their existing risk-management tools to manage these risks to a high degree of confidence.

Critical services{6}

In their recovery plans, FMIs should identify, in consultation with Canadian authorities and stakeholders, the services they provide that are critical to the smooth functioning of the markets that they serve and to the maintenance of financial stability. FMIs may find it useful to consider the degree of substitutability and interconnectedness of each of these critical services, specifically

• The degree of criticality of an FMI's service is likely to be high if there are no, or only a small number of, alternative service providers. Factors related to the substitutability of a service could include (i) the size of a service's market share, (ii) the existence of alternative providers that have the capacity to absorb the number of customers and transactions the FMI maintains, and (iii) the FMI participants' capability to transfer positions to the alternative provider(s).

• The degree of criticality of an FMI's service may be high if the service is significantly interconnected with other market participants, both in terms of breadth and depth, thereby increasing the likelihood of contagion if the service were to be discontinued. Potential factors to consider when determining an FMI's interconnectedness are (i) what services it provides to other entities and (ii) which of those services are critical for other entities to function.

Stress scenarios{7}

In their recovery plans, FMIs should identify scenarios that may prevent them from being able to provide their critical services as a going concern. Stress scenarios should be focused on the risks an FMI faces from its payment, clearing and settlement activity. An FMI should then consider stress scenarios that cause financial stress in excess of the capacity of its existing risk controls, thereby pushing the FMI into recovery. An FMI should organize stress scenarios by the types of risk it faces; for each stress scenario, the FMI should clearly explain the following:

• the assumptions regarding market conditions and the state of the FMI within the stress scenario, accounting for the differences that may exist depending on whether the stress scenario is systemic or idiosyncratic;

• the estimated impact of a stress scenario on the FMI, its participants, participants' clients and other stakeholders; and

• the extent to which an FMI's existing pre-recovery risk-management tools are insufficient to withstand the impacts of realized risks in a recovery stress scenario and the value of the loss and/or of the negative shock required to generate a gap between existing risk-management tools and the losses associated with the realized risks.

Triggers for recovery

For each stress scenario, FMIs should identify the triggers that would move them from their pre-recovery risk-management activities (e.g., those found in a CCP's default waterfall) to recovery. These triggers should be both qualified (i.e., outlined) and, where relevant, quantified to demonstrate a point at which recovery plans will be implemented without ambiguity or delay.

While the boundary between pre-recovery risk-management activities and recovery can be clear (for example, when pre-funded resources are fully depleted), judgment may be needed in some cases. When this boundary is not clear, FMIs should lay out in their recovery plans how they will make decisions.{8} This includes detailing in advance their communication plans, as well as the escalation process associated with their decision-making procedures. They should also specify the decision-makers responsible for each step of the escalation process to ensure that there is adequate time for recovery tools to be implemented if required.

More generally, it is important to identify and place the triggers for recovery early enough in a stress scenario to allow for sufficient time to implement recovery tools. Triggers placed too late in a scenario will impede the effective rollout of these tools and hamper recovery efforts. Overall, in determining the moment when recovery should commence, and especially where there is uncertainty around this juncture, an FMI should be prudent in its actions and err on the side of caution.

Selection and Implementation of Recovery Tools{9}

A comprehensive plan for recovery

The success of a recovery plan relies on a comprehensive set of tools that can be effectively implemented during recovery. The applicability of these tools and their contribution to recovery varies by system, stress event and the order in which they are applied.

A robust recovery plan relies on a range of tools to form an adequate response to realized risks. Canadian authorities will provide feedback on the comprehensiveness of selected recovery tools when reviewing an FMI's complete recovery plan.

Characteristics of recovery tools

In providing this guidance, Canadian authorities used a broad set of criteria (described below), including those from the CPMI-IOSCO Recovery Report, to determine the characteristics of effective recovery tools.{10} FMIs should aim for consistency with these criteria in the selection and application of tools. In this context, recovery tools should be

• Reliable and timely in their application and have a strong legal and regulatory basis. This includes the need for FMIs to mitigate the risk that a participant may be unable or unwilling to meet a call for financial resources in a timely manner, or at all (i.e., performance risk), and to ensure that all recovery activities have a strong legal and regulatory basis.

• Measurable, manageable and controllable to ensure that they can be applied effectively while keeping in mind the objective of minimizing their negative effects on participants, , and the broader financial system. To this end, using tools that have predictable and capped participant exposure provides better certainty of a tool's impact on FMI participants and its contribution to recovery. Fairness in the allocation of uncovered losses and shortfalls, and the capacity to manage the associated costs, should also be considered.

• Transparent to participants: this should include a predefined description of each recovery tool, its purpose and the responsibilities and procedures of participants and the FMIs subject to the recovery tool's application to effectively manage participants' expectations. Transparency also mitigates performance risk by detailing the obligations and procedures of FMIs and participants beforehand to support the timely and effective rollout of recovery tools.

• Designed to create appropriate incentives for sound risk management and encourage voluntary participation in recovery to the greatest extent possible. This includes distributing post-recovery proceeds to participants that supported the FMI through the recovery process.

Systemic stability

Certain tools may have serious consequences for participants and for the stability of financial markets more generally. FMIs should use prudence and judgment in the selection of appropriate tools. Canadian authorities are of the view that FMIs should avoid uncapped, unpredictable or ill-defined participant exposures, which could create uncertainty and disincentives to participate in an FMI. Participants' ability to predict and manage their exposures to recovery tools is important, both for their own stability and for the stability of the indirect participants of an FMI.

In assessing FMI recovery plans, Canadian authorities are concerned with the possibility of systemic disruptions from the use of certain tools or tools that pose unquantifiable risks to participants. When selecting recovery tools, FMIs should keep in mind the objective of minimizing their negative impacts on participants, the FMI and the broader financial system.

Recommended recovery tools

This section outlines recommended recovery tools for use in FMI recovery plans. Not all tools are applicable for the different types of FMIs (e.g., a payment system versus a central counterparty). Each FMI should use discretion when selecting the most appropriate tools for its recovery plans, consistent with the considerations discussed above.

• Cash calls

Cash calls are recommended for recovery plans if they are capped and limited to a maximum number of rounds established in advance. The cap (on participant exposure) should be linked to each participant's risk-weighted level of FMI activity.

By providing predictable exposures pro-rated to a participant's risk-weighted level of activity, FMIs create incentives for better risk management on the part of participants, while giving the FMI greater certainty over the amount of resources that can be made available during recovery.

Since cash calls rely on contingent resources held by FMI participants, there is a risk that they may not be honoured, reducing their effectiveness as a recovery tool. The management of participants' expectations, especially placing clear limits on participant exposure, can mitigate this concern.

Cash calls can be designed in multiple ways to structure incentives, vary their impacts on participants and respond to different stress scenarios. When designing cash calls, FMIs should, to the greatest extent possible, seek to minimize the negative consequences of the tool's use.

• Variation margin gains haircutting (VMGH)

VMGH is recommended for recovery plans if its use is limited to a maximum number of rounds that are predefined by the FMI.

VMGH relies on participant resources posted at the FMI as variation margin (VM). Where the price movements of underlying instruments create sufficient VM gains for use in recovery, VMGH provides an FMI with a reliable and timely source of financial resources without the performance risk that is associated with tools reliant on resources held by participants.

VMGH assigns losses and shortfalls only to participants with net position gains; as a result, the pro rata financial burden is higher for these participants. The negative effects of VMGH can also be compounded for participants who rely on variation margin gains to honour obligations outside the FMI.

Participant exposure under VMGH can be measured with reasonable confidence since it is tied to the level of risk held in the VM fund and the potential for gains. By specifying the maximum number of rounds to which VMGH can be applied, an FMI will limit this exposure, providing better predictability of the tool's impact.

• Voluntary contract allocation

To recover from an unmatched book caused by a participant default, a CCP can use its powers to allocate unmatched contracts.{11} In the context of recovery, contract allocation should only be applied on a voluntary basis. Voluntary contract allocation (e.g., by auction) addresses unmatched positions while taking participant welfare into account since only participants who are willing to take on positions will participate.

The reliance on a voluntary process, such as an auction, introduces the risk that not all positions will be matched or that the auction process is not carried out in a timely manner. Defining the responsibilities and procedures for voluntary contract allocation (e.g., the auction rules) in advance will mitigate this risk and increase the reliability of the tool. To ensure that there is adequate participation in an auction process, FMIs should create incentives for participants to take on unmatched positions. FMIs may also wish to consider expanding the auction beyond direct participants to increase the chances that all positions will be matched.

• Voluntary contract tear-up

Since eliminating positions can help re-establish a matched book, Canadian authorities view contract tear-up as a potentially effective tool for FMI recovery. However, to the extent that the termination of an incomplete trade represents a disruption of a critical FMI service (albeit on a limited and intended basis), it can be too invasive to apply. Where contract tear-up is included in a recovery plan, FMIs should keep this in mind and perform tear-up only on a voluntary basis. To this end, FMIs may want to consider using incentives to encourage voluntary tear-up during recovery.

To the extent that a voluntary contract tear-up still disrupts critical FMI services, it can produce disincentives to participate in an FMI. There should be a strong legal basis for the relevant processes and procedures when a voluntary contract tear-up is included in a recovery plan. This will help to manage participant expectations for this tool and ensure that confidence in the FMI is maintained.

Other tools available for FMI recovery include standing third-party liquidity lines, contractual liquidity arrangements with participants, insurance against financial loss, increased contributions to pre-funded resources, and use of an FMI's own capital beyond the default waterfall. These and other tools are often already found in the pre-recovery risk-management frameworks of FMIs; nonetheless, Canadian authorities encourage their use for recovery as well, provided they are in keeping with the criteria for effective recovery tools as found in the Recovery Report and in this guidance.{12}

To the extent that the costs of recovery are shared less equally under some tools (e.g., VMGH), if it is financially feasible, FMIs could consider post-recovery actions to restore fairness where participants have been disproportionately affected. Such actions may include the repayment of participant contributions used to address liquidity shortfalls and other instruments that aim to redistribute the burden of losses allocated during recovery. It is important to note that these actions in the post-recovery period should not impair the financial viability of the FMI as a going concern.

Tools not recommended for recovery plans

Due to their uncertain and potentially negative effects on the broader financial system, Canadian authorities do not encourage the inclusion of uncapped and unlimited rounds of cash calls, unlimited rounds of VMGH, involuntary (forced) contract allocation, involuntary (forced) contract tear-up, and the use of non-defaulting participants' initial margin in FMI recovery plans. These could potentially be used by a resolution authority but would need to be carefully assessed against their potential impact on participants and the stability of the broader financial system.

While these tools can potentially address liquidity or capital shortfalls, it could be to the detriment of the broader financial system and the viability of the FMI. Uncapped and unlimited cash calls and unlimited rounds of VMGH can create ambiguous participant exposures, while exposures to involuntary contract allocation and tear-up activities can be difficult to manage, measure and control, even when they offer incentives to assist with recovery.

Where FMIs believe that these tools should be included in a recovery plan, the tools must be carefully considered and accompanied by a strong rationale for their use. Canadian authorities will provide feedback on the suitability of any such tools as part of their review of a recovery plan.

Recovery from non-default-related losses and structural weaknesses

Consistent with a defaulter-pays principle, an FMI should rely on FMI-funded resources to address recovery from non-default-related losses (i.e., operational and business losses on the part of an FMI), including losses arising from structural weakness.{13} To this end, FMIs should examine ways to increase the loss absorbency between the FMI's pre-recovery risk-management activities and participant-funded resources (e.g., by using FMI-funded insurance against operational risks).

Structural weakness can be an impediment to the effective rollout of recovery tools and may itself result in non-default-related losses that are a trigger for recovery. An FMI recovery plan should include a process detailing how to promptly identify, evaluate and address the sources of underlying structural weakness on a continuous basis (e.g., unprofitable business lines, investment losses) and the tools available to address them within a concrete time frame.

The use of participant-funded resources to recover from non-default-related losses can lessen incentives for robust risk management within an FMI and provide disincentives to participate. If, despite these concerns, participants consider it in their interest to keep the FMI as a going concern, an FMI and its participants may agree to include a certain amount of participant-funded recovery tools to address some non-default-related losses. Under these circumstances, the FMI should clearly explain under what conditions participant resources would be used and how costs would be distributed.

Defining full allocation of uncovered losses and liquidity shortfalls

Principles 4 (credit risk){14} and 7 (liquidity risk){15} of the PFMIs require that FMIs should specify rules and procedures to fully allocate both uncovered losses and liquidity shortfalls caused by stress events, such as participant default. Rules to fully allocate all uncovered credit losses and liquidity shortfalls may be implemented either as part of recovery and/or resolution. To be consistent with this requirement, Canadian FMIs should consider various stress scenarios and have rules and procedures that allow them to fully allocate any loss or liquidity shortfall arising from those stress scenarios. For additional guidance on stress scenarios and triggers for recovery, see the Recovery Report, Sections 2.4.5 and 2.4.6 and page 3 of this document.

Legal consideration for full allocation

An FMI's rules for allocating losses and liquidity shortfalls should be supported by relevant laws and regulations. There should be a high level of certainty that rules and procedures to fully allocate all uncovered losses and liquidity shortfalls are enforceable and will not be voided, reversed or stayed.{16} This requires that Canadian FMIs design their recovery tools in compliance with Canadian laws. For example, if the FMI's loss-allocation rules involve a guarantee, Canadian law generally requires that the guaranteed amount be determinable and preferably capped by a fixed amount.{17}

FMIs should consider whether it is appropriate to involve indirect participants that do not benefit from a customer-protection regime in the allocation of losses and shortfalls during recovery. Such loss or shortfall allocation arrangement should have a strong legal and regulatory basis and involve consultation with indirect participants to ensure that all relevant concerns are taken into account.

Overall, FMIs are responsible for seeking appropriate legal advice on how their recovery tools can be designed and for ensuring that all recovery tools and activities are in compliance with the relevant laws and regulations.

Additional Considerations in Recovery Planning

Transparency and coherence{18}

An FMI should ensure that its recovery plan is coherent and transparent to all relevant levels of management within the FMI, as well as to its regulators and overseers. To do so, a recovery plan should

• contain information at the appropriate level and detail; and

• be sufficiently coherent to relevant parties within the FMI, as well as to the regulators and overseers of the FMI, to effectively support the implementation of the recovery tools.

An FMI should ensure that the assumptions, preconditions, key dependencies and decision-making processes in a recovery plan are transparent and clearly identified.

Relevance and flexibility{19}

An FMI's recovery plan should thoroughly cover the information and actions relevant to extreme but plausible market conditions and other situations that would call for the use of recovery tools. An FMI should take into account the following elements when developing its recovery plan:

• the nature, size and complexity of its operations;

• its interconnectedness with other entities;

• operational functions, processes and/or infrastructure that may affect the FMI's ability to implement its recovery plan; and

• any upcoming regulatory reforms that may have the potential to affect the recovery plan.

Recovery plans should be sufficiently flexible to address a range of FMI-specific and market-wide stress events. Recovery plans should also be structured and written at a level that enables the FMI's management to assess the recovery scenario and initiate appropriate recovery procedures. As part of this expectation, the recovery plan should demonstrate that senior management has assessed the potential two-way interaction between recovery tools and the FMI's business model, legal entity structure, and business and risk-management practices.

Implementation{20}

An FMI should have credible and operationally feasible approaches to recovery planning in place and be able to act upon them in a timely manner, under both idiosyncratic and market-wide stress scenarios. To this end, recovery plans should describe

• potential impediments to implementing recovery tools effectively and strategies to address them; and

• the impact of a major operational disruption.{21}

This information is important to strengthen a recovery plan's resilience to shocks and ensure that the recovery tools are actionable.

A recovery plan should also include an escalation process and the associated communication procedures that an FMI would take in a recovery situation. Such a process should define the associated timelines, objectives and key messages of each communication step, as well as the decision-makers who are responsible for it.

Consulting Canadian authorities when taking recovery actions

While the responsibility for implementing the recovery plan rests with the FMI, Canadian authorities consider it critical to be informed when an FMI triggers its recovery plan and before the implementation of recovery tools and other recovery actions. This includes the authorities responsible for the regulation, supervision and oversight of the FMI, as well as any authorities who would be responsible for the FMI if it were to be put into resolution.

Canadian FMIs should consult Canadian authorities before implementing any and all recovery tools and actions to ensure that decisions take into account potential financial stability implications and other relevant public interest considerations. This action should occur early on and should be explicitly identified in the escalation process of a recovery plan. Acknowledging the speed at which an FMI may enter recovery, FMIs are encouraged to develop formal communications protocols with authorities in the event that recovery is triggered and immediate action is required.

Review of Recovery Plan{22}

An FMI should include in its recovery plan a robust assessment of the recovery tools presented and detail the key factors that may affect their implementation. It should recognize that, while some recovery tools may be effective in returning the FMI to viability, these tools may not have a desirable effect on its participants or the broader financial system.

A framework for testing the recovery plan (for example, through scenario exercises, periodic simulations, back-testing and other mechanisms) should be presented either in the plan itself or linked to a separate document. This impact assessment should include an analysis of the effect of implementing recovery tools on financial stability and other relevant public interest considerations.{23} Furthermore, an FMI should demonstrate that the appropriate business units and levels of management have assessed the potential consequences of recovery tools on FMI participants and entities linked to the FMI.

Annual review of recovery plan

An FMI should review and, if necessary, update its recovery plan on an annual basis. The recovery plan should be subject to approval by the FMI's Board of Directors.{24} Under the following circumstances, an FMI is expected to review its recovery plan more frequently:

• if there is a significant change to market conditions or to an FMI's business model, corporate structure, services provided, risk exposures or any other element of the firm that could have a relevant impact on the recovery plan;

• if an FMI encounters a severe stress situation that requires appropriate updates to the recovery plan to address the changes in the FMI's environment or lessons learned through the stress period; and

• if the Canadian authorities request that the FMI update the recovery plan to address specific concerns or for additional clarity.

Canadian authorities will also review and provide their views on an FMI's recovery plan before it comes into effect. This is to ensure that the plan is in line with the expectations of Canadian authorities.

Orderly Wind-Down Plan as Part of a Recovery Plan{25}

Canadian authorities expect FMIs to prepare, as part of their recovery plans, for the possibility of an orderly wind-down. However, developing an orderly wind-down plan may not be appropriate or operationally feasible for some critical services. In this instance, FMIs should consult with the relevant authorities on whether they can be exempted from this requirement.

Considerations when developing an orderly wind-down plan

An FMI should ensure that its orderly wind-down plan has a strong legal basis. This includes actions concerning the transfer of contracts and services, the transfer of cash and securities positions of an FMI, or the transfer of all or parts of the rights and obligations provided in a link arrangement to a new entity.

In developing orderly wind-down plans, an FMI should elaborate on

• the scenarios where an orderly wind-down is initiated, including the services considered for wind-down;

• the expected wind-down period for each scenario, including the timeline for when the wind-down process for critical services (if applicable) would be complete; and

• measures in place to port critical services to another FMI that is identified and assessed as operationally capable of continuing the services.

Disclosure of recovery and orderly wind-down plans

An FMI should disclose sufficient information regarding the effects of its recovery and orderly wind-down plans on FMI participants and stakeholders, including how they would be affected by (i) the allocation of uncovered losses and liquidity shortfalls and (ii) any measures the CCP would take to re-establish a matched book. In terms of disclosing the degree of discretion an FMI has in implementing recovery tools, an FMI should make it clear to FMI participants and all other stakeholders ahead of time that all recovery tools and orderly wind-down actions that an FMI can implement will only be employed after consulting with the relevant Canadian authorities.

Note that recovery and orderly wind-down plans need not be two separate documents; the orderly wind-down of critical services may be a part or subset of the recovery plan. Furthermore, Canadian FMIs may consider developing orderly wind-down plans for non-critical services in the context of recovery if winding down non-critical services could assist in or benefit the recovery of the FMI.

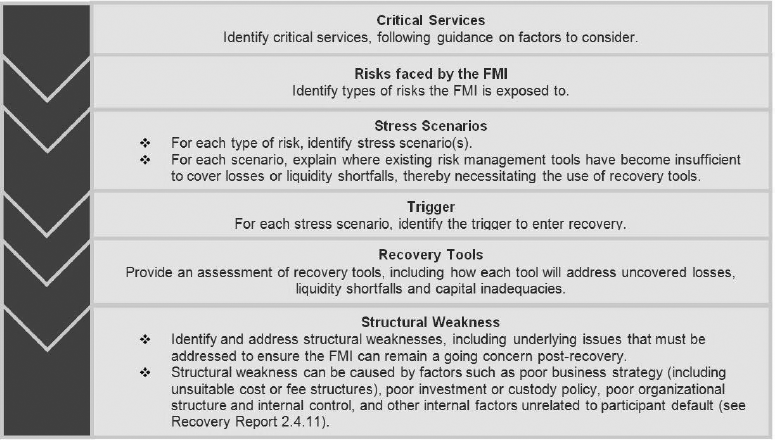

Annex: Guidelines on the Practical Aspects of FMI Recovery Plans

The following example provides suggestions on how an FMI recovery plan could be organized.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

{1} See key consideration 4 of PFMI Principle 3 and key consideration 3 of PFMI Principle 15 which are adopted in the Canadian Securities Administrators' (CSA) National Instrument 24-102 Clearing Agency Requirements, section 3.1.

{2} The Bank of Canada's Risk-Management Standards for Designated FMIs is available at http://www.bankofcanada.ca/core-functions/financial-system/bank-canada-risk-management-standards-designated-fmis/.

{3} Available at http://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d121.pdf.

{4} Recovery Report, Paragraph 1.1.1.

{5} For a precise definition of orderly wind-down, see the Recovery Report, Paragraph 2.2.2.

{6} Recovery Report, Paragraph 2.4.2-2.4.4.

{7} Recovery Report, Paragraph 2.4.5.

{8} Recovery Report, Paragraph 2.4.8.

{9} Recovery Report, Paragraph 2.3.6 - 2.3.7 and 2.5.6 and Paragraphs 3.4.1 - 3.4.7.

{10} Recovery Report, Paragraph 3.3.1.

{11} A "matched book" occurs when there is an equal distribution of assets and liabilities. In the context of a CCP, and at a simplified level, this refers to the matched positions that form the two sides of an active trade. A matched book must be maintained for the CCP to complete a trade. An unmatched book occurs when one participant defaults on its position in the trade, leaving the CCP unable to complete the transaction.

{12} Recovery Report, Paragraph 3.3.1.

{13} Structural weakness can be caused by factors such as poor business strategy, poor investment and custody policy, poor organizational structure, IM/IT-related obstacles, poor legal or regulatory risk frameworks, and other insufficient internal controls.

{14} Under key consideration 7 of PFMI Principle 4, an FMI should establish explicit rules and procedures that fully address any credit losses it may face as a result of any individual or combined default among its participants with respect to any of their obligations to the FMI.

{15} Under key consideration 10 of PFMI Principle 7, FMIs should establish rules and procedures that address unforeseen and potentially uncovered liquidity shortfalls and should aim to avoid unwinding, revoking or delaying the same-day settlement of payment obligations.

{16} CPMI-IOSCO Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures, Paragraph 3.1.10.

{17} The Bank Act, Section 414.1 and IIROC Rule 100.14 prohibit banks and securities dealers, respectively, from providing unlimited guarantees to an FMI or a financial institution.

{18} Recovery Report, Section 2.3.

{19} Recovery Report, Section 2.3.

{20} Recovery Report, Paragraph 2.3.9.

{21} This is also related to the FMI's backup and contingency planning, which are distinct from recovery plans.

{22} Recovery Report, Paragraph 2.3.8.

{23} This is in line with key consideration 1 of PFMI Principle 2 (Governance), which states that an FMI should have objectives that place a high priority on the safety and efficiency of the FMI and explicitly support financial stability and other relevant public interest considerations.

{24} Recovery Report, Paragraph 2.3.3.

{25} Recovery Report, Paragraph 2.2.2.